SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

At a glance

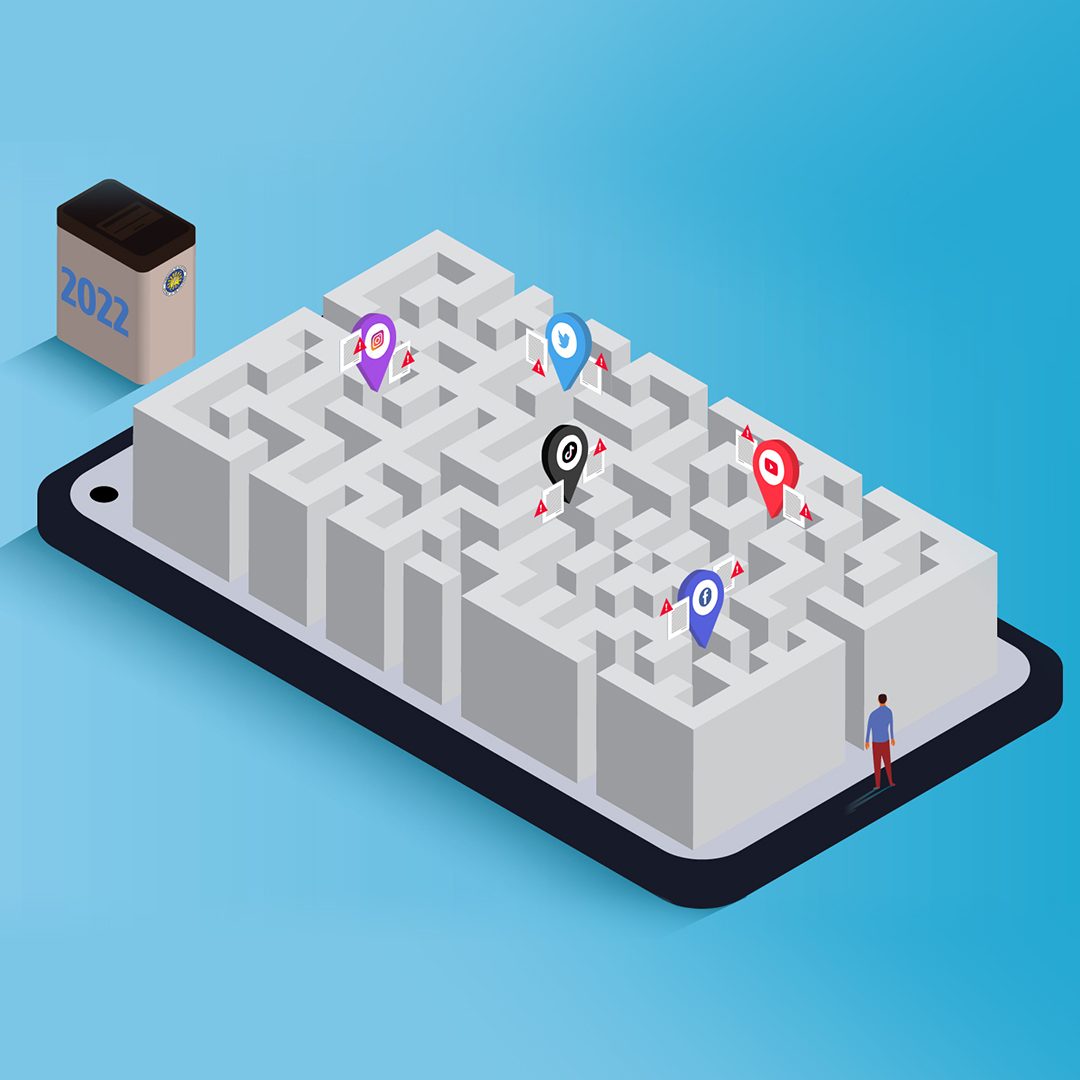

- Less than a year before the 2022 presidential elections in the Philippines, problems with social media platforms have only gotten worse. They included fake accounts, hate speech, and disinformation.

