SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – No other lists have sent shockwaves across the country like the lists of President Rodrigo Duterte.

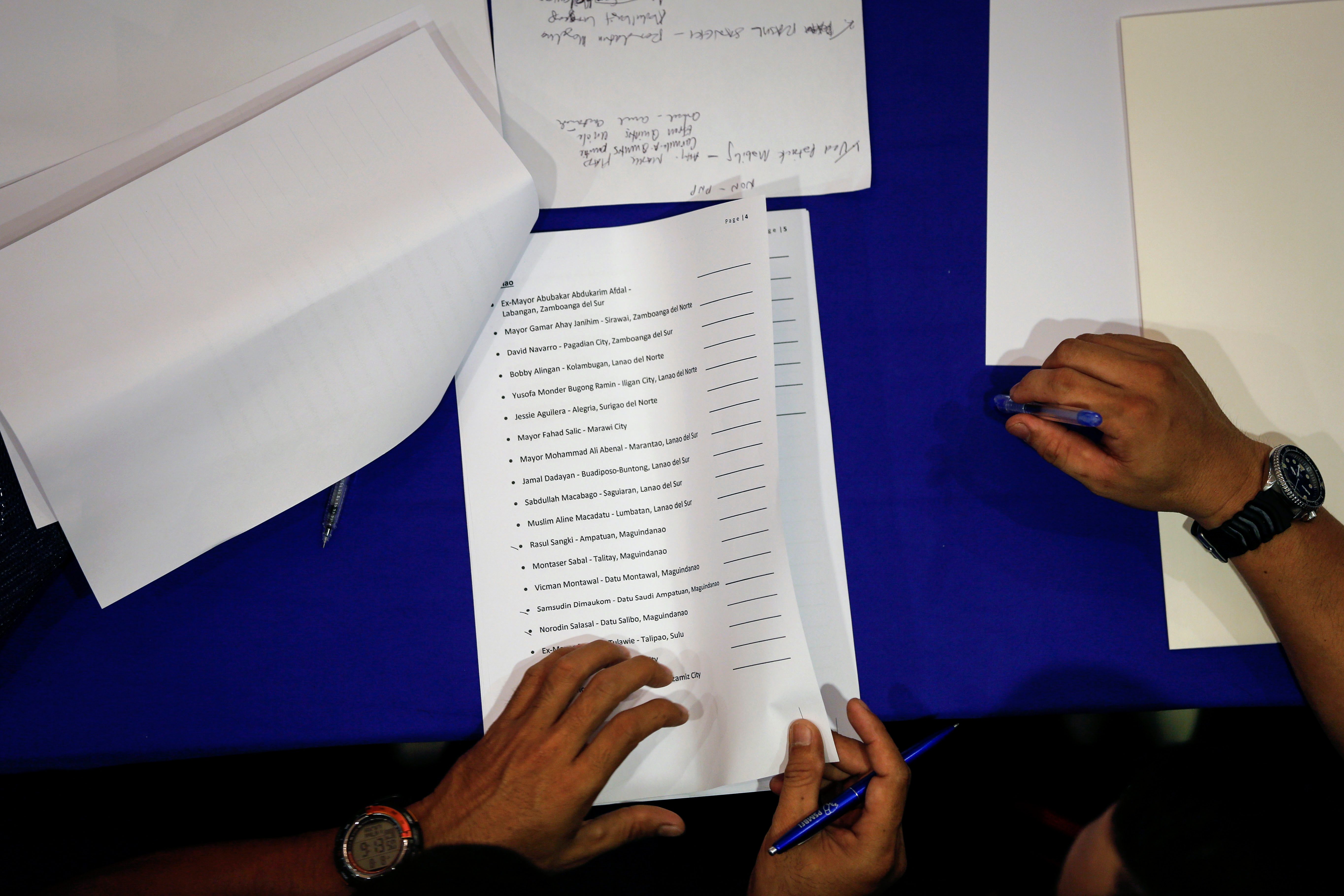

The latest list – containing 158 names of mayors, vice mayors, police, judges, and congressmen – now have everyone looking around their own towns or cities for who might be next on the list. Some out there may be waiting in dread.

Before that list, Duterte came out with the names of 3 top Chinese drug lords. His very first bombshell was a list of 5 police generals supposedly coddling drug traders.

Call it audacious, crazy, or dangerous, but naming names are part of Duterte’s anti-crime strategy. He’s done it before as Davao City mayor. Any Davaoeño will tell you that he used to announce names of criminals, drug pushers, and drug addicts during his weekly TV show. (READ: Dissecting, weighing Duterte’s anti-crime strategy)

He starts with a warning then starts looking into who are these people. That’s when the list will come out.

– Wendel Avisado, former Davao city administrator

In fact, all his recent moves in the name of his war on drugs mirror his tried and tested methods as mayor.

No doubt, in his mind, what was effective for Davao might just be successfully replicated on a national scale.

I talked to Wendel Avisado, who served as the City Administrator under Duterte from 2004 to 2010. Avisado is known to have practically run City Hall for the bureaucracy-allergic Duterte.

