SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

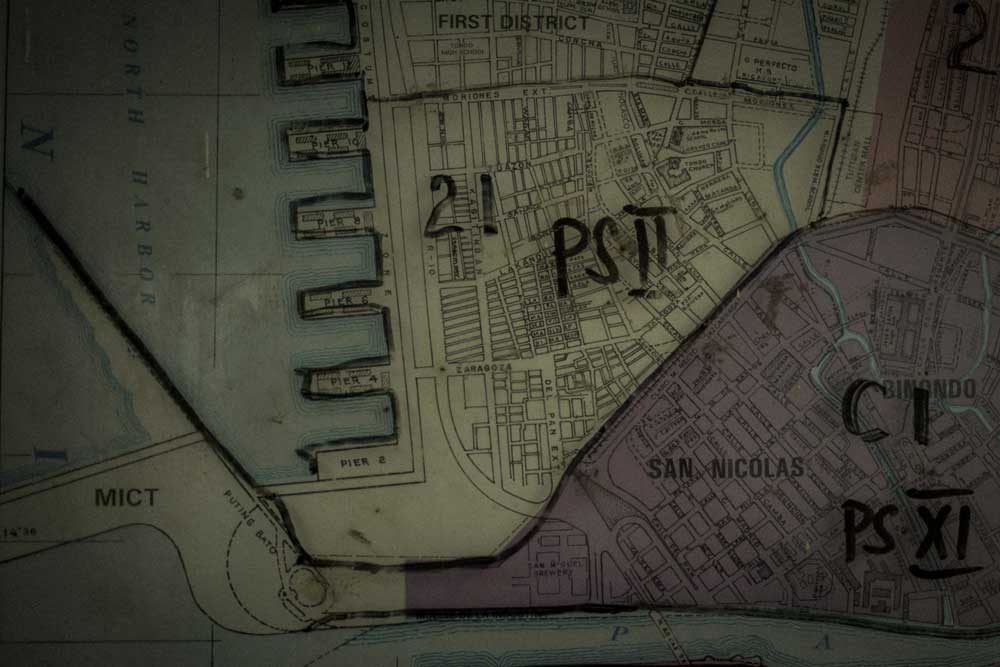

Rappler tracks the killings in Police Station 2-Moriones in Tondo, Manila, where the first drug fatality after Rodrigo Duterte’s inauguration was shot in the early hours of July 1, 2016. Of the 2,555 drug suspects killed across the country in the first 7 months of the drug war, PS-2 Moriones claims at least 45. They were allegedly killed after police were forced into shootouts. At least 13 remain unidentified in police records.

Rappler conducted more than 40 interviews in the course of a 3-month investigation. Among them are the 7 who put their names and testimonies on the record, calling 4 of the alleged encounters summary executions and accusing the police of torture and harassment. This multimedia report presents police records and witness testimonies to profile the man residents call the demon of Delpan.

The people of the villages know the killer by name.

