SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

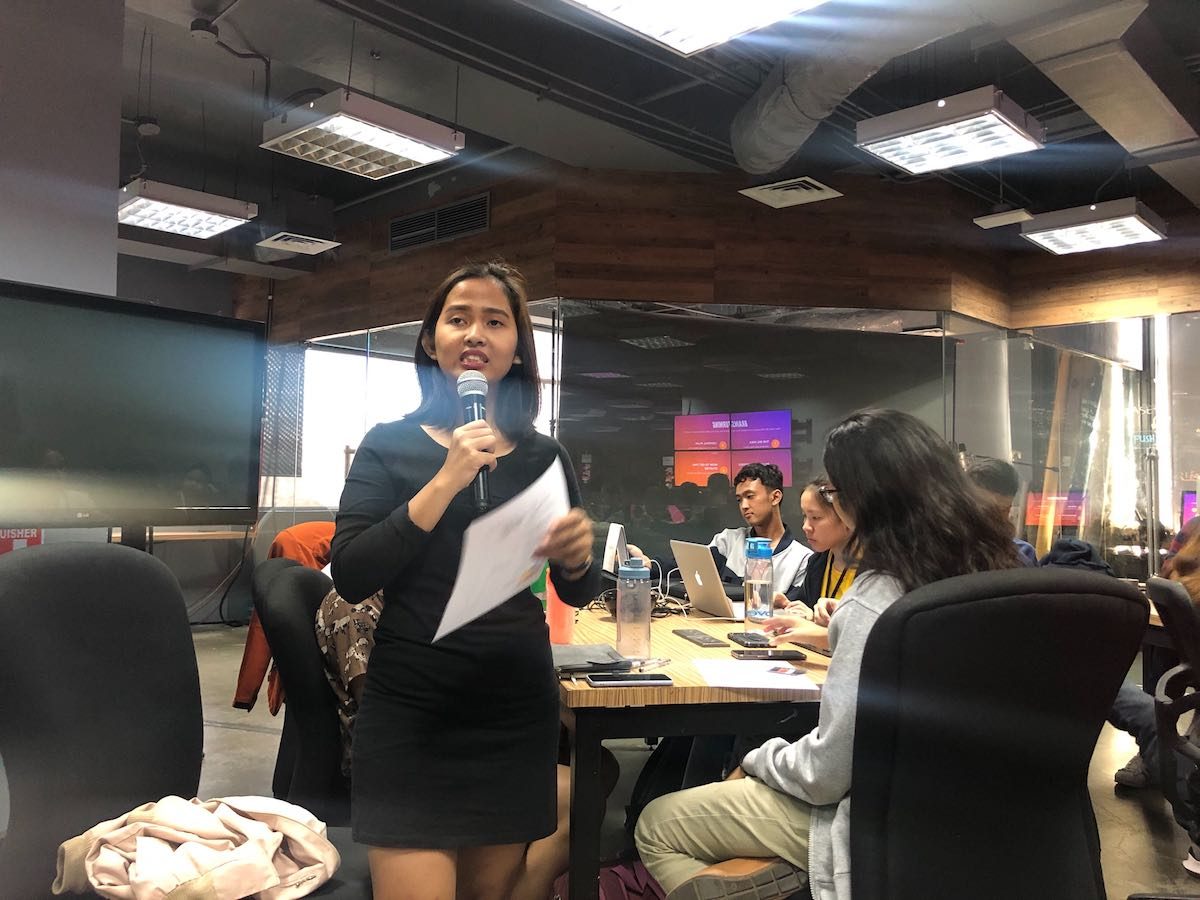

MANILA, Philippines – Students from over 30 campus publications within Metro Manila and nearby provinces gathered on Saturday, February 22, to discuss the problems young journalists face at a time when press freedom is under attack.

The huddle, hosted by Rappler’s civic engagement arm MovePH, tackled the current state of campus journalism.

In today’s political climate where trolls and disinformation campaigns proliferate and the quest for truth becomes an everyday feat, student journalists are now facing a new set of problems in the same way journalists from mainstream and alternative publications are.

The intimidation of the press now covers even campus publications as well.

Students in the huddle identified the biggest problems their publications have faced in terms of pre-publication, publication, and post-publication. Across all 3 categories, the grave problems that resonated with many of the campus publications were varying degrees of administration intervention, which ultimately results in lack of autonomy for campus publications.

Editorial independence

While student publications should ideally be independently published by students, certain administrations still tend to intervene, and in different ways.