Duterte’s TV show, Gikan Sa Masa Para Sa Masa, began sometime in the 1990s, some years after he was first elected mayor in 1988, said Avisado.

It was principally a way for him to directly communicate with Davaoeños about policies, regulations, and the overall state of the city, with the help of a co-host.

It was also one way for citizens to directly reach Duterte. On the show, Duterte would read letters from citizens who wanted to air out complaints or concerns. He would right then and there try to address the issues raised by barking out orders to his staff who were of course tuned in to the show, even if it aired on a Sunday.

Here is a 2010 episode uploaded on YouTube:

When citizens complain

Criminality, peace and order were among (and still are) Duterte’s favorite conversation topics. On his show, he would often rant about kidnappings, car accidents, noisy karaoke, or rape incidents before thinking out loud about regulations he was considering in order to improve the situation.

It was the citizens’ complaints he received during his show that prompted him to think of naming suspicious persons.

“When the people started complaining so much about the drug proliferation, he said, ‘Okay, I’ll do something about it.’ He starts with a warning then starts looking into who are these people. That’s when the list will come out, then validate, then he makes the announcements that these are the people with a final warning,” related Avisado.

One Sunday in October 2001, Mayor Duterte announced the names of 500 people he said “could help the city in its fight against drugs.”

Asked by MindaNews Editor-in-Chief Carol Arguillas why he made the list public, Duterte had said, “I was appealing to the patriotism, the civic spirit I might rekindle in the minds, hearts of these people. [Also] to put them on guard, [that] we know something about you [so] you stop it. Second, the community must know.”

Back then, Duterte had packaged his warning as a call for help, though most people knew he was referring to drug suspects. But today, no one would mistake his threats and cursing as a plea to patriots.

“Alam mo, maski saan kayo magpunta aabangan ko kayo – maski wala na ako sa presidency, habang may baril ako,” Duterte said in the middle of naming the 158.

(You know, wherever you go, I will be waiting for you – even if I am no longer in the presidency, as long as I have a gun.)

‘Right to know’

But one thing remains from his TV show days, he still insists he is announcing names to fulfill his duty of informing the people of the drug problem.

“Ako’y nagsasalita po sa taong-bayan at malaman po ninyo ano ang katotohanan sa ating buhay dito sa Pilipinas,” he said in the same speech. (I am speaking to the people so you know the truth about our life here in the Philippines.)

He was reading a list from his program Gikan Sa Masa Para Sa Masa, warning them. After 2 or 3 weeks…patay na.

– Fr Amado Picardal, CASE

Back then, what were his intentions in reading out names? Avisado, like Duterte’s spokesmen today, say he does not seek the immediate arrest of those named, only that they come forward and explain why intelligence agencies have them on their watchlist.

“He wants to send the message that your names are in the list submitted to me so, to give you a chance, please go see the Chief of Police or me, or to the Mayor’s Office so that you can choose among the options available,” said Avisado.

And what were these options? Surrenderees could either check themselves into the city drug rehabilitation center for free or leave the city.

Avisado himself facilitated the endorsement of the named drug addicts to the rehabilitation center. In some cases where the addict is the breadwinner, their families would be given allowance by the city, said Avisado.

If the person named refused to go into rehab, he would have to leave the city or risk death – at the hands of whom, he might never know.

“The advise is, bakasyon na lang kayo para mapalayo kayo diyan (take a vacation so you are far from here). From the words of the mayor, ‘I can no longer protect you,’” said Avisado.

Duterte’s threat may have remained merely that if not for the fact that some people he named really did end up dead.

Out of the 500 people whose names he announced in October 2001, at least 4 were killed or found dead the following month, reported MindaNews. Months after, 17 more were killed.

Father Amado Picardal, a priest who documented extrajudicial killings in Davao City with his group Coalition Against Summary Executions (CASE), also said some of those in the list ended up dead under mysterious circumstances.

“[Duterte] was reading a list from his program Gikan Sa Masa Para Sa Masa, warning them. After 2 or 3 weeks, those being recognized, patay na (were dead),” he told Rappler.

That Duterte ordered these killings has never been proven, due to lack of evidence – even if his colorful threats very much indicate he would have been happy to have masterminded them.

But whether or not it was Duterte or his men who pulled the trigger or wielded the knife, it can’t be denied that his lists render those in them particularly vulnerable to attack.

Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno was keenly aware of this when she wrote to Duterte about the 7 judges in his list.

“Our judges may have been rendered vulnerable and veritable targets for any of those persons and groups who may consider judges as acceptable collateral damage in the ‘war on drugs,'” Sereno said.

But Duterte did not even address this concern in speeches he gave after. In fact, he only repeated his order that the named judges be stripped of the authority to carry firearms, making them even more helpless should they be attacked.

Could those who died in Davao also have been “collateral damage” in Duterte’s list-making? Do Duterte’s lists really speed up the slow justice system or do they only empower faceless vigilantes to take justice into their own hands?

‘Re-validated’ list?

Another hotly debated aspect of Duterte’s lists is their veracity. Where did he get the information? Were they validated by multiple sources? Did politics play a part in how the lists were formed?

