SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

(First of 2 parts)

AT A GLANCE:

- Bongbong Marcos claims widespread cheating in Basilan, Lanao del Sur, and Maguindanao. He wants election results annulled in these provinces where Robredo won.

- Robredo argues that Marcos anchored his protest on “baseless claims.”

- Election fingerprints for the 3 provinces reflect inconsistent vote shares and voter turnouts. Not all towns and cities in these provinces show a pattern that points to possible cheating.

- There has yet to be a protest with the PET where votes for an entire town, much less a province, were nullified.

MANILA, Philippines (UPDATED) – More than a year since the 2016 national elections, the fight for the 2nd highest post in the land is far from over.

On Tuesday, July 11, the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) conducted the preliminary conference, which lays the groundwork for the resolution of the electoral protest filed by Marcos. (READ: Presidential Electoral Tribunal: What happens to a protest?)

This follows over 12 months of legal wrangling by both camps before the Supreme Court, which sits as the PET. (TIMELINE: Marcos-Robredo election case)

Second-placer former senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr is questioning the victory of Vice President Maria Leonor “Leni” Robredo. Only 263,473 votes separated Robredo and Marcos in the 6-person VP race in May 2016.

In PET Case No. 005, filed on June 29, 2016, Marcos assailed Robredo’s victory by saying, among others, that poll fraud and irregularities were present in 30 provinces and cities, covering a total of 39,221 clustered precincts, or almost half of all polling places nationwide.

In his petition, Marcos is asking for a technical examination and forensic investigation of the ballots in all 30 areas, and a judicial revision or recount of votes in 27 of them. (READ: Presidential Electoral Tribunal: What happens to a protest?)

He also seeks the annulment of election results in the remaining 3 provinces – Basilan, Lanao del Sur, and Maguindanao – all in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) – due to the “widespread presence of terrorism, violence, threats, coercion, force, intimidation” and other anomalies such as batch-feeding and pre-shading of ballots.

Robredo placed first in these areas – consisting of 2,756 clustered precincts – and garnered a total of 477,985 votes, compared to Marcos’ 169,160 votes.

Allegations

Among the incidents Marcos cited in his protest were those in Datu Saudi Ampatuan, Maguindanao.

In a news report, witness Normina Taha claimed to have seen acts of intimidation and the pre-shading of ballots in a school within the area, allegedly “to ensure the victory of the full slate of the Liberal Party (LP) in the said polling place.” She said a group employed by reelectionist mayor Samsudin Dimaukom were the ones intimidating the voters.

Meanwhile, defeated vice-mayoral candidate Bassir Utto also claimed witnessing similar acts of intimidation allegedly committed by armed men employed by a certain Wahid Tundok. Tundok is the leader of the 118th Base Command of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Both Taha and Utto are listed as witnesses in Marcos’ preliminary conference brief.

Marcos also cited other incidents of irregularities in Basilan and Lanao del Sur such as alleged pre-shading of ballots, a suspicious high voter turnout, voter intimidation, and minors casting votes in some precincts.

Robredo’s response

Responding to Marcos’ election protest, Vice President Robredo filed a 536-page answer and a counter-protest.

Robredo said that Marcos’ protest is founded on “baseless claims.” Robredo also assailed the Marcos camp for not appending relevant admissible documentary evidence and for relying heavily on affidavits of his supporters.

She also noted that incidents cited by the Marcos camp in his protest were not recorded in the minutes of voting for the concerned precincts. Minutes of voting (MOVs) are documents filled out by officials manning the precincts on election day.

Rappler checked available MOVs for Datu Saudi Ampatuan and noted that while some precincts reported the replacement of problematic vote-counting machines, no reports of violence or other untoward incidents were logged.

This does not necessarily mean that no irregularities happened. According to election lawyer Rona Caritos of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (Lente), parties to a protest will need to provide other evidence to substantiate claims of irregularities.

“This could probably be testimonial evidence through affidavits of watchers, or documentary evidence like pictures or video,” Caritos said.

The Robredo camp also questioned the credibility of Marcos’ witnesses in her response.

For instance, Robredo pointed out that Taha “is the team leader of the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan” in Datu Saudi Ampatuan town. KBL is the party of Marcos’ father, former president Ferdinand Marcos.

