SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Last weekend, I went to Calbayog City, Samar with a colleague to turn over teacher’s kits to 250 public school teachers assigned in remote schools from either the islands or the uplands.

We were ready to serve as a bridge between our generous donors and our chosen recipients, and ready to have a personal encounter with our teachers who are largely overworked, underpaid, and unappreciated. We were ready to celebrate World Teachers’ Day with them.

What we were not ready for were the stories that they generously shared with us – stories that tugged at our heartstrings and made us realize anew why our teachers should, indeed, be put on a pedestal as our country’s modern-day heroes. (READ: ‘More than just a job’: Teachers, students voice out important role of educators)

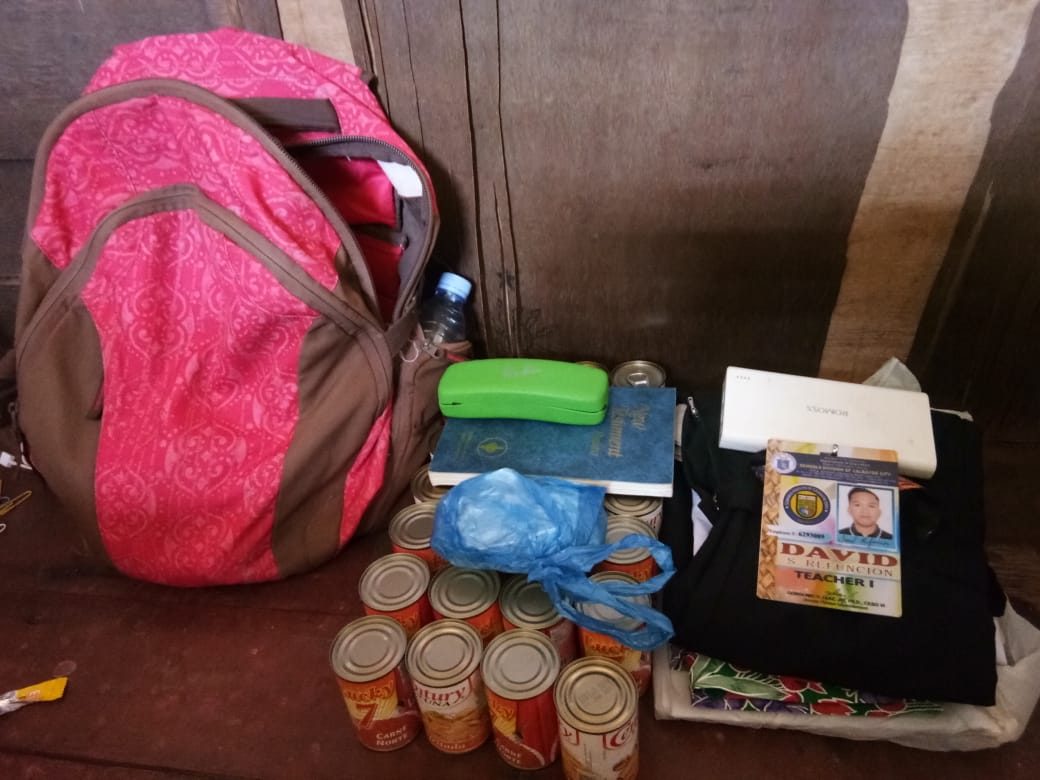

David Refuncion teaches in Mabini I Elementary School, a school situated in one of Calbayog’s farthest mountains. Refuncion, along with 7 other teachers from their clustered school, travel for 11 hours just to get to his students – 2 to 3 hours aboard a multicab, then a habal-habal and, finally, a boat, before he would have to walk across rivers, rice fields, and hills for another 6 to 8 hours.

Their travel becomes longer, riskier, and more challenging when they do it under the pouring rain because the water in the river rises and its current becomes strong. The mountains and rice fields they navigate become murky and slippery. Armed conflict between members of the New People’s Army and private armed groups also poses a serious challenge to them and the entire community.

Adrian Benecario, from Calilihan Elementary School, has to regularly contend with landslides during his 5 to 6 hours of travel on foot to the hinterland.

Both young teachers are witness to how their students are living in abject poverty.

They have students who walk miles barefoot and are used to attending classes on empty stomachs. There are those who can’t afford to buy something as basic as paper and pencil, and just have to rely on the generosity of their classmates. There are those who use plastic grocery bags for their school bags. There are those who have to skip classes because their parents need an extra hand in the farm.

When someone in the village gets sick, the parents automatically turn to the teachers for medicines because the nearest health center is miles away. (READ: [OPINION] A teacher’s voice)

There’s also no electricity in their place so the teachers have to use a flashlight or kerosene lamp when they are working on their Daily Lesson Log (DLL). (READ: FAST FACTS: What you need to know about the PH education system)

They also shared what, for me, was the worst and most heart-rending story. They said that some of their female students, the youngest of whom are in Grade 3, have to quit school altogether because their parents are forced to marry them off.