Beatrice Puente, editor-in-chief of the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Philippine Collegian, recalled when two of her co-members were barred from taking their publication’s editorial examinations and were therefore disqualified from running for editor-in-chief. (READ: Is Philippine Collegian facing a press freedom issue?)

Puente recounted that the selection process of their editorial board was initiated by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, whereas editors from other publications have the authority to directly appoint their successors instead.

“Na-realize namin, kung doon pa lang sa simulang process ng pagbuo ng editorial board, sa pagbuo ng susunod na leader ng publication, paano pang magkakaroon ng isang democratic na proseso doon sa university, in essence?” Puente said.

(We realized that, if in the first place, this was how the process of selecting the editorial board and the next leaders of the publication worked, how can we achieve a democratic process in the university, in essence?)

Another characteristic of student publications is that the school administration still provides them with resources and funding.

Many students shared that lack of resources proved to be a major hurdle in producing their stories, and that publishing critical stories may pose threats to campus publications – some more than others, depending on how rigid the universities’ administrations are.

“One of our groupmates got to share about the free tuition [law], which makes them more prone to censorship. If they have stories that are more critical of the government, they might slash their funding, which might be detrimental to the operations of the publication,” Russell Ku of Ateneo de Manila University’s The GUIDON shared, on behalf of his group composed of different publications.

The College Editors Guild of the Philippines said some 200 student publications from state and local universities and colleges nationwide are on the brink of being defunded partly due to the free tuition law.

The law’s implementing rules and regulations do not require the collection of student publication fees. (READ: The different faces of press freedom violations vs campus journalists)

Many students also talked about how their respective school administrations tend to react negatively toward articles that don’t align with their personal beliefs, or with the school’s values.

“It’s really frowned upon to publish articles that are about the state of the nation and just in general – politics, government, LGBTQ+. I understand we’re from a Catholic school; however, I don’t think it’s good to box students in the privilege they’re put into,” said a participant from a school in Pasig City.

Other school administrations would go as far as outright censorship.

Students from The Bosun of the University of Asia and the Pacific recalled that one of their columnists wrote about the inconsistencies of their school’s Center of Student Affairs. After the column was published, the columnist and members of the editorial board were initially called by administrators to take down the story. It was later negotiated that they could just modify the column.

Meanwhile, members of De La Salle University Manila’s Ang Pahayagang Plaridel shared how one of their special issues was deemed too “vulgar” by the administration. Circulation was later halted.

What’s next?

Students called on the government to revisit the proposed Campus Press Freedom Act, which stipulates provisions not included in the Campus Journalism Act of 1991. (READ: Does the Campus Journalism Act protect press freedom?)

The proposed Campus Press Freedom Act explicitly includes penalties for school administrations or persons who interfere with the operations of any student publication, allowing for greater independence on the part of campus journalists.

“It will require their admins to recognize their right to freely operate and publish,” said Twitter user @heyr0n.

It will strengthen the independence of campus publications inside their respective institutions and require their admins to recognize their right to freely operate and publish, provide their necessary funds, and make any form of admin intervention illegal.#CourageOn

(2/2)

Students also suggested creating awareness campaigns for people to know why addressing the gaps in the existing Campus Journalism Act is especially urgent in today’s political climate.

“The awareness of the campus press freedom bill is lacking, so we want to spread the different nuances of the current [Campus Journalism Act] and why we need to pass the bill,” said Ku.

Other students also proposed a unified statement from publications against censorship, and possibly a petition that may be forwarded to school administrations.

“The solidarity of campus journalists across different schools and universities can be a powerful catalyst for strengthening campus press freedom,” Clare Pillos of The Bosun tweeted.

The solidarity of campus journalists across different schools and universities can be a powerful catalyst for strengthening campus press freedom. #CourageOn

Ultimately, students pointed out how hurdles faced by campus journalists threaten the quest for truth.

“The admin doesn’t lose anything from the absence of student publications, but society loses an arm and a chance in shifting towards a better world,” one participant tweeted.

Hoping to strengthen the links between campus publications, student organizations, and advocates all over the Philippines, Rappler’s civic engagement arm also launched the revamped MovePH network during the huddle.

The MovePH network aims to provide opportunities for greater citizen participation that shapes the news agenda and catalyzes concrete actions for positive social change. – Rappler.com

Do you want to know more about the MovePH network and be part of an ecosystem of civic action enablers and doers collaborating towards sustainable progress and nation-building? Send an email to move.ph@rappler.com!

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.