SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

PART 1

MANILA, Philippines – The sprawling quadrangle of the Cayetano Arellano High School lies a few blocks away from Tondo, where the first death in President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war happened.

Many of the high school students here have not only seen the war on drugs from their television screens; they live in the very same communities where men and women have been gunned down under suspicions of drug use.

The students are afraid, said Arellano High School health teacher Leah Olmos.

“Meron silang takot ‘yong iba, especially ‘yong mga nakatira sa Tondo. Kasi no’ng diniscuss namin ‘yong drug scenario, they really shared that sometimes [sa] gabi, minsan nakakarinig sila ng putok nga,” she said.

(Some are scared, especially those living in Tondo. Because when we discussed the drug scenario, they shared that sometimes they would hear gunshots at night.)

Luckily, none of the 4,300 Arellano High School students have relatives victimized by the bloody drug war.

Such an atmosphere, however, only highlights the crucial role schools play in being the frontline defense of students against illegal substance abuse.

The Department of Education (DepEd) designed the Kindergarten to 12 (K-12) curriculum in such a way that students would learn about “Substance Use and Abuse” in their health classes in Grades 5, 8, and 9.

But old and new problems persist: There’s the perennial issue of inadequate textbooks for students and schools without proper audio-visual equipment for lessons. Under the Duterte administration, teachers are now confronted by students with questions about the drug war.

What do schools teach to these inquisitive students, and are the lessons enough to prevent the children from using the drugs themselves?

Inside the classroom

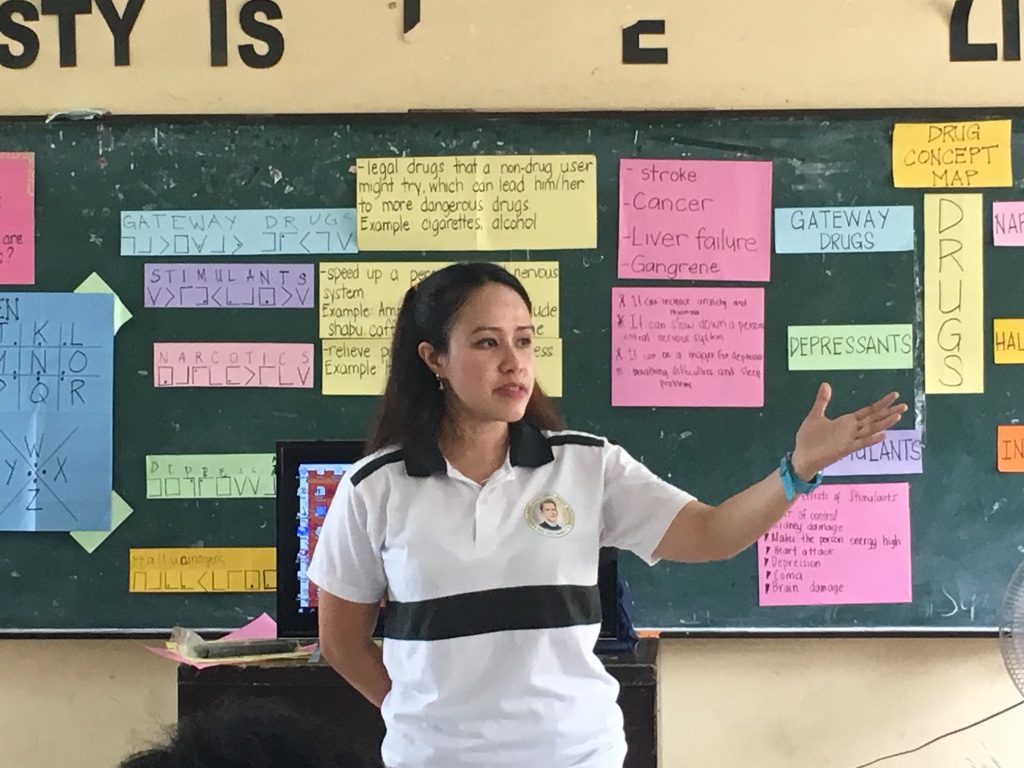

Rappler had the chance to sit in during the health class of Arellano High School’s Grade 9 Abad Santos section.

It was the middle of the day, the classroom humid. Olmos started setting up her things while waiting for her students to enter the classroom. She placed a 32-inch television screen in front. It was hers, bought with help from her sister’s credit card. The longtime teacher said the school couldn’t afford to provide television screens or projectors in each classroom, so she improvised.

