SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Ilonggo Notes] The fascinating history behind Filipino frozen delights in Iloilo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/04/tl-frozen-delights.jpg)

A recent Facebook post of mine mentioned “bilbit,” and it elicited a flurry of responses about this now-rare frozen delight on a stick that was such a welcome treat during the summer months. Its purplish color and smooth texture recalled the soft fabric of velvet.

Bilbit may have started as a mispronunciation, Ilonggo-style. Bilbit, sometimes also called “ice drop” and considered a poor man’s delight, nevertheless was a close competitor to Twin Popsies and ice buko (milky with coconut strips, and a raisin at the tip), and cheaper. A bit lower down on the scale would be ice candy, a concoction of sugared water with fruity flavors, poured into a 1-2”-diameter plastic bag, and frozen. You just chew one end off and suck on it, until totally melted.

All these got me thinking about the past’s cold treats – the years of childhood, before specialty sorbets, sundaes, and ice cream parlors opened, recalling the ones that were peddled on the streets or made at home. The more expensive Magnolia in gallon tins were only for special days.

No ice cream without…ice

Ice in the 1800s was a valuable commodity and virtually unknown in the country outside of Manila. Dr. Benito Legarda is quoted in an Ambeth Ocampo column about a Royal Order in 1848 making ice importation tax-free. The British firm Russel & Sturgis (which later had a branch in Iloilo) was the first to import; it opened an ice plant in Manila but then went bankrupt in the 1880s. Ilongga food historian Doreen Fernandez notes that ice cream was served in 1898 in a grand banquet held to ratify the Philippine Declaration of Independence.

A year later, Willliam Schober arrived as a cook in the US Army. After the dust settled, he started an ice cream business, introducing “magnolia ice cream;” the company was eventually purchased by San Miguel Brewery in 1925 and the name was retained.

Iloilo, being the second most important city in the country, would not be left behind in trying this novel treat, though it may not have been that popular. Emily Bronson Conger, writes in An Ohio Woman in the Philippines (1904) than on the 4th of July 1900, at a reception in Jaro for Filipino families who had accommodated the American soldiers, “…we were served commissary refreshments such as ice cream and cake, but the guests there thought of it as a very poor banquet, for such pretentious people as the officers. The Filipinos usually have a 10- or 12-course meal at festivals or banquets…”

The rarity of the treat meant that it had to be a very special occasion, when ice could be shipped to Iloilo. In 1905 at a reception for US Secretary of War (and future US President) Taft and Alice Roosevelt, daughter of then US President Teddy Roosevelt, Mrs. Campbell Dauncey writes in An Englishwoman in the Philippines (1905), in typical sarcastic tone, “(we) consoled our hearts very successfully with cold mutton — a treat from the Cold Storage in Manila — which would have made up to us for anything. You see, you can’t have cold meat in this climate without ice to cool it on, and we have been without ice for so many wretched months….”

‘Dirty’ ice cream

With improved shipping, transport, and technology, ice gradually became more available and ice plants were set up in Iloilo. The Panay ice plant near Muelle Loney has art deco architectural features, popular in the 1930s. Cold storage and ice cream manufacturing became more common during the Commonwealth years. There would be ambulant vendors and peddlers of foodstuff, and this would naturally include the ice creams.

How did it become known as “dirty” ice cream?