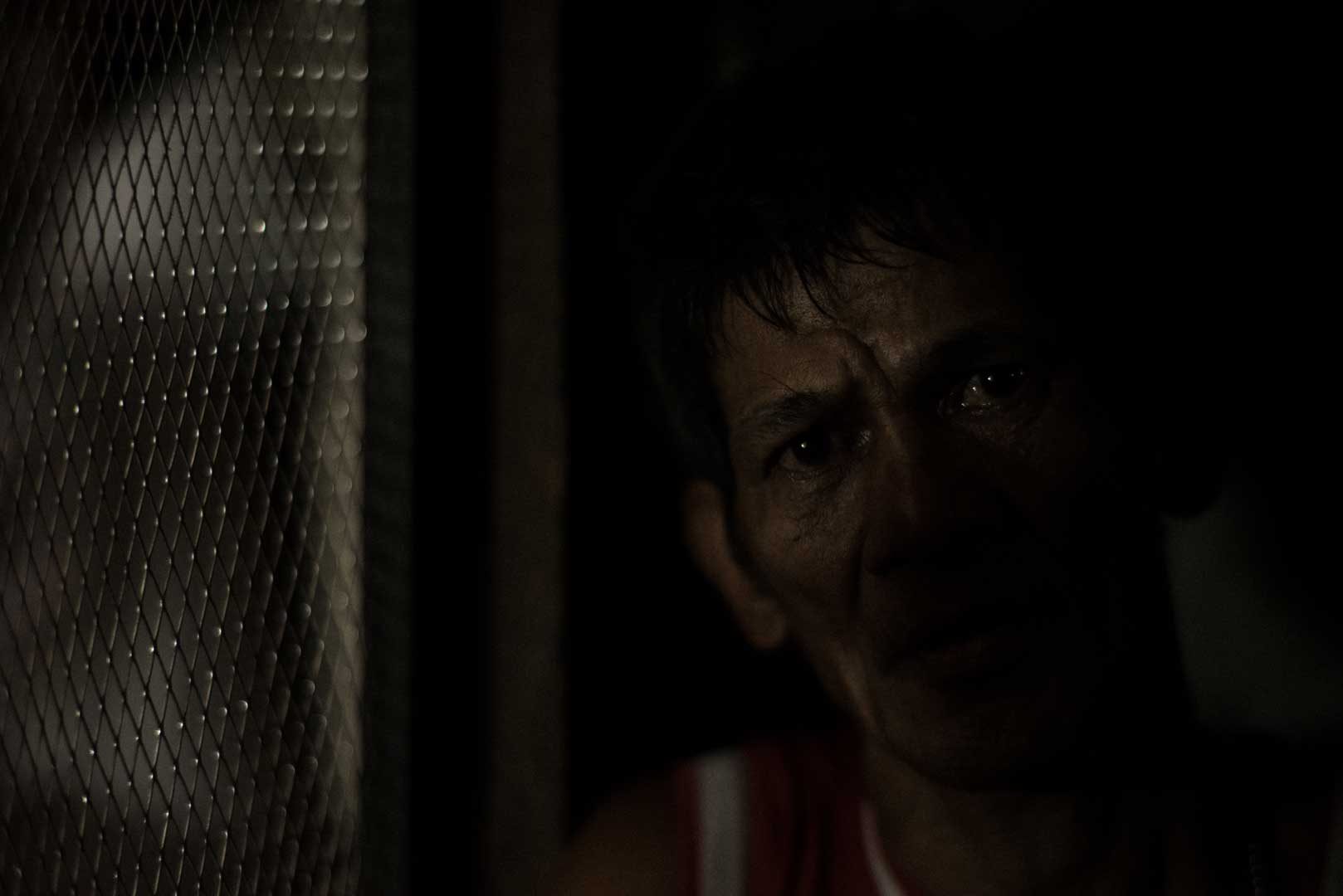

Rex’s mother knows. She remembers the night he came looking for her son, when the killer shoved her so hard the baby she held nearly fell out of her arms.

Joshua’s mother knows. She knows because he had a gun to her mouth. She knows who the killer is, knows enough that on the day her son was buried, she took a jeep and howled his name when it trundled past the police precinct.

You son of a bitch, she screamed. You killer, you killed my son.

Mario’s brother knows. His friends saw the killer drag Mario into the precinct and watched as he was beaten bloody. Mario’s brother counted the bullet wounds himself. There were 7 in all.

Danilo’s aunt knows for sure. She says it was the killer who gave her his name.

They say the man who killed Joshua and Rex and Mario and Danilo was not in uniform; neither were the armed men who were with him. But the mothers are certain the killer was a cop. The neighbors are certain the killer was a cop. Every witness to the 4 deaths is certain the killer was a cop.

There is no doubt on that one point. The cops also say the killer was a cop.

Part 1 ‘I will kill you’

On June 30, 2016, a few hours after he took his oath of office, the 16th President of the Republic of the Philippines appeared at the Delpan Sports Complex along Road 10 in Tondo, Manila to inform his new constituency that a war was at hand.

“I am asking you, do not go [into drugs] because I will kill you,” Rodrigo Duterte told the residents of Isla Puting Bato. “It may not be tonight, it may not be tomorrow, but in 6 years, there will be one day that you will make a mistake and I will go after you.”

Delpan sits at the bottom of Tondo, population 630,363, one of the capital’s poorest areas where the shanties sit cheek to jowl with slaughterhouses and churches. Plastic tables covered with white tablecloths were scattered across the orange-painted gym. Duterte’s people called the event a solidarity dinner.

President Rodrigo Duterte was late, held up by his first Cabinet meeting. When he arrived, the pineapple silk shirt was gone, traded for a striped polo shirt and a navy jacket with the sleeves rolled up. He said he ran for the presidency because he saw the Philippines drowning in drugs, criminality and poverty.