She also carried a tablet that contains her lesson plan for the day. Olmos got the gadget for free from Manila Mayor Joseph Estrada, who gave them to teachers in his city.

When the students finally settled in the classroom, Olmos told them their topic was about the different types of drugs: gateway drugs like cigarettes and alcohol, stimulants, narcotics, inhalants, depressants, and hallucinogens.

She made the students watch a 10-minute video explaining why some Filipinos end up selling and using drugs. Poverty was the main cause. Then came a post-video debriefing, where Olmos asked the children guide questions about the short video.

The teacher also raised the question if her students knew about the government’s drug campaign. One student said yes, adding that some Filipino teenagers were killed because they were suspected to be drug addicts. (READ: LIST: Minors, college students killed in Duterte’s drug war)

Do these teenagers know about the effects of drugs? No, said another student. That’s why he and his classmates should stay away from illegal substances.

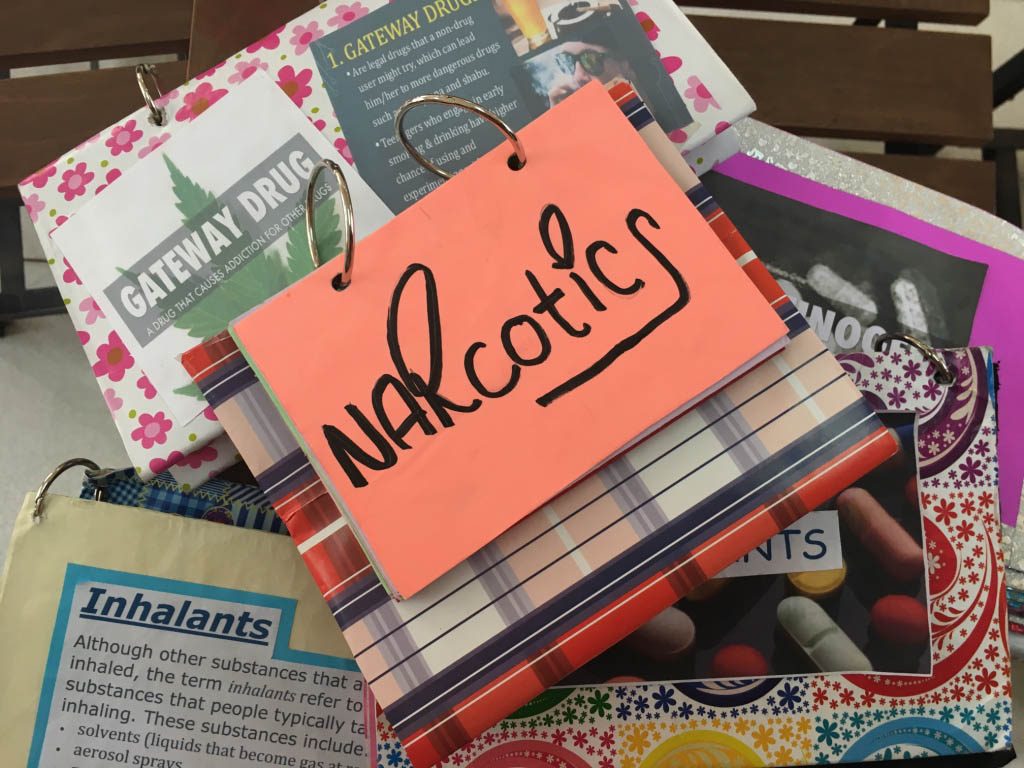

The class was then separated into 6 groups, each assigned to decode a word that Olmos wrote in strips of cartolina. The words corresponded to one of the 6 types of drugs.

The teacher then asked them to bring out their art materials and make a scrapbook about the kind of drug assigned to them. Out came the pens, glue, sequins, and wrapping papers, with the students scrambling to finish their masterpieces within the teachers’ timeframe.

The result was 6 colorful scrapbooks that described the 6 types of drugs in detail – from their proper use in the medical community, who uses them, and the drugs’ effects on the body when abused.

At the end of the lesson, Olmos gave her students homework: interview someone from their community about the different myths and misconceptions about drug use and abuse. Give the signs and symptoms of drug addiction.

Information vs ignorance

Under the K-12 curriculum, the topic “Substance Use and Abuse” is covered by Grades 5, 8, and 9 students during the 3rd quarter of the school year (SY).

