SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Like in similarly situated countries, press freedom has been consistently hammered in Egypt. Yet, despite the threats being thrown at her news outlet, Lina Attalah, editor-in-chief of Egyptian independent media outlet Mada Masr, chooses to fight back.

Attalah, who was chosen as one of Time’s “100 Most Influential People of 2020,” has displayed an extraordinary track record of brave and hard-hitting reportage. In 2013, she co-founded Mada Masr. Seven years later, Attalah continues to lead Mada Masr as its editor in chief.

In an essay about Attalah for TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of 2020, Rappler’s Maria Ressa, who was recognized as Time’s “Person of the Year” in 2018, highlighted Mada Masr’s pursuit to “do stories they know will bring ‘good trouble.’” Mada Masr has treaded this path even in the midst of self-censorship by other Egyptian news outlets following a state-led campaign accusing critical media of spreading lies and threatening legal action over reports that authorities consider as “fake news.”

Mada Masr’s decision to stay independent and continue reporting has been met with several onslaughts by state forces, many of which targeted its chief editor.

Playing with fire

One of Attalah’s first brush with media repression was during a 2011 demonstration in Cairo. Attalah, who was the managing editor of Al-Masry al-Youm’s English edition at the time, reported that cops pulled her hair and kicked her in the face and in the back.

In 2019, security forces raided the Mada Masr office and detained several of the news group’s journalists, including Attalah. This came after the site released an investigative piece on the reassignment of the Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi‘s son to a long-term position at Egypt’s diplomatic delegation in Moscow.

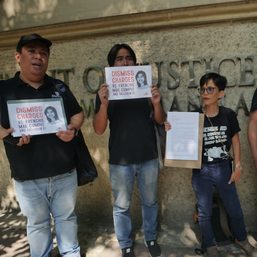

Attalah’s most recent brush with media silencing was her arrest in May 2020. Authorities confiscated Attalah’s phone and apprehended her for undisclosed charges while she was in the middle of interviewing the mother of an imprisoned activist. Attalah was reportedly denied to meet with Mada Masr’s lawyer following the arrest and later paid 2,000 Egyptian pounds to be released on bail.

Mada Masr is also one of many news websites blocked by the Egyptian government for “spreading lies.” The website is accessible in Egypt through the use of virtual private networks. Mada Masr continues to report on Egypt in Arabic and English, despite the attacks.

The challenges faced by Attalah and the rest of Mada Masr are part of the growing clampdown on media under the leadership of Sisi. Egypt was named the third-worst jailer of journalists in the world by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in 2019, with the report highlighting cases of false charges and violent arrests.

Hitting home

Attalah’s adherence to critical journalism, and the consequences of pursuing it in the face of censorship, draws striking parallels with Philippine media.

ABS-CBN, one of the top media networks in the country, went off-air on May 5 after a cease-and-desist order from the National Telecommunications Commission, drastically affecting the local media industry.

The media giant’s closure came after the House of Representatives dragged its feet in tackling ABS-CBN’s franchise renewal bills, and after President Rodrigo Duterte repeatedly threatened to close ABS-CBN. Lawmakers eventually rejected the network’s franchise application.

In June, Ressa and former Rappler employee Reynaldo Santos Jr. were convicted of cyber libel over charges filed by businessman Wilfredo Keng in a case that tested the 8-year-old Philippine cybercrime law.

The attacks were not limited to the weaponization of the law. CPJ reported at least 84 journalists were killed in the Philippines between 1992 to 2020. The Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility and the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines found 61 reported incidents of threats against the press from January 2019 to April 2020.

In these brazen attempts to muzzle media, journalists like Attalah set the standard for fighting back.

In a June interview with The Africa Report, Attalah was asked if there were issues that should not be covered by media outlets to ensure their survival.

Attalah responded: “We don’t ask ourselves that question. We do not believe that certain important issues should not be addressed to ensure our survival. In that case, our very survival would be meaningless.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.