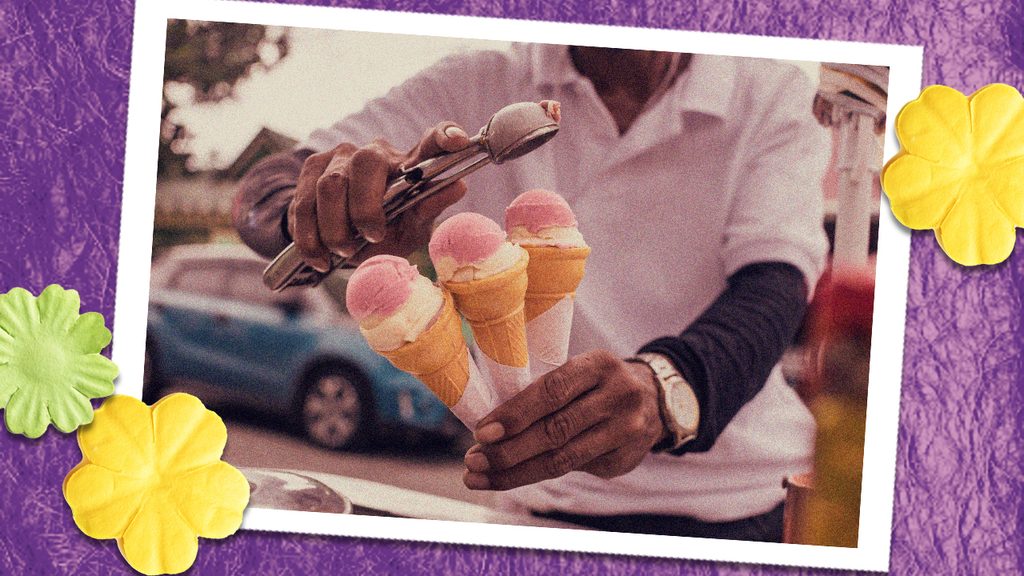

The origins of the term “dirty ice cream” are not entirely clear. Whoever invented the term may have tried to make a distinction between what was “clean” and nicely wrapped and the “other” competition. During the ’60s, sorbeteros would peddle different varieties of ice cream from the yellow and blue Magnolia carts. Other Ilonggo sorbete brands, such as Corona, had their own carts. It may have been so called because of the way the sorbetero would take our coins or bills and give us change – between grabbing a cone, the flat spatula, and piling on the colorful flavors – without so much as wiping his hands. Remember, we were told that money was “dirty” because many people would handle it.

Still, those labels did not stop us from enjoying the cheaper guilty pleasures, whether on a crispy barquillos–type cone, or scraped onto a pan de leche, open sandwich-style. Magnolia ice cream would be sold by the scoop and the cones would be the blander, softer brown wafers. However, the dirty ice cream vendor would be more likely to give you an extra dollop, or “paaman,” and the lines would be longer, especially outside the school gates.

In the ’80s ice cream parlors became popular. Sundaes, parfaits, banana splits, cobblers, and different varieties of ice cream with new flavors, toppings, and combinations were introduced after the classic ube, macapuno, mantecado, vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. We would look forward to the “Flavor of the Month,” which would come out in a limited edition, and if popular, would be repeated the following year, or even made a staple.

Other popular brands like Arce Dairy would not be easily available in Iloilo back in those days. Soft-serve ice cream coming out of dispensing machines at Eugene’s, and later at Hans Bake Shop, were the most popular in the Calle Real area. Gelatos would appear years later.

While I was working in Vietnam in the late ’80s, a very popular ice cream parlor, Kem Bach Dang, had one basic flavor: coconut, bedecked with different types of stewed and sweetened fruits, and nicely served inside a coconut. Vietnamese ice cream was noticeably less sweet than Philippine counterparts.

Japanese origins of halo-halo

Food historians note that it was the Japanese who first came up with a version of the now thoroughly filipinized halo-halo. Osawa, in A Japanese in the Philippines (1981), writes: “…Another line of business monopolized by the Japanese [in the Philippines] was called mongo-ya. Mongo is a Tagalog word meaning red beans. What was sold for ten centavos was a plateful of cooked red beans heaped with ground ice, topped with sugar and milk. The business could be started with a small capital outlay, and some Japanese, after a few years as farming immigrants, turned proprietors of mongo-ya.”

However, this all disappeared during the war years. I remember having homemade mongo con yelo during summertime, and other single-ingredient coolers like leche con yelo and mais con yelo. A favorite during the Holy Week was sansaw, a cool iced drink made from arnibal (brown sugar syrup) with bits of local gelatin, or agar-agar – the one that comes in bars and feels like a loofah – and sago. It is the Ilonggo version of sago at gulaman.

A Japanese dessert, kakigori, has sweetened beans with ice. It used to be prepared from snow during the winter months, until ice made it possible all year. Probably inspired by this, halo-halo has evolved into a genuinely iconic Philippine dessert, with ingredients including sweetened bits of mongo, saba banana, kamote, kaong, nata de coco, red beans, leche flan, ube halaya, corn kernels, buko strips, pinipig, evaporated milk, and ice cream. A street side halo-halo joint in Silay City, known as Calle Luna, prides itself on 15 humongous versions of halo-halo.

Variations of the shaved ice dessert may be found all over Southeast Asia, from Malaysia and Indonesia (ais kacang, chendol), Vietnam and Cambodia (che) and Laos and Thailand (nam kang sai). Here toppings may include jackfruit, grass jelly, pandan-flavored tapioca flour noodles, sticky rice balls with water chestnuts, coconut cream, palm sugar syrup, jasmine scents, and soaked basil seeds.

Returning now to bilbit and dirty ice cream, these two seem to be making a comeback, with local entrepreneurs leading the way. Sanitation standards and food handling practices have improved over the decades, so it is “dirty” no longer, but the appellation remains as a quaint reminder of local food and cultural history. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Ilonggo Notes] The games we used to play](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/03/games_compressed-scaled.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.