SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“Everything that you see here was once a sugarcane plantation,” says Monico Bebita, pointing out the expansive rice fields as we trace our steps amidst grass-covered pathwalks. I decided to explore the remaining simboryos of the town of Panay, famous for its Spanish-era church and the iconic church bell, dubbed the largest in all of Asia.

Randell of Panay’s Tourism Office told me that there were about 6–7 primitive simboryos spread in the different barangays of Panay. I asked if I could visit these simboryos. He then referred me to Monico, whom I met a long time ago during a cultural mapping workshop and who now works for the local government.

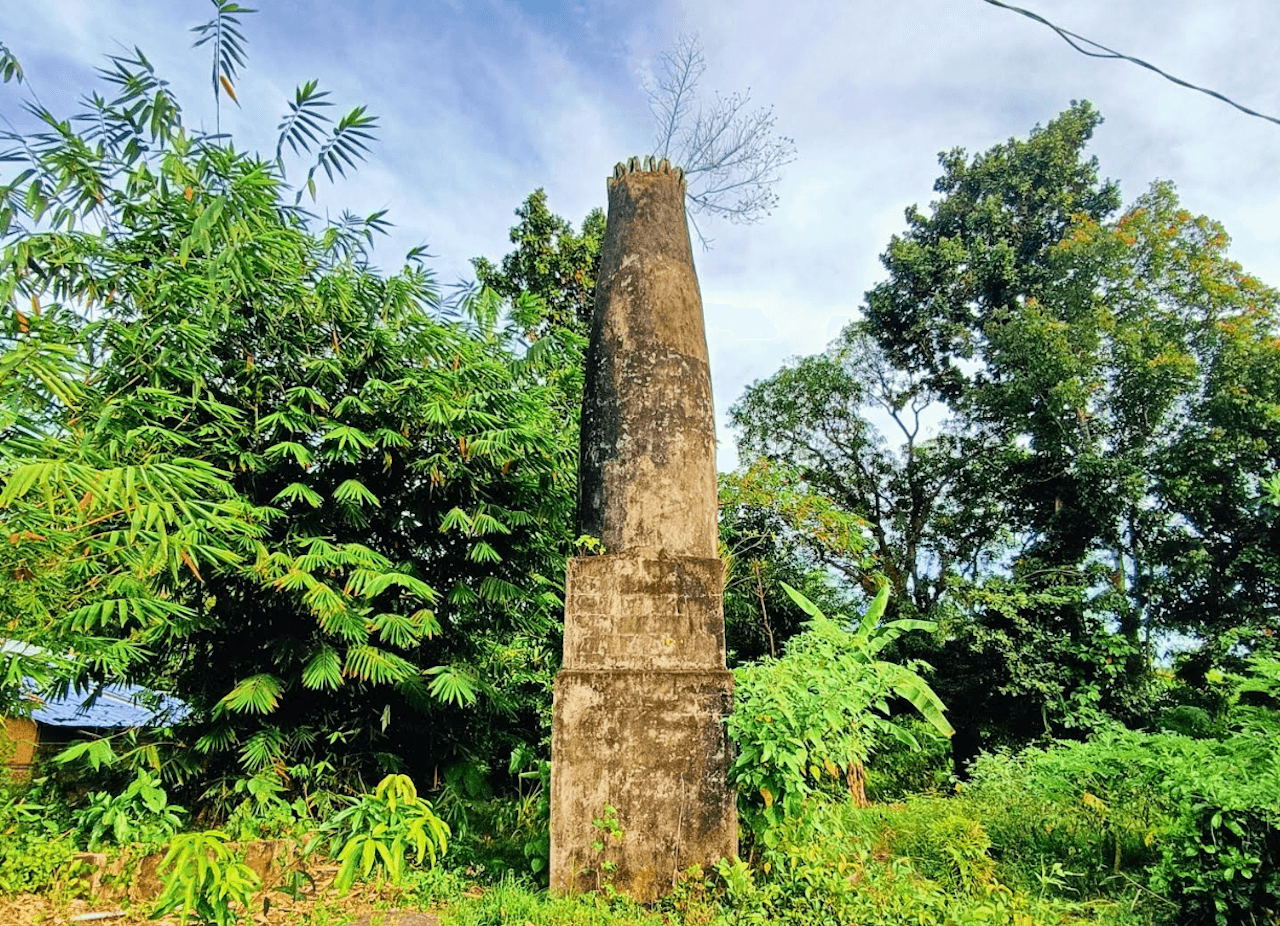

Simboryos, or smokestacks, are now symbols of a bygone era. They remind me of a time when sugar cane was gold. Simboryos were part of sugar mills that once dotted the landscape of this part of Capiz, functioning as chimneys or funnels where smoke emitted from burning wood or dried sugarcane bark while cooking molasses or muscovado was discharged.

