SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Trigger warning: This piece will discuss matters regarding sexual assault and harassment.

In the Philippines, sexual violence is as ingrained in our reality as it is in our fiction.

Whether its to make sense of our history of colonial subjugation or to unearth and process personal traumas, the depiction and discussion of rape is a fixation in the Philippine theater, a relationship made more complex by its association with instant acclaim. From theater stagings of classic films (i.e. Insiang and Himala) to one-woman shows mining the memory and trauma of survivors (i.e. Ang Dalagita’y Isang Bagay na Di Tunay na Buo) to historical retellings of the marginalized (i.e. Nana Rosa and Desaparesidos) to musicals that use it as a catalyst for its protagonists’ journeys (i.e. Huling El Bimbo), the stage has been a space for these secrets and actors lend themselves as a vessel for this suffering.

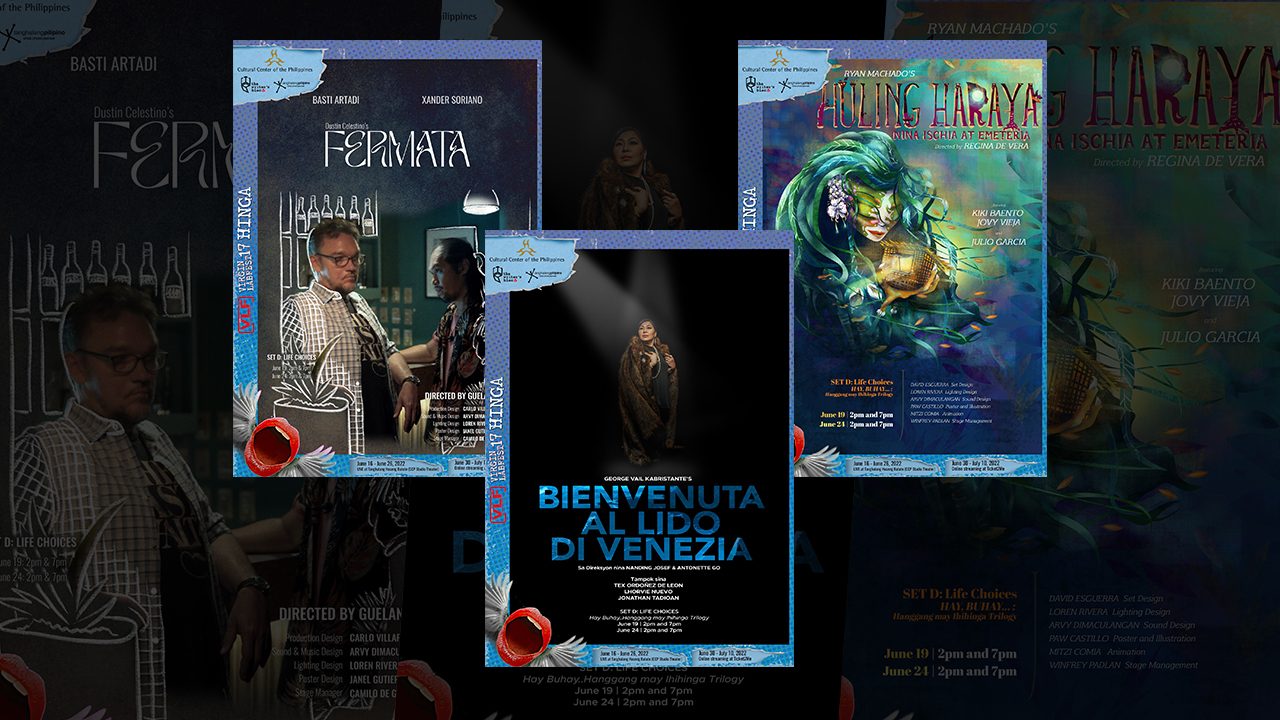

In this year’s Virgin Labfest alone, nearly half of selected material tackles some form of sexual harrassment and assault — from handling allegations in Bituing Marikit to its metaphorical representations in Walang Bago sa Dulang Ito to its vile depictions in Liberation. In Set D of Virgin Labfest, all three one-act plays depict the fractured lives not only of survivors but also witnesses and within this are layers of irony — as the legacy of Virgin Labfest and spaces like it are tainted by artists with similar allegations of misconduct and abuse.

In each, the audience is asked to explore all of the strange lines that must be drawn between emancipation and exploitation, the push-and-pull between forgiveness and justice, and the ways that confrontation and evasion can give way to healing.

Huling Haraya Nina Ischia at Emeteria (written by Ryan Machado, directed by Regina de Vera)

At a sari-sari store in Looc, Emeteria (Kiki Baento) prepares for the departure of her daughter Ischia (Jovy Vieja). While her mother packs her suitcase for college, Ischia hovers around, cracking jokes and attempting to convince her mother to drink Emperador with her. When she brings up the idea of moving in with her father’s new family, Emeteria clams up. Throughout the night, the two skirt around what they want to say, evading the real subject they must discuss on their final night together.

At first, such ambiguities seem like frustrating plot holes and poor direction. Is theater not a space for confrontation with our worst demons? Is it not possible to provide alternatives to what happens in reality? Is Emeteria’s escape into the fantastical realm not simply a cop-out? Huling Haraya seems like ‘night, Mother without the gun — the threat of disappearing materializing only through vague bird noises and easily missed rumbles.