- The gaps in the platforms’ policies continue to threaten the electoral process, as harmful content and falsehoods are expected to increase during election season.

- Tech platforms vowed to help secure the integrity of the Philippine elections, but to date their actual plans are not known and have yet to be scrutinized. This is crucial as the country witnessed firsthand the weaponization of social media starting in 2016.

- Facebook and Twitter said they would provide more information as election day nears, despite politicians starting campaigns as early as now, a year before the E-Day.

A year before the 2022 presidential election in the Philippines, the most popular social media platforms continue to pose threats to the integrity of the polls.

Policies by Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and YouTube don’t provide answers to how they will address the issues of disinformation, political advertisements, data breach, and hate speech in an increasingly toxic environment. (READ: Propaganda war: Weaponizing the internet)

Social media was a key factor in Rodrigo Duterte’s victory in 2016, and his troll armies and fake news machinations have only worsened until now. A former Facebook executive called the country “Patient Zero” in the global war on disinformation, while a whistleblower said the Philippines was Cambridge Analytica’s “petri dish.”

The threat to credible election information is even bigger, as more people have gotten online due to pandemic-imposed lockdowns. Since the crisis began in March 2020, there have been 4.2 million more internet users in the country dubbed as the world’s social media capital.

In the United States early this year, hundreds of supporters of then-president Donald Trump stormed the US Capitol over false claims of election fraud disseminated on social media.

Similar forms of real world harm spurred by online attacks and disinformation could also happen in relation to Philippine elections if social media platforms don’t implement structural changes.

Rappler looks into the gaps in the policies of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube and how these pose problems in the upcoming elections. (READ: Social media lessons from the 2020 US presidential elections)

Gaps in disinformation policies

Facebook, with around 83 million users from the Philippines, has been the go-to place for campaign teams and influence operators.

Facebook has long struggled to fight disinformation on its platform, even as it partnered with independent, third-party fact-checking organizations, including Rappler and Vera Files in the Philippines.

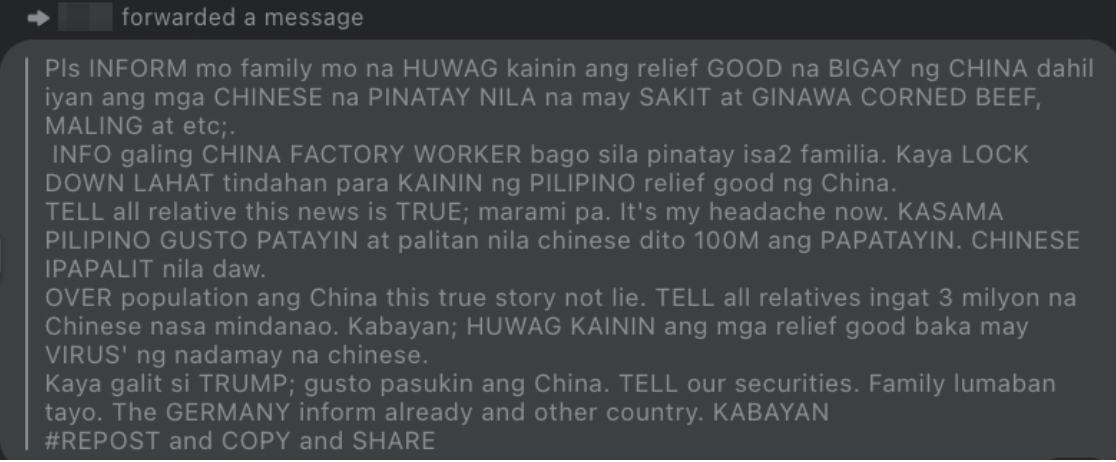

Facebook has shut down multiple fake accounts, including the network of Duterte’s social media campaign manager Nic Gabunada. But the company has failed to follow through, as many accounts were able to evade scrutiny and to create new ones to spread disinformation. (READ: Cat-and-mouse game: Twinmark fake network still thrives on Facebook)

While helpful, fact-checking is still not enough. Studies have found that lies travel faster than the truth. By the time a falsehood is debunked, it has already reached thousands of people.

