SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

The first (unfortunate) burden of any restaging is proving its relevance and justifying its reinventions. But luckily, the draw of The Crucible, Arthur Miller’s award-winning play, is its mutability. The Crucible dramatizes the crumbling of a community in Salem, Massachusetts between 1692-1693 due to accusations of witchcraft. In a 1996 essay for The New Yorker, Miller noted the play’s function as either a “warning” or “reminder,” depending on whether or not “a political coup appears imminent or a dictatorial regime had just been overthrown.” While the text was initially written in response to McCarthyism in 1950s America, Miller acknowledges that the central allegory makes its relevance an unlimited resource.

It’s easy to draw parallels between Ang Pag-Uusig, the Filipino translation of Miller’s text by Jerry Respeto, and Philippine history. When the production was first staged in 2017, the country was still struggling to walk without blowing up a political landmine. Only a year into Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency, the war on drugs had already claimed thousands of lives, martial law had been imposed in Marawi, and Ferdinand Marcos Sr. had been buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. In 2018, when the production was staged for a second time, the country was alive with the challenges of living in a post-truth world and the growing culture of impunity — connections between Cambridge Analytica and the 2016 elections were only starting to surface, rampant online disinformation made it difficult to separate truth from fallacy, and Rappler’s own license to operate was under threat of being revoked.

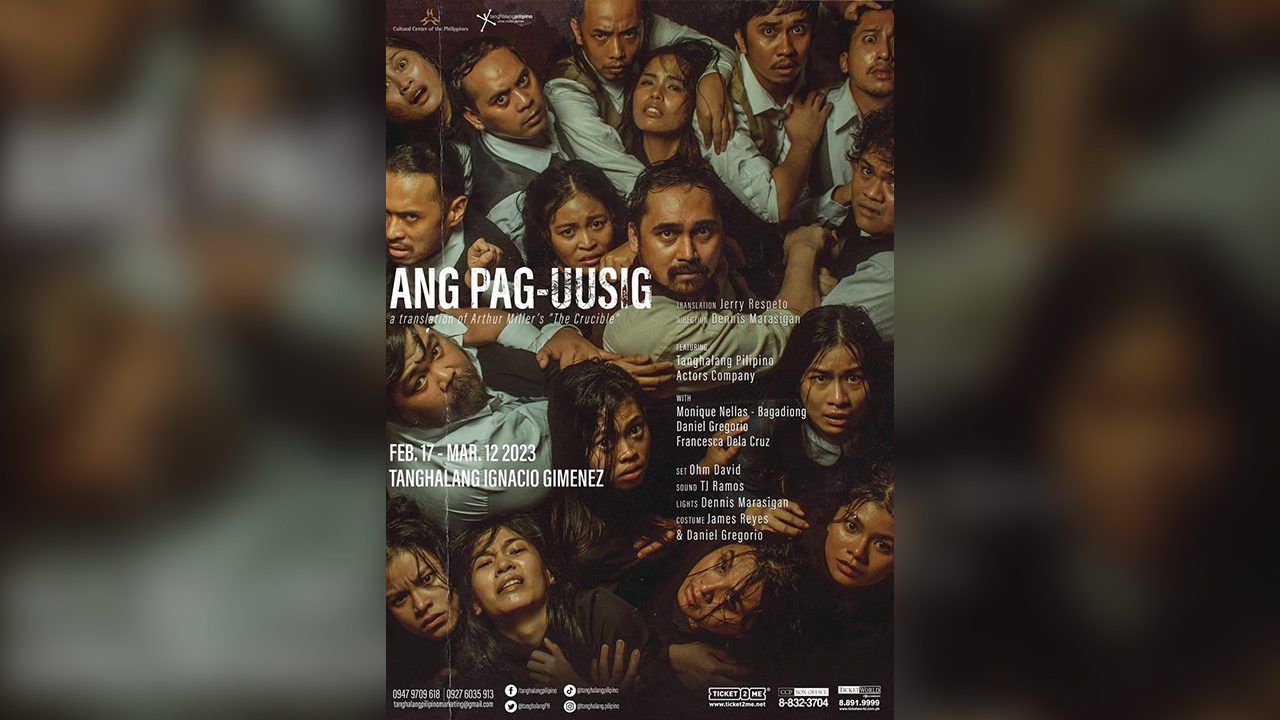

Now, Tanghalang Pilipino has opted to stage the production for a third time, five years later, after not only a global pandemic and one of the most divisive elections in our country’s history, but also a time when it is easiest to slip into moral panic due to economic depression and distrust in technology.

But what else can be gained from restaging a 70-year-old source text? What more does it have to say? Countless productions have opted to modernize the affair by setting it in the current milieu. Ivo van Hove’s Broadway staging in 2016 turned Salem into a classroom and changed the maids into schoolgirls, subsequently leaning into the supernatural. But director Dennis Marasigan opts to situate Ang Pag-uusig in 17th-century Salem, Massachusetts, under the assumption that the audience’s intelligence and the strength of Respeto’s translation will be sufficient in conveying the potency of the allegory.