Yet this initial reading is ungenerous and when one gives Huling Haraya the benefit of the doubt, its ambiguities seem less like plot holes and more like manifestations of its tenderness. How does one speak of trauma in the first place? What do you do when your mother drops your petition for justice? Who do you talk to about this guilt, this disappointment, if not each other? What do you do if how a person handles their trauma is different from yours? How do you extend empathy when such a complex ethical question is in your hands? While the audience seeks to have this trauma articulated, depicted, and resolved, something else forms instead — a cavity between mother and daughter, widened by silence.

In this distance between who they are and who they want to be for each other, Ischia and Emeteria are able to find clarity. Director Regina de Vera speaks of these evasive tactics as part of the “complexity of the feminine wound.” The absence of ready solutions, its refusal to explain away trauma and mend it with a singular conversation, is what separates Huling Haraya from every other play this year.

In her essay “How my OB became my therapist,” Anna Canlas connects her experience of myoma with her own feminine wounds, repeating the comforting words of her doctor: “Things come up to the surface when they’re ready to heal.” In Huling Haraya, healing cannot happen, at least not yet, and De Vera and writer Ryan Machado bravely choose to let such wounds be buried, recognizing that, no matter how much we want them to succeed, words fail too.

Bienvenuta Al Lido Di Venezia (written by George Vail Kabristante, directed by Nanding Josef and Antonette Go)

Bienvenuta Al Lido Di Venezia is at its most successful when it leans into the talents and the theatricality of Viola (Tex Ordoñez-De Leon) — a Filipino domestic helper taking care of a wealthy Contessa with Alzheimers. Inheritor of the Contessa’s will, both Viola and her live-in partner Maximo (Jonathan Tadioan) keep her barely alive to sustain their lives abroad. But when a mysterious journalist Charice (Lhorvie Nuevo) — or is it Sarah? — arrives and begins to probe into their lives, they move into ethically questionable territory to preserve their privileges.

From rape by the border patrol to punishments via castration, writer George Vail Kabristante and directors Nanding Josef and Antonette Go unveil the unspoken social conditions of our Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) in entrancing succession through Viola’s monologues. Bienvenuta Al Lido Di Venezia uses these stories to create a contrast between the provincial and the urban, between the idealized life of those overseas and the actuality of how our workers spend their days. The promise of generation wealth is emphasized by Carlo Villafuerte Pagunaling’s production design and Loren Rivera’s lighting design, physicalizing the lifestyle Viola and Maximo have grown accustomed to. Through the barrage of stories, the audience, like Charice (or is it Sarah?), is slowly conditioned to accept Viola and Maximo’s avarice — forcing listeners to empathize with the fear of losing what they’ve accrued, justifying the need to preserve what they have sacrificed for at whatever cost.

Yet just as the piece begins to peak, it dissolves like cotton candy in water. The one-act nature of the material does not allow for its antagonists to be fully fleshed out, nor does it give them ample time to build up to its homicidal conclusion. Bienvenuta Al Lido Di Venezia works better as a full-length play or even a film. But with its playwright gone, one cannot help but feel like this is where the buck ends. There is no encore, only quiet.

Fermata (written by Dustin Celestino, directed by Guelan Luarca)

During the first few minutes of Fermata, one wonders why it has garnered so much praise. The dialogue overlaps so uncomfortably and the actors aren’t listening to each other, we may as well have been watching a workshop. But the genius is in how, as the minutes tick by, it becomes apparent that this was all deliberate — part of a complicated tapestry of the male ego, the performance used to preserve it, that becomes recognizable only when it falls away.

Fermata follows Ben (Xander Soriano), the son of a recently deceased music icon, who visits a childhood friend Alex (Basti Artadi, brilliant in his relentlessness and vulnerability) at a jazz bar. When Ben reveals that he plans to write about how his father molested young male students, Alex attempts to reason with him — first with theories of alternate universes and ideas of false memories, then later with the truth. The play becomes an act of negotiating the past to inform the future and in its efforts to resolve this ethical standstill, Fermata becomes a discussion of how acts of trauma fracture perspectives.

Underneath the wrapper, Fermata is a jawbreaker. Director Guelan Luarca and writer Dustin Celestino create material that is impossible to swallow whole. Instead, it must be consumed slowly and painfully. It speaks about the small ways we violate consent, and the ways we turn victims into villains and villains into victims. It asks us who benefits from restorative justice and how such justice takes shape in the first place. Is there a future wherein both healing and equity can be achieved? What would such a future even look like?

Thanks to Luarca’s sensitive but still emotionally lacerating direction, the audience is never fully burdened with the weight of the confession, and are instead encouraged to pause and hold this space of rest. Especially in a world where noise is so common and calls to justice are result-oriented, at times even to the detriment of survivors, such silence can be a balm. But one cannot also ignore that it is this silence that allowed such violations to be buried, perpetuated. Does its ending ask one to focus on empathizing with the survivors or does it ultimately let the perpetrators and the systems that create them free?

In the weeks that I have sat with these feelings and ideas, I find myself returning to Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You. In creating it, Coel, like her protagonist Arabella, wrestles to find her peace amidst a violence that cannot be ignored. At some point in the seventh episode, she settles within this gray area and says:

“Are these facts a humbling reminder not to be so loud of my experiences or are they a reminder to shout? Can my shout help their silent screams? Is it time to serve a new tribe? I hope one day to know.”

One day, I hope so too. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.