“We now do more than ever to stop election interference…. We’re working closely with civil society, electoral authorities, and the industry, and will make further announcements on our election efforts in the lead up to next year’s vote,” a Facebook spokesperson told Rappler.

Facebook’s fact-checking program also focuses on publicly available posts, which means it does not cover information spread via Facebook Messenger, the top messaging platform in the country.

Facebook also exempts politicians’ and candidates’ posts from being fact-checked. What if these personalities spread falsehoods via their accounts?

The platform maintains that the people, not tech companies, should censor politicians.

Facebook’s stance is in stark contrast to Twitter’s action when it placed a fact-check warning on Trump’s tweets in 2020. Twitter is currently reviewing its approach to world leaders, and has yet to confirm if it will apply the same action to Filipino politicians.

Twitter, though, does not have third-party fact-checking partnerships. In other countries, it puts labels and warning messages on government and state-affiliated media accounts. There’s no word either if this feature will be available in the Philippines.

Twitter, however, has a prompt that asks users to read the story first before retweeting. It is a feature that Facebook is just starting to roll out in select countries.

According to Monrawee Ampolpittayanant, head of Twitter’s public policy and philanthropy for Southeast Asia, their teams are “working round the clock” to protect the integrity of civic events, including the 2022 Philippine elections.

“We look forward to working with all relevant stakeholders and entities from government and civil society as details about the election are confirmed in due course. We will draw on insights and lessons from previous elections and continue to iterate our approach to protecting the health of the public conversation,” Ampolpittayanant said in response to Rappler.