Olmos said she begins the lesson with a quick discussion on the current drug scenario in the Philippines.

“According to our discussions, they are aware that those involved in drugs are getting younger and younger. We then discuss the factors. What are drugs? Do they have positive effects? Do they have negative effects? And then after that are the prevention skills. How are they going to say no if somebody is asking them to take it?” said Olmos.

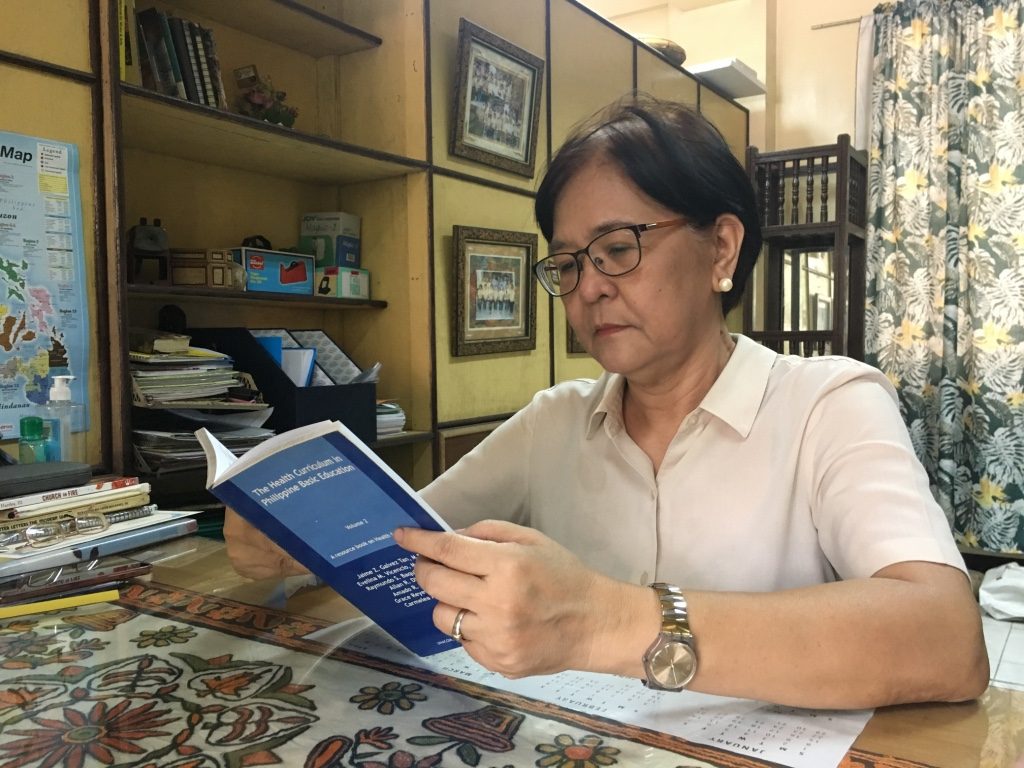

Carol Manalaysay, Arellano High School’s head teacher for its music, art, physical education, and health classes (MAPEH), said they also do not hesitate in teaching the students about the different street names of the drugs.

“We don’t want to teach the value of ignorance, because it’s there. You have to be informed. If you don’t give the information, it’s there and they don’t know about it, we’re teaching ignorance. We don’t want to produce youth who [are] unaware,” said Manalaysay in Filipino.

“Drugs are everywhere. If we’re not going to [correct] the information about it, there will be more curiosity. We’re here, as teachers, we’re here to inform,” she added.

Arellano High School also holds parent-teacher conferences and seminars for parents, where preventing the abuse of illegal drugs is discussed. (READ: In a time of ‘pervasive’ violence, build ‘caring communities’ for children)

Manalaysay said parents’ involvement is important, because students who end up getting addicted to drugs or alcohol often come from broken homes.

“Oftentimes ‘pag tinanong namin ang bata bakit kayo nag-inuman sa Luneta, ‘pag tinanong namin, parents aren’t around, parents working, parents are separated… Ang scenario there is still, nangyayari ang mga drug-related problems kasi parang ang tingin ko, nadi-dysfunction ‘yong family,” said Manalaysay.

(Oftentimes when you ask a child why they went drinking in Luneta, they would say parents aren’t around, parents working, parents are separated. The scenario is that drug-related problems happen because, I think, the family is dysfunctional.)