Robredo also noted that Utto “was eerily silent on why he did not even bother to inform the mayoralty candidate or the other members of his slate” in the United Nationalist Alliance (UNA).

What election results data say

With an election this close, allegations of poll fraud, and a protest covering many areas, can the data help support the allegations of the Marcos camp?

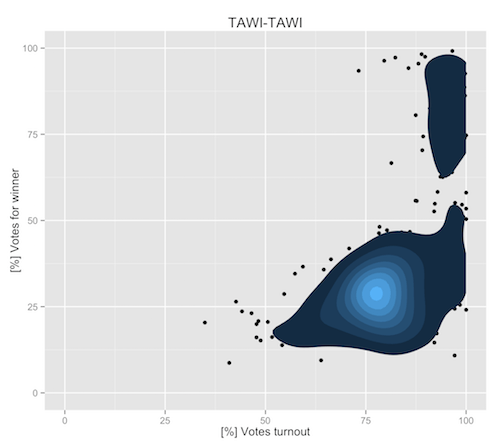

One way to check is through the “election fingerprint” of voting results in the protested areas. This refers to traces of possible poll fraud that may have been left in the voting data.

By plotting voter turnout against votes received by the winner, possible cheating can be “detected” – that is, when there are dots that “cluster” at, or cluster near, the upper right portion of the charts.

This indicates an unusually high number of voters turning up in precincts to give more (if not all) votes to the winner.

The “fingerprint” chart is patterned after the results of a 2012 study by a group of researchers from the Santa Fe Institute in the United States. (READ: ‘Fingerprints of election thieves’ spotted in past PH polls data)

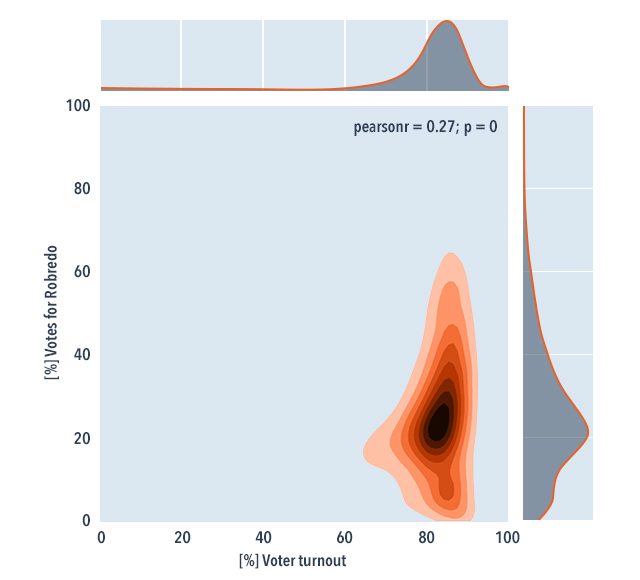

Here is the election fingerprint for the votes received nationwide by Robredo in the 2016 vice presidential race. Notice that the points are concentrated near the bottom right.

This means that in general, she received a fair share of votes and that turnout in most precincts are within the national voter turnout rate of 82%.

Then, see the charts below for the 3 ARMM provinces (Basilan, Lanao del Sur, and Maguindanao) whose votes the Marcos camp wants nullified. For comparison, the fingerprints for Metro Manila and the top 2 vote-rich provinces, Cebu and Cavite, can also be seen below.

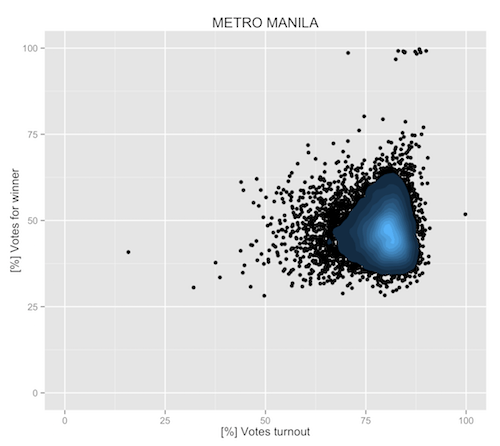

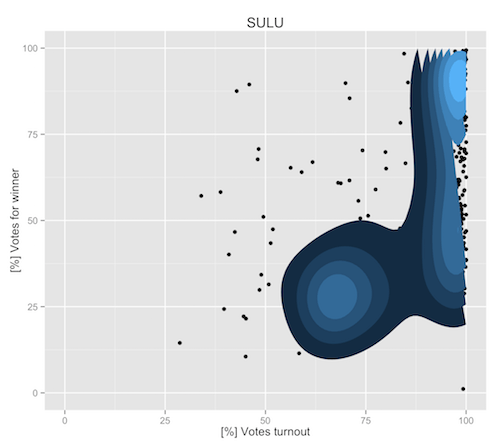

Notice that the ARMM provinces exhibit distinct fingerprints.