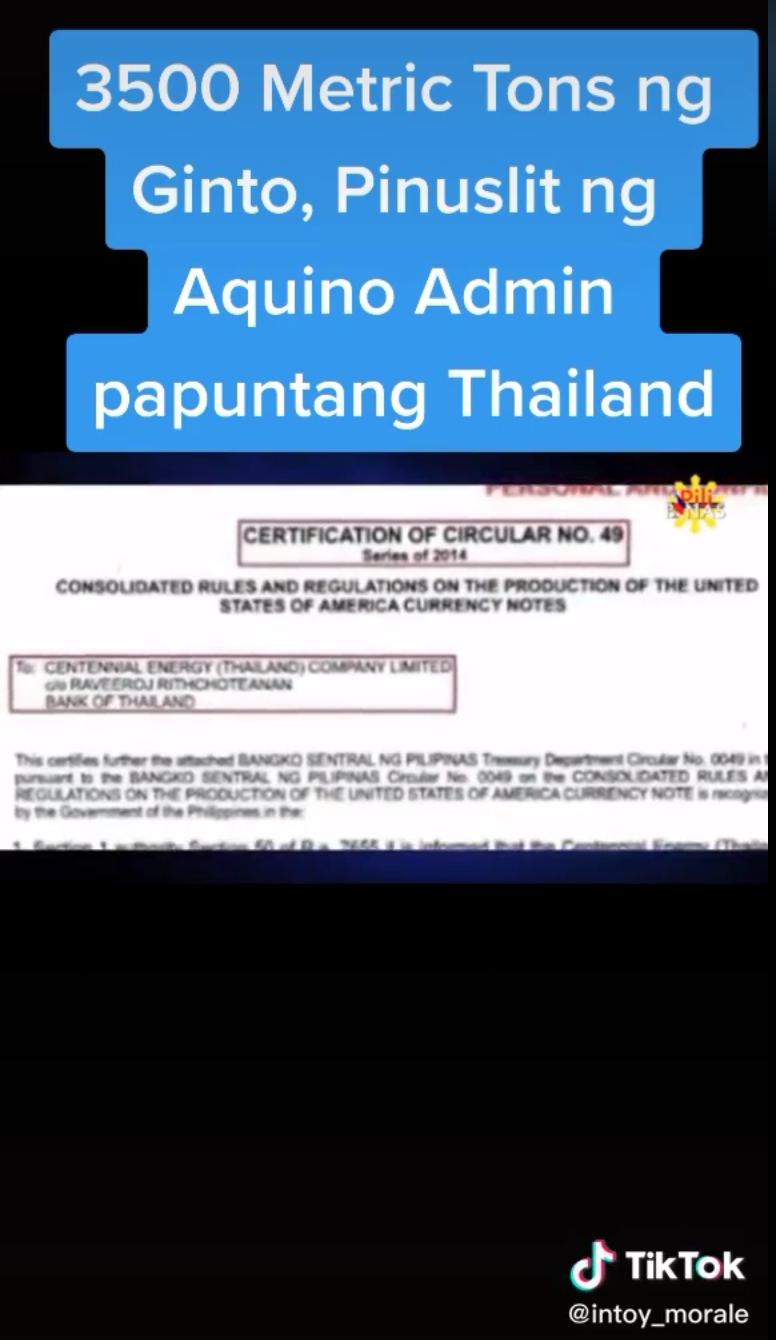

While intended for entertainment, TikTok, the sixth most used social media platform in the country, has increasingly become an avenue for disinformation.

Kristoffer Rada, TikTok head for public policy, told Rappler they “do not tolerate any kind of misinformation,” including misleading posts about elections. TikTok has partnered with news wire service Agence France-Presse (AFP) for fact checks in the Philippines.

Rada said if the content is confirmed to be false, they automatically remove it. If not, users will see a banner “informing them that the content has been reviewed but cannot be conclusively validated.” Anyone who shares it will see a prompt that the video contains unverified content.

However, there are some videos that continue to exist on the platform despite being tagged as misleading by AFP. The videos, too, could still be shared and sent to other TikTok users without any prompts.

There are also fake videos – already fact-checked on other platforms – that continue to spread on TikTok. These include the false claims that the family of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos owns millions of tons of gold that could save the Philippines and the world.