Manalaysay said this is why she would always remind teachers to check in on the home life of their students, too.

No guidelines on drug war discussions

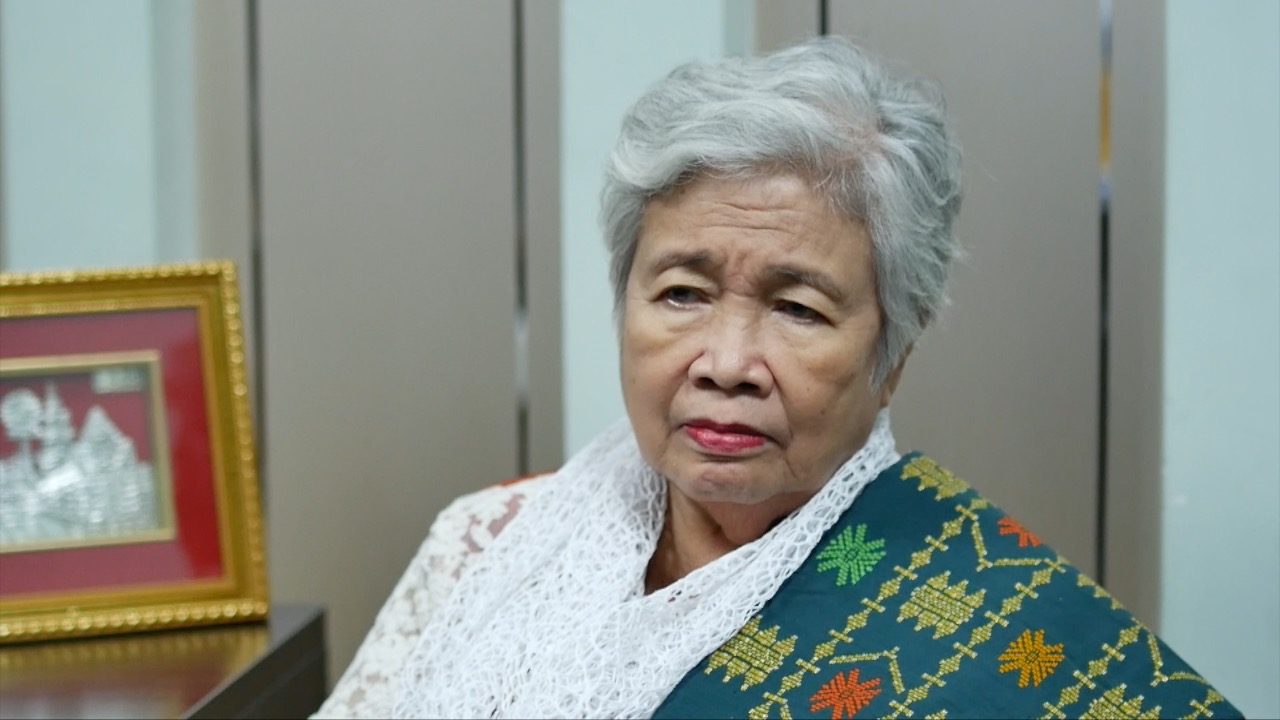

In 2016, Education Secretary Leonor Briones already announced her plan to make drug education classes go beyond textbooks in teaching the dangers of drug abuse in the country.

Briones believes students would better understand real life stories on drug addiction and rehabilitation if these were shown to them through school films, plays, and dramas.

Still, there’s a glaring hole in the drug education curriculum: DepEd has no directive to schools to dedicate substantive discussions to explain and give perspective to what is happening in the government’s anti-drug campaign.

At most, teachers like Olmos breeze through the said topic in class, then shift the focus on the more “academic” side instead: description, types, positive and negative effects of illegal drugs.

Briones admits this shortcoming.

“Right now, [we have no directives]. Thank you for giving us that feedback. We will consider that seriously for places where the drug menace is most intense,” said Briones.

The Cabinet official added that this is yet another reason for supporting DepEd’s plan to conduct mandatory drug testing of high school students this SY.

“And also this is also why instituting our drug testing program [is important], precisely to determine the prevalence and the dangers. That is a very real concern. If I were living in some of these places, my parents or myself would really be terribly scared,” said Briones.

DepEd, however, is already receiving flak over the drug testing, with critics arguing the plan would expose minors to the dangers of Duterte’s drug war. Briones thinks otherwise. (READ: Duterte OKs random drug testing of HS students – Briones)

Grade 9 student Angelo Guballo wishes the drug war will be a permanent topic in class. He said this is because most of his classmates are shy to bring up the matter to their teachers.