“If someone’s child is an addict,” he told the crowd, “be the one to kill them, so it won’t be so painful [to their parents].”

Do it first, he said, because that person will die either way.

“Those of you into drugs, I’m done warning after the election,” he said. “Whatever happens to you, all of you listen, it could be your sibling, it could be your spouse, it could be your friend, your child, I am letting you know, there will be no blaming here. I told you to stop. Now, if anything happens to them, they wanted it. They wanted it.”

The President’s promise was kept. At 3 in the morning of July 1, hours after the President’s speech, the earliest reported extrajudicial killing of the new regime occurred along IBP Road, near the corner of Road 10 and the Delpan Sports Complex.

The killing held the rough elements of what would be a pattern of deaths across the rest of the country in the next 7 months. Blotter number 1675 noted the “body found” of “a male person alleged victim of summary execution.” The unidentified victim, between 25-30 years old, about 5’3 tall, had been left with a sheet of cardboard over his body. It read, “I am a Chinese Drug Lord.”

The responding officers were members of the Delpan Police Community Precinct (Delpan PCP), one of 4 precincts under Manila Police Station-2 Moriones (PS-2).

At least 3 more drug-related killings committed by unidentified men would occur under PS-2’s area of responsibility within the next two weeks. They were later reclassified as deaths under investigation.

And then the police killings began. By the time the war was suspended on its seventh month, a total of 2,555 were killed across the country in what the government now calls legitimate police operations.

Part 2: ‘Good job’

Jimmy Walker got his last name from his American grandfather and not much else. Just past 20, he is snaggletoothed and shy, all elbows and collarbones inside the loose white shirt, his strawberry blonde hair already showing dark roots.