It was a sweltering afternoon. It was already four o’clock, but March’s prolonged daytime meant challenging fieldwork. El Niño has already begun to cast its spell and Monico was complaining that in a matter of weeks, the rice fields, still green at the time, would turn gold and finally brown, until the earth would crack because of the drought. Taking a tricycle ride, Monico and I treaded the dirt road that traversed once we turned left from the highway and straight to a two-lane path that halved the rice fields. I imagine that a long time ago, no house stood along the road — just hectares upon hectares of sugarcane plantations.

Our first stop was the ruined simboryo of Bago Chiquito. It stands just inches away from a river and I fear that when the soil keeps eroding, the simboryo will eventually fall off. Monico told me that the river itself is now dead because water stopped flowing from the main source, Paslang, in the nearby town of Panitan. He recalled that the river used to be deep and provided water to the rice fields.

I took pictures and noticed that the simboryos were made of bricks and cement. Monico told me that the bricks came all the way from Capiz (in Roxas City) and some other parts, like Iloilo. One could easily identify them because the names of the manufacturer and the place where they were made were engraved on each brick. The brick-making industry in Capiz has also been around for a long time.

We visited three more sites, all of which presented the same scenario. While the smoke stacks are still standing, they have become useless over time. The other parts of the sugar mill, like the caua, where the sugar extract was cooked until turned into molasses, the gears, and the cauldrons, were either damaged or lost.

Until the 1980s, the land that stretches from just outside Panay’s Poblacion until Candual, Anhawon, Bago Chiquito, and Agbanban were all sugarcane plantations, hence the presence of simboryos, which meant that there were sugar mills in these places. Before the war, sugar figured in as among the top agricultural products of Capiz, next only to rice, which was then the rice granary of Western Visayas. The simboryos were strategically located near the rivulets and tributaries of the Panay River, where, I am told, sugarcane was loaded on a conduccion, a type of wooden vessel, and transported to Pilar or traded somewhere else. Unlike in the town of Dumalag, where the Panay Railway passes through the sugar central, there was no railway or highway in this area; hence, the waterways served their practical purpose.

In an unpublished report written in 1963 by Jesus Bermejo of Panay, he explained the tedious process of extracting juice from sugar cane and processing it to become molasses — all these were done in the sugar mills.

“The sugar canes are cut and placed in carts, which are drawn by the carabaos to the sugar mills. The sugarcanes are placed between rollers and pressed. The juice comes out and it is put through a strainer to take away the pulp. For the first boiling, a pipe directs the juice into the first cauldron.

“The boiled juice is transferred into an elevated tank that is capable of containing 75 petroleum cans of juice. The juice stays in this tank for about an hour to let the sediment settle at the bottom.

“The juice is distributed into three cauldrons and is again boiled. While the juice is boiling, the dirt floats on the surface. The dirt is taken away by means of big ladles made of half of the petroleum can.

“After one and a half hours of boiling, the chief cook, called maestro, tests the thickness of the syrup. When it is ready, the thick syrup is transferred into a wooden container measuring 10 feet by 6 feet. The syrup is allowed to cool and dry. When it is almost dry, two laborers with spades mix the sugar in the same way as mixing cement. Then they would use wooden rollers to press the big lumps of sugar. They do this until the sugar becomes fine in texture. The product is called muscovado or brown sugar. Muscovado is measured by cavans and put into bayons, ready for market.

“Another method of preparing sugar for market is called pinarak. The syrup is poured into parak, which are small round molds. These molds are as big as plates and saucers and are about two inches or one inch thick. As the syrup cools in the molds, it also hardens. After one-half hour, the sugar is hard enough. The men turn the molds upside down and the sugar comes off. The molded blocks of sugar are put one over the other and wrapped in dried sugarcane leaves. Then they are ready for the market.

At the peak of the sugar industry, farmers earned more in sugarcane farming and small-scale sugar manufacturing than in raising rice or corn. A farmer earned 60–80 cavans per hectare and would sell each cavan for P20. In fact, the sugar industry was then deemed a route towards improving the lives of farmers in Panay. Alas, with the decline of the sugar industry in the 1970s and 1980s, this industry in Panay also suffered. Eventually, landowners converted their sugarcane estates into rice fields. The sugar mills were left to rot, and the metal cauldrons were eventually sold.

One local told me to visit Maayon, a town nearby, where a collector once bought most of the cauldrons in the area. Today, the ruins of simboryo – now in dismal condition, are what remain to remind us of what a bustling place these sugarcane plantations were once upon a time. – Rappler.com

Christian George Acevedo is a librarian, writer, and heritage advocate from Roxas City, Capiz.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.