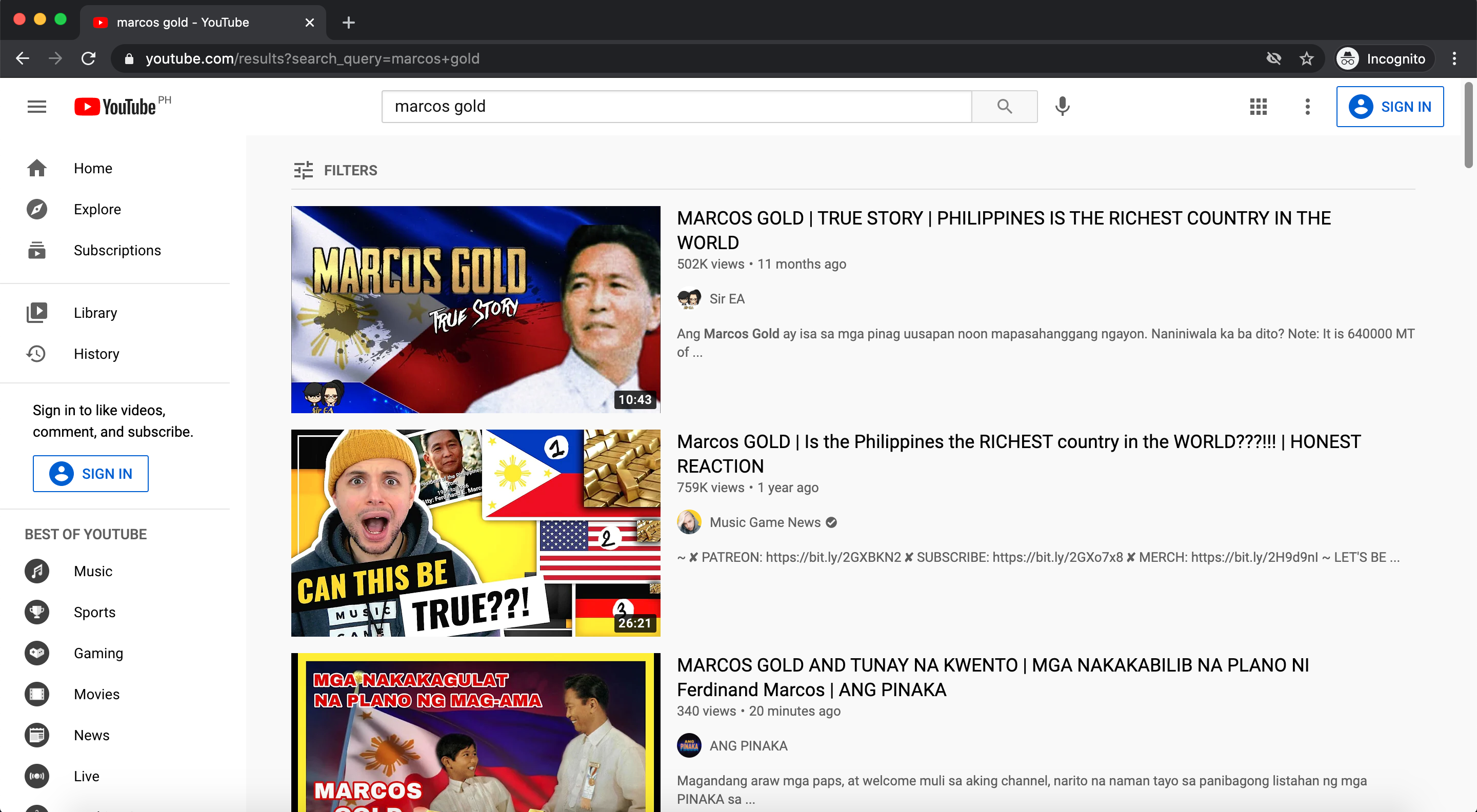

YouTube has inconsistent policies on misinformation. It has policies against election- and COVID-19-related misinformation, but its Community Guidelines do not explicitly prohibit spreading falsehoods, leaving out other possible situations where disinformation can occur. YouTube also does not label false information on its platform.

In countries like Brazil, India, and the US, users can see panels that carry relevant fact check articles when viewing a misleading or false video. The feature is not yet available in the Philippines.

While YouTube says only less than 1% of its platform’s contents is harmful, this still poses a serious threat, as YouTube beat Facebook to become the country’s top social media platform in the third quarter of 2020. (READ: YouTube’s unclear policies allow lies to thrive)

Political ads: To ban or not to ban?

With the pandemic restrictions and the shutdown of ABS-CBN, the Philippines’ largest broadcaster, potential candidates are expected to place more of their advertisement on social media. In fact, a few of them have started spending thousands to millions of pesos for Facebook advertising, according to a report by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Facebook says it will not ban political ads. This means users will see more potentially misleading and false political content, which Facebook does not allow to be fact-checked on the platform.

Instead of a ban, Facebook is working on making political advertising transparent through its Ad Library.

Political ads on the platform would now indicate who paid for them, where they ran, information on who the ads reach, and more details about the people who are running Facebook Pages – a move that the Commission on Elections welcomes.

Unlike Facebook, Twitter and TikTok have banned political ads. Twitter says it believes the reach of political message should be earned and not bought, while TikTok says paid political ads do not fit the TikTok platform experience.

But there are loopholes that could be exploited to evade this rule. In the age of influencer culture, politicians could pay individuals with huge followings to promote political agenda – whether explicitly or implicitly, without verifying the information being promoted.

On TikTok, many influencers and users have begun promoting potential candidates, with some even spreading misleading and wrong information. Rappler asked TikTok for comment on this, but they have yet to respond.

Micro-influencers, or social media users with smaller followers, could also serve as vehicles for political propaganda, as they did in the 2019 elections. Closed Facebook groups, mostly catering to overseas Filipino workers and conspiracy theorists, have also been pivotal in the spread of disinformation then.