In fact, Marasigan strips the production down to its barest bones. Ohm David creates a minimalist thrust stage using shipwreck-brown wooden panels, while Daniel Gregorio supplements the work of the late James Reyes by dressing the characters in clothing stripped of bright colors, seemingly dirtied and dulled from hard work in the fields and forests. Even the stage direction is sucked of any kinetic energy, and the ensemble — most of whom are made of members of the Tanghalang Pilipino’s Actor’s Company — remains stiff, their voices carrying, even if at times buckling under, the weight of rapid dialogue used to point fingers. The only noticeable movement is in the sound, the low thrums designed by TJ Ramos weaving in and out, becoming a source of discomfort and anticipated terror.

Such tension would typically be a detriment, especially considering that the actors’ bodies and faces are often obscured due to blocking. But much of this is purposeful in Ang Pag-uusig, as it forces the audience to coil under the mounting claustrophobia, unease, and frustration, all of which externalize the moral stasis of the story. Sudden movements in this puritanical society are seen as an invocation of the devil, an act of perjury, and a confession to complicity in witchcraft.

Marasigan’s artistic choices put the burden of nuance on his actors. But despite their talents, Act I is a strain to watch. Much of Respeto’s text is left unintelligible or thrown away due to the actors’ speech patterns, the mismatches in their characterizations, and acting styles detracting from the truth of the source text. A key loss is the racial and class component that forces Tituba, the Barbadian slave, into lying about witchcraft, which is the first domino that sets the inquisition into motion. Only when Marco Viaña’s world-weary John Proctor steps onstage does the play find any sort of grounding.

Act II and III pick up thanks to the generous work of Lhorvie Nuevo and Aggy Mago, who play John’s wife Elizabeth and their maid Mary Warren, respectively. Nuevo commands her household with quiet energy, her still manner reflecting the coldness of their marriage, while Mago is perfect as Mary Warren, embodying childlike charm and humor without sacrificing truth or emotional heft. Mary Warren’s loss of innocence and submission to fear is one of the production’s first casualties and an indication of the darkness to come.

The success and failure of Ang Pag-uusig hinges on the performance of Antonette Go, who, as Abigail Williams, is aptly described by writer Eljay Castro Deldoc as a “supernova.” In Act III, her emotions become a violent unspooling that liberates her at the cost of destroying the community, channeling traces of Isabelle Adjani in Andrzej Żuławski’s 1981 film Possession. While these moments of explosion will undoubtedly earn her praise, Go is at her most compelling in her quiet — when she is taking in information while taking care of Betty, whispering to John Proctor, or calculating her next move in the courtroom.

Go’s Abigail serves as the fulcrum of Ang Pag-Uusig because the burden of proof is on the accuser, and her imagination draws the lines that define who one should or shouldn’t believe. But layers of complexity are neutered, maybe even lost, as Go registers more as a vengeful adult woman than a scorned 17-year-old maid. Such detail is crucial in establishing the unequal power dynamics between John and Abigail.

Yes, the work still functions as an effective allegory for contemporary Philippine society and how it is ruined when the personal interest of the powerful few becomes a national concern. But in this decision not to drop in age, Abigail’s decisions come off as manipulative actions of a prototypical madwoman rather than a teenager lashing out without a full understanding of the consequences of her actions, an idea that is fleshed out more in the 1996 film than in the play.

What must be stated is that Ang Pag-Uusig encourages us to disbelieve the accusers — the women and children — but not those handing out the judgments and executions — most often the men. Why is there little emphasis on how Reverend Samuel Parris lies to preserve his power, sacrificing Tituba in the process and setting off the motions in the play? Why is Thomas Putnam’s land-grabbing treated as a throwaway when it serves as a solid motive and evidence? Where is the blame on John Hathorne and Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth for their belief in spectral evidence and their refusal to admit to their misjudgments months later? Why are we encouraged to hate on Abigail Williams while we are encouraged to empathize with John Proctor — an adult man who has been unfaithful to his wife, who developed a sexual relationship with a child, and who beat his maid and threatened her constantly? Were all these men not supportive of the system only until it no longer benefited them?

Marasigan had an opportunity to wrestle with the misogyny that has made Miller’s text part of the canon of American drama, to challenge the inequities without necessarily erasing them. But even in his 2022 Virgin Lab Fest play Liberation, he doesn’t seem to take such chances, and instead he leans into the misogyny of the texts, maybe in the hopes of bringing the material closer to reality. But realism isn’t the only way to expose and express the truth, and in failing to imagine beyond the stage, Ang Pag-uusig becomes, borrowing a line from Chingbee Cruz’s “Authoring Autonomy,” political art that “participate[s] in the reproduction of the structural inequities they profess to condemn.”

The erasure of these nuances and connections in the staging — in terms of class, gender, and race — is symptomatic of the need to take dramaturgy more seriously in local theater, especially when concerning overtly political material. Ang Pag-uusig is material that can be appreciated within the four corners of the theater, but is enriched when it transcends the stage and is more deeply rooted in the context of our history. Our fractured political state and the language by which we communicate with allies and fight against our enemies are inherited from our colonizers. The reasons why Ang Pag-uusig falls short aren’t because things are lost in translation, but because its direction chooses to uphold the status quo. If Tanghalang Pilipino hopes to strengthen the work, not only as art but also as educational material, it must interrogate not only what stories it chooses to tell, but how it chooses to tell them, and must be willing to sacrifice something for it. – Rappler.com

‘Ang Pag-Uusig’ runs from February 17 to March 12, 2023 at the Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, CCP Blackbox Theater, Pasay City. For tickets, please visit Ticket2Me.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.