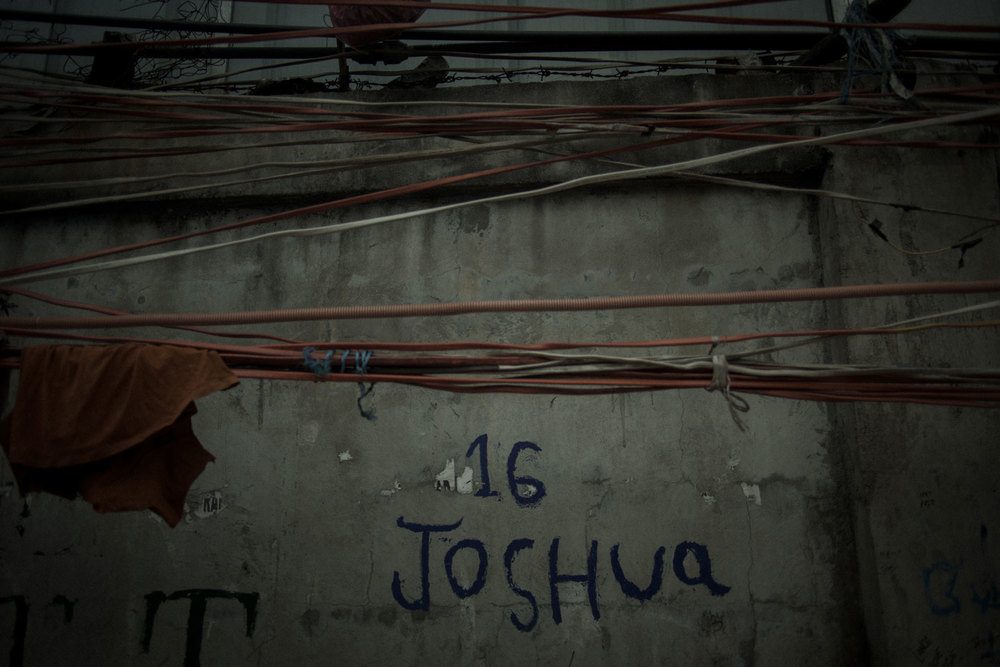

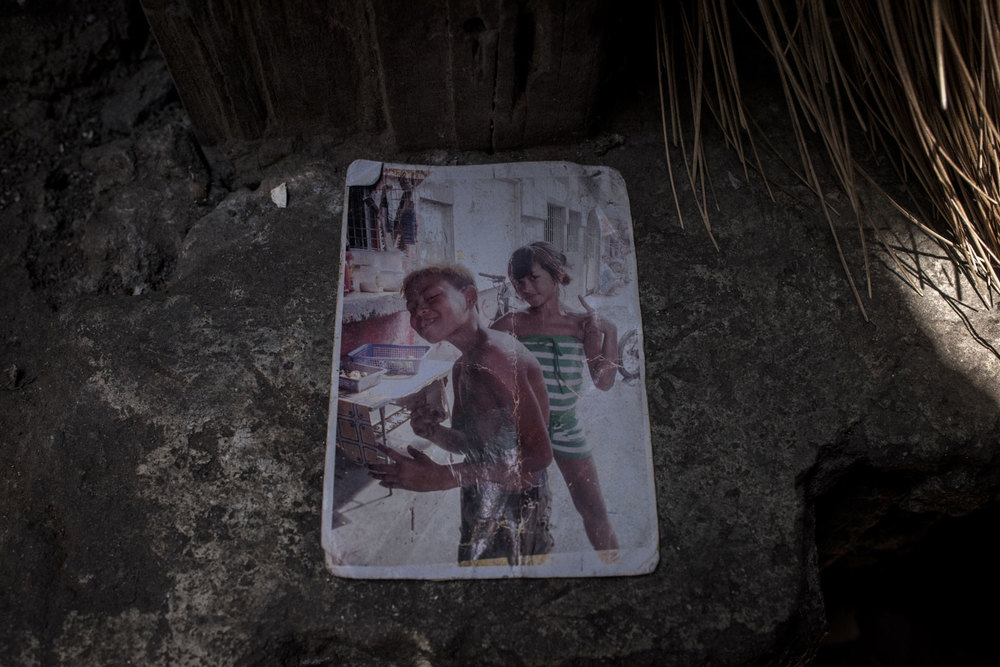

He was close to his cousin Joshua Cumilang, the 18-year-old whose family nicknamed Wawa. Joshua sniffed solvent occasionally. Jimmy, who had bad lungs, never did. The boys were as good as brothers, even if Jimmy was often the butt of Joshua’s jokes. “Jimmy, bungi,” Joshua called him. Jimmy the toothless. But it was Joshua who loaned Jimmy clothes, who fed Jimmy when Jimmy was so broke he couldn’t afford a cup of rice.