Now, Facebook says administrators and moderators of groups that were taken down will not be able to create any new groups for a period of time.

But whether this will be strictly enforced is uncertain, as Facebook had taken down several fake and questionable accounts in the country but had been unsuccessful in ultimately ending the problem.

Election integrity, data breach

Following the US Capitol riot, social media platforms scrambled to crack down on Trump’s baseless accusations and, while mostly belatedly, to enforce stricter policies.

Trump’s Facebook and Instagram accounts were banned, but critics slammed the decision for failing to address the “deep, systemic content issues” of the platform. (READ: Facebook admits lack of policy on ‘coordinated authentic harm’ in leaked report)

Twitter permanently suspended Trump’s personal account and placed warning labels on tweets with premature election claims.

YouTube has a Presidential Election Integrity policy, where it says it removes content that promotes false claims about the outcomes of any past US election. It also removes content, accounts, and channels that can potentially interfere with democratic processes. It remains to be seen how these will be applied in the Philippines.

Previous elections also saw massive data breach, including voters’ databases and personal information, like what happened with Cambridge Analytica.

Facebook says it will continue to improve coordination with law enforcement and other technology companies to prevent both foreign and domestic meddling. Facebook also says it plans to send Filipino users notifications on how to register to vote. (READ: FAQs: What you need to know about voter registration during pandemic)

Gaps in hate speech policies

During election season, troll farms work on overdrive. Campaign teams aggressively mobilize supporters for certain candidates, like how Duterte carried out his social media campaign in 2016. Trolls also frequently use foul and demeaning language to attack critics, while state actors often post or send hateful messages against perceived enemies and critics.

Tech platforms have their own definitions of hate speech, but most fail to enforce policies against it. (READ: State-led and coordinated: ICFJ dives into online attacks vs Maria Ressa)

Twitter recently rolled out improved prompts that encourage users to reconsider wording potentially harmful or offensive tweets, but they’ve only started covering tweets in English. YouTube relies heavily on their strikes system for repeat offenders.

Facebook, for its part, says it looks into the context and intent of the posts. But a 2020 study found that Facebook often fails to effectively consider context when removing hateful content. Facebook’s reporting tool also makes it difficult to prove repeated abusive behavior, unlike in Twitter, where you can send multiple tweets as evidence.

Anti-hate organization Anti-Defamation League also says that removing hate speech “does not solve the fundamental problem of Facebook,” as its algorithms can still increase users’ exposure to hateful content.

What now?

Comelec faces a huge problem that it is still not prepared for. For now, its focus is to ensure a level playing field with the limiting of in-person campaigning.

“The challenge is to take a free platform and one that’s been maximized within the hilt of its potential by some candidates, and to make it accessible at that same level to less well-funded candidates,” Comelec spokesperson James Jimenez said in a Rappler Talk interview.

Jimenez said Comelec plans to work with tech professionals to address the issue. While tech companies are willing to help, he acknowledged that platforms ultimately have their business interests to prioritize.

“Misinformation, disinformation – these are big problems. We do plan to team up, we do plan to enter strategic partnerships with tech professionals, with industry professionals, individuals who are motivated to do their part in helping ensure clean election. We are absolutely open to partnerships with them,” he said.

Ona Caritos, executive director of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), said Facebook should continue its partnership with Comelec, election monitoring organizations, and other like-minded groups “to form a multi-stakeholder solution to ensure electoral integrity.”

“A good start is the campaign for people to understand and to use Facebook’s Ad library so that the electorate will be guided on how candidates spend online, which is a crucial aspect of electoral integrity,” said Caritos.

Ultimately, platforms “should robustly address” fake accounts through account verification. Addressing these, she said, would also eliminate “other evils,” such as cyber crimes.

“We must understand that social media platforms are in the best position to address disinformation, given the amount of resources and technology behind them,” she said.

It remains unclear though when tech companies would fix the systemic problems of their multibillion dollar platforms. For now, Filipinos watch whether tech platforms and the government have learned from mistakes that have harmed democratic processes here and globally. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.