Media outfits have been caught in a whirlwind of fact-checking, revealing a dead mayor, judge, and cop, a “legislator” who never was one, and many cases of incomplete and misspelled names.

Malacañang has so far not made any efforts to correct the list. In fact, to this day, Duterte is yet to release a complete text copy of his list. Media continue to rely on transcripts of his speech.

The official Malacañang transcript was typed up by transcribers who also relied only on their hearing and perhaps stock knowledge to spell the names. (How would they know that the “Ryan” referring to a Batangas mayor is actually spelled “Ryanh”?)

Duterte tells the public, in bits and pieces, how he got the information. In an August 9 press conference in Davao City, he said the names, at one point, surfaced from a computer – most likely a digital database of law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

“Kasi ‘pag dating sa akin, galing man ‘yan sa intelligence community. Collated ‘yan eh. Titingnan muna sa computer. ‘Ito noon pa.’ Tapos pagdating sa akin, re-evaluation again,” he said to media.

Every barangay has to submit a list of who are the notorious ones.

– Fr Amado Picardal, CASE

(It gets to me from the intelligence community. It’s collated information. They will check the computer first to check if his name has been there before. Then when it gets to me, there will be re-evaluation.)

Some of the names, he said, have been on the watchlists of intelligence agencies since 5 years ago, or during the previous administration, which explains the outdated information regarding some of the personalities.

But whether or not the person is dead or alive is beside the point, said Duterte.

“That means that, historically, he was playing with drugs,” he said.

The next day, still not over the criticisms of his “inaccurate” list, Duterte stormed, “So? Why should I exempt the dead?”

‘Combination’ of sources

For his old Davao lists, Duterte relied on a “combination” of sources including the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group, local government officials, local police, military, National Bureau of Investigation, and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, said Avisado.

Those days, Duterte would even make his own calls to check on certain areas or agencies.

“Pagka-ganyan ang problema, tatawagan niya, ‘O, kamusta diyan sa inyo, may problema ba? (When there is a problem, he will call, ‘How are you there? Are there problems?) Then people will start talking then he will start also validating,” said Avisado.

Duterte also listened to complaints from citizens, whether through his show or when they personally approached him.

Picardal, meanwhile, said Duterte relied on barangay captains for information.

“Every barangay has to submit a list of who are the notorious ones. I met some barangay leaders who said, ‘We have to submit the names, sino dito ang mga troublesome (of those who are troublesome in the area),” he said.

Avisado said Duterte’s revalidation of names always involved a “process.”

After getting a tip, he would have it revalidated by telling personnel, most often police, to visit the person’s neighborhood and ask around.

“They asked the people within the vicinity, or the person’s associates, those who know him. There were many ways. Barangay officials would also be consulted,” said Avisado.

Even then, there was no assurance that Duterte’s list was “100% accurate.”

For this reason, Duterte entertained surrenderees in his office and listened to them explain why their names should not have been on the list.

But Duterte has never gone on his TV show to retract a name or apologize for a wrong name, said Avisado.

This is because, as Duterte says to defend himself, he never said they were guilty of a crime.

Before announcing the 158 names, his preface was, “I’m reading now the [drug] personalities in the Philippines. It might be true. It might not.”

For Avisado, Duterte’s message is, “I’m not saying they’re involved but rather that their name surfaced in a series of intelligence gathering and precisely there’s a need for them to be informed about it.”

Then vs Now

The events surrounding Duterte’s current nationwide war on drugs mirror the events that surrounded his city-wide war on drugs.

Now, over 540,000 drug addicts have surrendered. Back then, in Davao, drug addicts also surrendered in droves, filling covered courts.

Some of those who surrendered were not even on Duterte’s list but stepped forward anyway and signed “commitment papers” that they would stop their illegal activities, said Avisado.

This is similar to the case of a Lanao del Sur mayor and former mayor who surrendered to the PNP two days before Duterte even announced his list of 158.

Duterte always warned his war would be “bloody” and this is reflected in the number of alleged drug suspects killed since he took his oath – 513 killed during anti-drug operations as of August 9, according to the Philippine National Police.

A list by the Philippine Daily Inquirer says the death toll is at 564 as of August 8 but their list includes summary killings, or killings by alleged hitmen not by police. (LOOK: War on drugs: While you were sleeping)

In the midst of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign in Davao City, there were casualties too. According to the Coalition Against Summary Executions, 1,424 died in the city from 1998 to 2015 at the hands of “death squads” and police during raids.

Duterte has said he is claiming responsibility for all the consequences of his lists. But the lists he is making now have more far-reaching consequences compared to his Davao City list. Now, he is naming government officials, not just petty criminals. He has even named foreigners – like the 3 Chinese drug lords, one of whom is thought to be out of the country, likely in China.

In fact, China has already responded to Duterte’s accusation that they are harboring drug lords.

Duterte’s lists have brought his war on drugs on a whole new level. Its enemies, the drug lords and protectors he so abhors, are no doubt planning their next move.

Can Duterte shield the innocent from the crossfire that could ensue? Can he keep up with his own war? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.