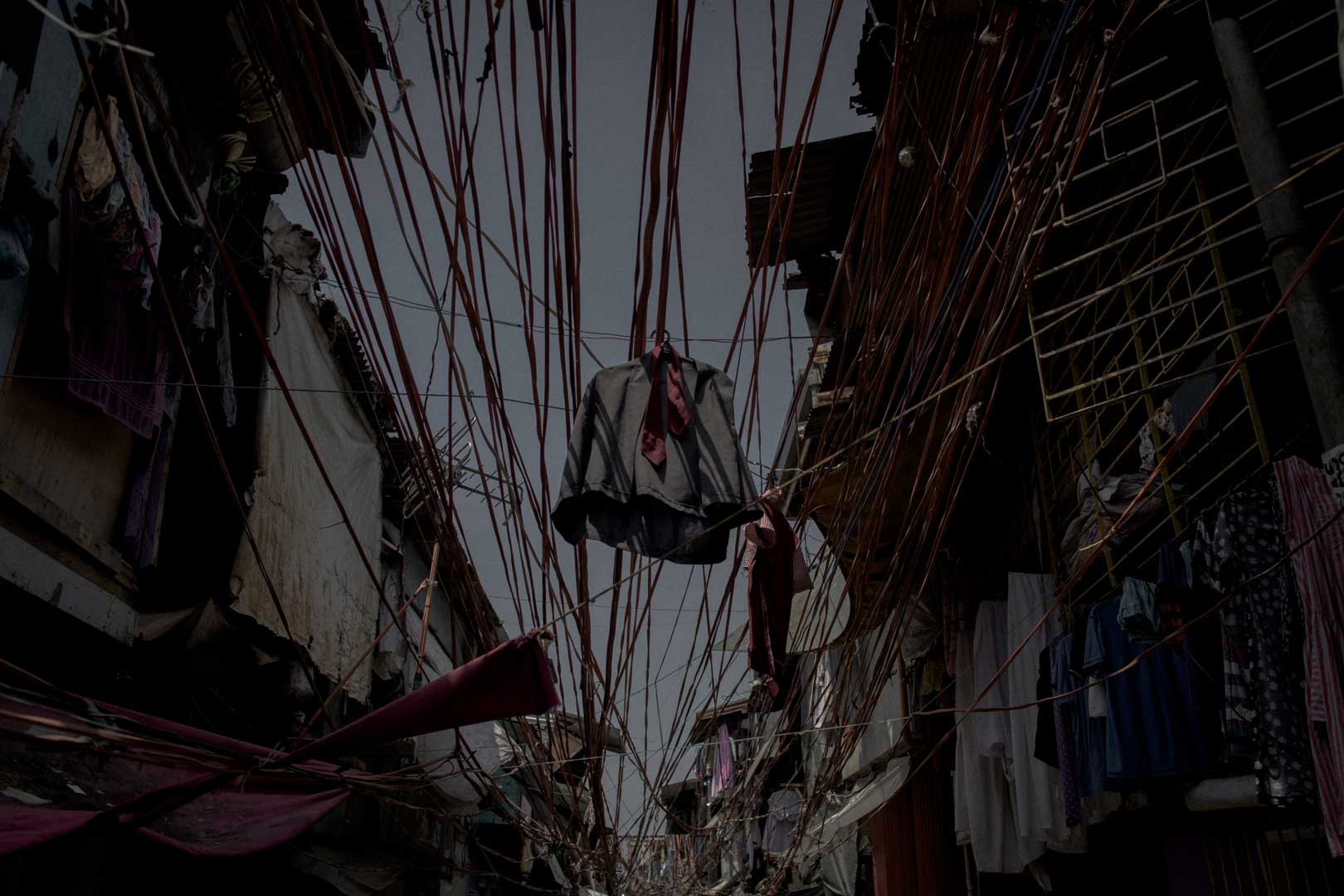

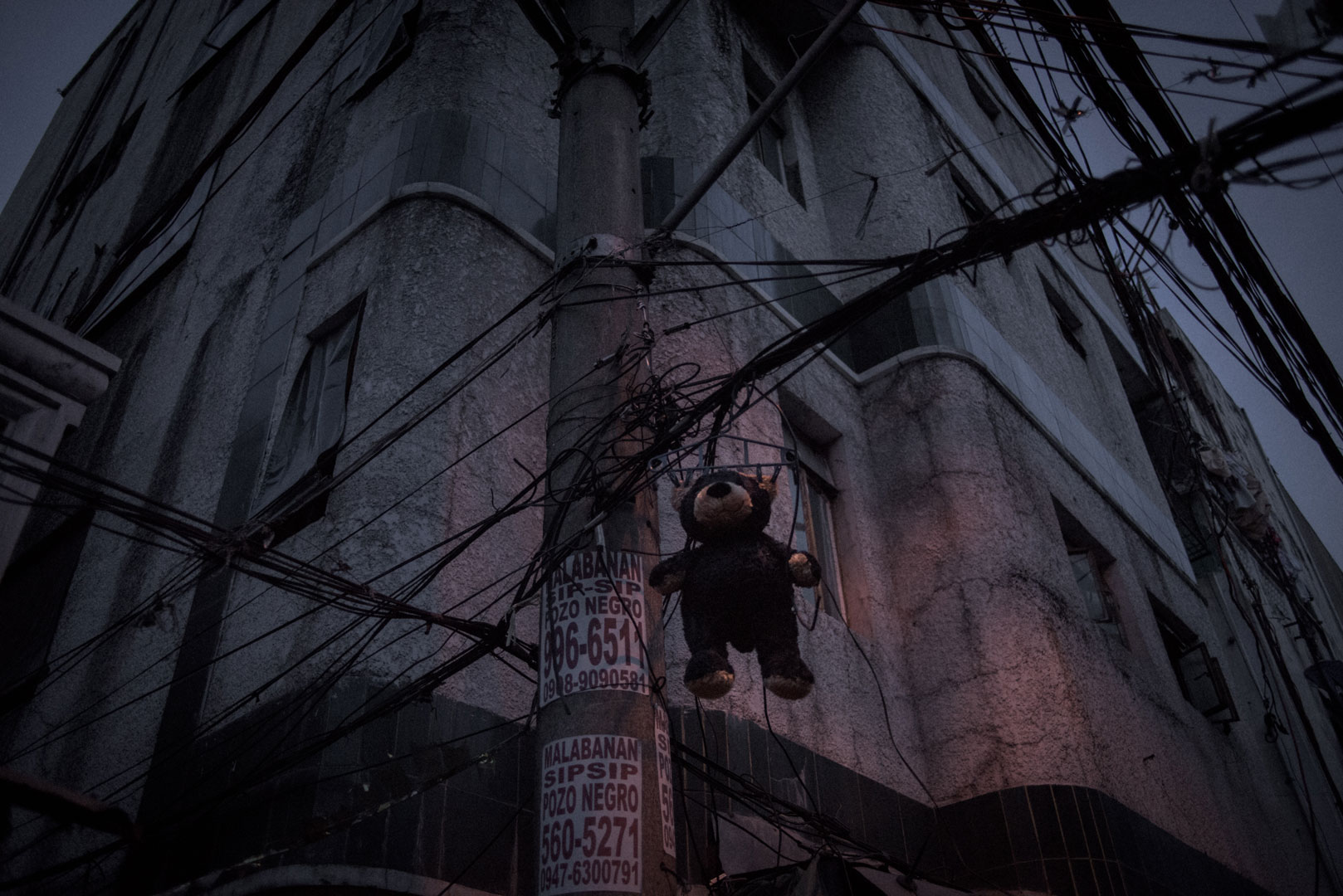

The Cumilangs live in Isla Puting Bato, a sweaty maze of shanties tucked into the curve of the Manila North Harbor. Thick ropes of electrical wiring hang overhead, so low in some places that it is impossible to walk upright. The alleys are makeshift markets – garlic by the bushel, cigarettes by the stick, powdered Oreo-flavored shakes sold beside roasted pig guts. The colors are bright – a purple door here, a yellow awning there, graffiti scrawled big and broad over the few stretches of open wall.

One Friday afternoon, Jimmy, Joshua, and two other young men were sitting on a roadside ledge. The Cumilang shanty was behind them, down a set of stone steps. It was a month before Christmas. Joshua was counting the money he had saved for the holidays.

All of a sudden there were armed men. They were dressed in civilian clothing. Jimmy knew them from their rounds in the area. “It’s the ones who aren’t in uniform who kill here,” he said.

One of them was the man Jimmy knew as Alvarez.

“People would say, ’Stay away from that Alvarez,” said Jimmy. “’Be careful, he’s a killer.’”

That day, Jimmy said, Alvarez had a partner, a younger man whom Alvarez was training. Nobody was certain how they were related. They called him “the other Alvarez.”

The armed men started searching Joshua. They found the money in his sock, took it and pocketed it. They said the 4 young men had been using marijuana – “We weren’t, we really weren’t” – and made them stand with their hands on the tops of their heads. Two of the armed men herded Joshua down the steps to the short alley beside his house.