They do it for two reasons: to rid themselves of the burden of feeding another mouth, and for the “payment” that they will receive from the man who will be their daughter’s husband.

For P30,000 (which is usually given to them in installments) and a small pig or goat, these little girls are given away to any man who has the capacity to pay.

As a mother myself, that is the story that really broke my heart.

Meanwhile, Mary Jane Ebardone and Mariah Kim Oite are co-teachers in Cag-anahaw Elementary School.

They have to be extremely careful when going to school as paths can be steep and slippery, and one misstep can cause them to stumble down cliffs. Previously, they would reach their school by bamboo rafting for four hours, climbing four mountains, and crossing a treacherous river that snakes around those mountains. But since the river has gotten shallow due to landslides, they now have to walk all the way to the barrio where they teach.

Communication remains a challenge due to the weak and unpredictable cell signal in the village. (READ: Leyte teachers appeal for better internet connectivity)

On December 28, 2018, the barrio was wiped out by Typhoon Usman.

Their school that sits atop a plateau was one of the few structures that survived the catastrophe. The floodwater, though, still reached the roof of the covered court.

It was only through the bayanihan of the neighboring communities that Barangay Cag-anahaw was able to slowly rise again.

Although it was hard for the two young teachers to accept that their students could not go to school because they had to be with their families in picking up the pieces of their shattered lives, they fully understood the situation.

After all, given the choice between education and survival, any one of us will certainly choose the latter.

Another two teachers that we talked to were Ricky Balat and Rhio Amor who both teach in Guin-ansan Almagro Island.

Between the months of August and February, when the most intense monsoon winds blow, the islands get more isolated from the rest of the city because no boat dares to head to the open sea. During this season, there is scarcely any food. People have to make do with wild grass and any available root crops.

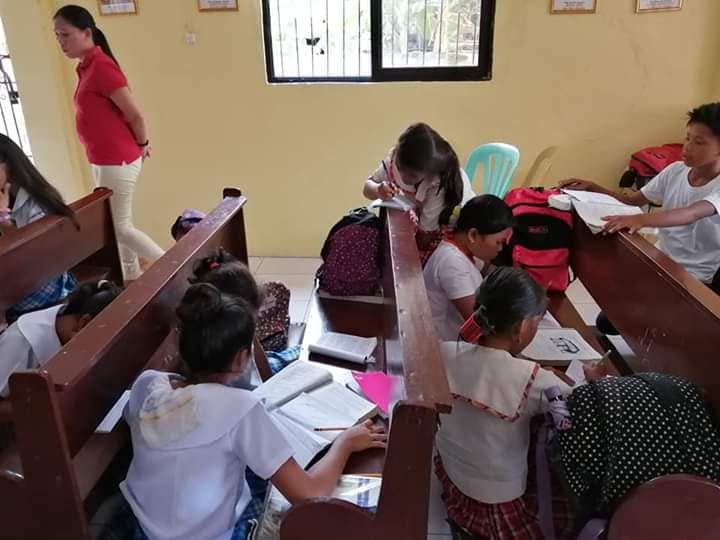

Although there are schools in the central part of Guin-ansan Almagro, those in far-flung areas have to make do with holding classes inside churches or improvised classrooms. The students’ houses are a long walk from these improvised “schools” and the unpaved roads that they tread are typically rough and muddy. Sometimes, there are even snakes slithering about.

Balat, in particular, teaches classes in San Vicente Ferrer Parish.

The monthly salary of our entry-level teachers is only P20,000. Some of them do not receive hardship allowances despite the risks that they face on a daily basis just to do their job.

They are even required to make a cash contribution for unit meets, competitions, and other events. They also buy their supplies from their own pockets.

After all the deductions for taxes, government-related contributions and all sorts of personal loans, the teachers are left with a meager take-home pay. Yet, they still try to help their students in any way they can.

Asked what they would request for should there be generous souls ready to grant their wish, none of them expressed a desire for themselves. They listed down school supplies, slippers, playground, classrooms, and books. All for the students.

They just do what they do because they love teaching, their students, and the community.

For these teachers, it is enough that their students greet them with happy faces whenever they arrive at the village. The fruits and vegetables generously given to them in exchange for the medicines and other supplies that they provide for the families are loaded with sincere gratitude.

They also realize that, in their own ways, they are making a difference in the lives of children and their families. This is what keeps them going, day after day.

If that is not heroism, I don’t know what is. – Rappler.com

For all those who are willing to help with Team Pilipinas’ outreach initiatives, you may email teamph.volunteers@gmail.com or call (0915) 3801977.

Lorelei Baldonado Aquino, 46, is a University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman alumna. She works as a freelance writer and an active volunteer for Team Pilipinas, a group established for those who want to do their own small share to be part of the solution to our country’s myriad of problems. She is also the blogger behind Mom on a Mission.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.