These indicate that some precincts reflected a nearly 100% voter turnout, but the range also went as low as around 40%, as evidenced by the wide horizontal space taken up by the blobs representing the precincts.

A 100% turnout is highly unlikely, but it has been recorded in 116 precincts in 2016, most of which are in ARMM. Take note, however, that this is just around 0.1% of 92,509 clustered precincts nationwide.

The ARMM graphs also show wide and varying vote shares between around 10% and 100% for the winner – unlike the graphs for vote-rich provinces, where the percentage of votes was concentrated between about 25% and 75%.

This shows inconsistency in the ARMM results, where the winner gets all votes in some precincts, then next to none in others. In the 2016 polls in ARMM, Robredo got 0 votes in at least 53 precincts, and Marcos in 95 precincts.

This pattern for the 3 ARMM provinces is similar to the other two provinces in the region, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. Marcos won in Sulu, while Robredo won in Tawi-Tawi.

This is not the first time election data from the ARMM provinces has exhibited these same patterns.

|

|

History of poll fraud

The ARMM has had a history of poll irregularities and election-related violence.

The region was a hotbed for private armed groups, maintained by or identified with politicians, in the 2013 polls. Election watchdogs like the Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV) reported at least 51 violent incidents nationwide in the 2016 polls, with a number of these taking place in ARMM.

The region usually favored the candidates of the ruling party. But much has also changed.

In 2004, for instance, actor Fernando Poe Jr, who ran against then reelectionist president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, failed to get a single vote in many towns in Maguindanao, then ruled by the powerful Ampatuan family. In the 2007 midterm elections, the Ampatuan clan delivered a 12-0 sweep in Maguindanao in favor of Arroyo’s Senate slate. As a consequence, many prominent national candidates got zero votes in the entire province that year.

In 2010, opposition candidate Benigno Aquino III won the presidential race in the entire ARMM, but his running mate, Mar Roxas, lost. Jejomar Binay of UNA won the vice presidential race in the region that year.

In the 2013 midterm polls, only 9 members of Team PNoy (Aquino’s Senate slate) made it to the region’s top 12. Binay’s daughter Nancy even topped the Senate race in ARMM.

The 2016 senatorial race in Maguindanao likewise didn’t reflect a repeat of the 12-0 sweep, with only 7 candidates backed by the outgoing administration winning there.

Per town, city

When we drill down to the town and city levels, not all fingerprints exhibit the same pattern as the provinces’ fingerprints.

See the election fingerprints for the votes received by Robredo and Marcos in Basilan, Lanao del Sur, and Maguindanao in the spreadsheets below. Numbers in each cell indicate the number of clustered precincts in a voter turnout range (e.g. 50%-59%) where a candidate received a certain percentage of votes. The darker the shade of the cell, the bigger the number of precincts.

Fingerprints for all ARMM provinces can be also be viewed. Winners for president and vice president in each town are listed in another tab. Data is from the Comelec Transparency Server.

Not all towns in the 3 provinces exhibited the distinctive mark associated with cheating (or points lumping at or near the upper right corner of the chart for the winner).

Marcos specifically mentioned these towns in his protest (shaded orange in the spreadsheet above):

- Basilan – Akbar, Al-Barka, Hadji Mohammad Ajul, Lamitan City, Lantawan, Sumisip, Tabuan-Lasa, and Tuburan

- Lanao del Sur – Bacolod-Kalawi, Lumbaca-Unayan, Marawi City, and Pagayawan

- Maguindanao – Datu Saudi Ampatuan

Robredo won in all these towns, except in one (Hadji Mohammad Ajul, Basilan) where Marcos prevailed.

In Basilan, fingerprints for Hadji Mohammad Ajul, Lantawan, and Tabuan-Lasa did not display such pattern.