“Gusto ko rin po ma-discuss ‘yong war on drugs para po malaman din po ng mga iba kong kamag-aral, iba kong schoolmates po dito kung ano po ‘yong nangyayari sa kapaligiran natin. Kasi hindi po lahat ng bata may kakayahang malaman ‘yong nasa paligid nila,” he said.

(I want us to discuss the war on drugs so that my schoolmates would know what’s really happening in our communities. Because not all kids have the capacity to properly understand what’s going on around them.)

Olmos said that in the cases when a student approaches her to ask about the drug war, she aims to give an objective answer, avoiding imposing a judgment on her students.

“So sinasabi ko na according to law, everybody should have due process. So hindi ka puwede na basta-basta na bigyan ng parusa nang walang pinagdaanan na process or investigation. So kung meron man silang kakilala na napatay or something, tingnan nila kung nando’n ba ‘yon sa drug list, nabigyan ba siya ng warning or nakausap ba sila, or baka naman hindi rin pulis ‘yong pumatay,” said Olmos.

(So I tell them that according to law, everybody should have due process. So you can’t just impose punishment on someone without the proper process or investigation. If they know someone killed, they should check if the person was on the drug list, if he or she was given a warning or was spoken to, or it’s possible it wasn’t the police responsible for the death.)

Tablets to address lack of textbooks?

Another problem for drug education in the Philippines is the lack of textbooks.

Data from DepED shows only 223,481 MAPEH books were produced for 1,609,838 Grade 8 students in school year (SY) 2016-2017. The same set of textbooks are being used by Grade 8 students in the current year.

It’s the same story for Grade 9. Last SY, only 209,961 textbooks were produced for 1,467,669 students nationwide.

Meanwhile, the MAPEH textbooks of Grade 5 students for SY 2016-2017 were delivered late. So even if 2,477,000 books were enough for the 2,355,863 Grade 5 students, they were able to use their MAPEH books only at the latter part of the year.

“We don’t deny that, that there is a shortage. And it’s one of the major challenges right now,” conceded Briones.

The DepEd chief said they are now considering using tablets in schools instead of textbooks, a proposal that is backed by the President himself.

“A tablet can be kept in school – more for problem-solving, for reading, for sharing. They can be kept in school so the child goes home to be with his family, to be with his parents, instead of the lola (grandmother) helping with the homework and helping the child,” said Briones.

She agreed, however, that funding these tablets will be a “main roadblock”, considering that one tablet costs more than a textbook.

“So we are hoping that at the rate tablets are being produced and at the rate other countries are also buying other tablets, baka bababa ang presyo (the price will go down),” said Briones.

Molding self-aware students

Manalaysay is also hoping DepEd would not only restrict drug education to Grades 5, 8, and 9.

While she understands that 14- or 15-year-olds are regarded as the ones more vulnerable to drug abuse, Manalaysay thinks being able to teach children from other grade levels about the subject will be a better deterrent against drug abuse.

“Ibalik ‘yong by year level ay may drug education concepts. Kasi sa dami ng mga curriculum concepts, particularly sa MAPEH namin, nabawasan [‘yong sa drug education] eh,” said Manalaysay.

(They should bring back the curriculum where every year level is taught drug education concepts. Because of the many curriculum concepts we have to discuss in MAPEH, the ones on drug education are reduced.)

For now, schools make do with what they have. The main goal of teachers at the end of the quarter is to help students develop values that would lead them to voluntarily say no to drugs.

“So ‘yon ‘yong process ng K-12 ngayon – na hindi ‘yong teacher ang nagsasabi ng dapat mong gawin, kung ‘di the teacher will facilitate your learning na ikaw mismo makaka-process ng tamang decision. [Dapat masabi nang bata na] dahil sa napag-aralan namin ‘to, ito ‘yong mga mangyayari, ito ‘yong mga dapat na gawin, and then therefore, I will decide not to use or abuse drugs,” she said.

(So that’s the process of K-12 now – the teacher will not tell you what you ought to do, but the teacher will facilitate your learning so that you will be able to process the information and determine the right decision. The child should be able to say that we studied this, these are what will happen, this is what should be done, and then therefore, I will decide not to use or abuse drugs.) – Rappler.com

Part 2: From guns to blackboards: Police officers teach kids vs drug abuse

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.