The fingerprint for Datu Saudi Ampatuan also did not show the same distinctive mark. The same goes for the 4 Lanao del Sur towns. These appear to indicate that there are not enough precincts to support claims of widespread cheating in these towns.

Lawyer Vic Rodriguez, counsel and spokesperson of Marcos, reserved comment on the election fingerprints. “But we have those graphs, we have it. At doon kitang-kita ‘yung totoong nangyari at ‘yung pinuwersa nilang mangyari,“ he told Rappler. (We can see there what really happened, and what they forced to happen.)

The camp of Robredo did not respond to our queries on the fingerprints.

Is nullification possible?

In her verified response, Robredo said the incidents that Marcos included in his protest were “not enough” to nullify the results in an entire province.

Lawyer Bernadette Sardillo of the Robredo camp, in an email to Rappler, said that the protestant must show that “more than 50% of the votes cast were affected by violence, threats, intimidation and fraud during the elections.”

This is also mentioned in Robredo’s verified answer, citing the Abayon v. House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal ruling of the Supreme Court.

Asked about this, Rodriguez said, “That’s their problem. We have our own sets of proof and legal strategy to present before the PET. And we’re confident in our case.”

He also questioned Robredo’s victory in ARMM, saying that it couldn’t have been her bailiwick. “This was her first time to foray in a national election. So, all of her reasoning, or that of her group, has a total disconnect with reality,” he said in a mix of English and Filipino.

As for allegations pertaining to terrorism and vote-buying, the Robredo camp said in their preliminary conference brief that there is “no allegation” that the Vice President “was involved or participated in or had any knowledge of the alleged electoral fraud, anomalies, or irregularities… in the election protest.”

Asked about the possibility that the LP was behind these incidents, Sardillo told Rappler, “There is no allegation in the protest that the Liberal Party is behind it.”

But Rodriguez maintained that these incidents still happened. “Regardless of whether she knows it personally or not, who is the beneficiary? So you mean to say, nagnakaw ka, eh ‘yung fruits, binigay mo sa akin. Absuwelto na ako nun?” (You stole, and you gave the fruits to me. Am I absolved?)

Finally, Rodriguez mentioned a “late surge” of votes for Robredo hours after polls closed on May 9.

This “cheating pattern” allegation had been explained and debunked, however, in multiple data analyses and simulations by statisticians and experts. (READ: Leni ‘stole’ the vice presidency? The data doesn’t say so)

Unprecedented

Ultimately, said Lente’s Caritos, “There are a lot of scenarios, but to nullify the votes in the 3 provinces, that would be somewhat difficult. It’s possible, but difficult.”

Caritos added, “He can invalidate a number of the votes based on affidavits – for example, a certain polling place – but not all of the province.”

She mentioned a discussion on the annulment of votes in the decision of the Senate Electoral Tribunal (SET) in Pimentel vs. Zubiri in 2011.

Senator Aquilino Pimentel III, then a candidate, sought the annulment of votes in the 2007 senatorial elections in the town of Sultan Kudarat in Maguindanao.

The SET argued that if it would grant his request, it would come “with a heavy consequence – the disenfranchisement of many innocent voters.” Instead, the SET “painstakingly endeavored to ‘distinguish what votes are lawful and what are unlawful’.”

Caritos also pointed out the high accuracy rate of the 2016 polls, which stood at 99.9027% based on the random manual audit (RMA) of voting machines.

The RMA compares the election results as counted by vote-counting machines against the manual audit of ballots in randomly-selected clustered precincts to check for any variance or difference between the two.

The accuracy rate for the vice presidential race was 99.8976%. Meanwhile, the VP race in ARMM had an accuracy rate of 99.9342%.

These are based on the report of the Random Manual Audit Committee, composed of the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel), the Comelec, and the Philippine Statistics Authority.

At the end of the day, said Caritos, “it’s the PET that would decide on the case, on the strength of the evidence.” – Michael Bueza, Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza, and visualizations by Russell Shepherd and Wayne Manuel/Rappler.com

(To be concluded in Part 2: The Marcos and Robredo camps have each identified 3 provinces that would support their prayer that a recount is necessary in 27 areas for Marcos, and in 13 areas for Robredo. How does the “election fingerprint” in these areas look like?)Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.