Joshua’s mother Nenita came charging out of the Cumilang home, straight at the men who had seized her son. “Sir, what are you doing sir, don’t do anything sir, just jail him, please.”

The younger Alvarez walked down the steps and aimed his gun at Joshua. Jimmy said his cousin looked terrified. He was begging, “Ma, Ma, Ma.”

“It never occurred to me to stop them,” Jimmy said. “My mind blanked. I couldn’t talk. My insides were trembling.”

Alvarez aimed a gun at Nenita. She turned to run. The younger Alvarez let loose a shot. Nenita turned. She saw her son on the ground covered in blood. She tried to leap for Joshua. The younger Alvarez turned on her with a gun and chased her all the way to the street where she hid.

Alvarez took aim, said Jimmy, and shot Joshua again.

Neighbors rushed out of their homes after the gunshots. The street was crowded. The men who killed Joshua Cumilang walked over to a store just beside the Cumilang house. Witnesses said the men bought coffee and bottles of water with the money from the dead man.

Jimmy heard Alvarez on the phone. He said Alvarez was calling for backup.

The uniformed cops of the Delpan Police Community Precinct streamed in within minutes.

One of them stopped in front of Alvarez. Alvarez addressed the uniformed man as “sir.”

“Sir, Wawa is gone,” said Alvarez. “He’s dead.”

“Good job,” said the older man. “Good job.” Jimmy said the man raised both fists with the thumbs up.

The men made Jimmy carry Joshua’s corpse into a pedicab. Nenita ran through another alley and jumped in. The two cops who were sitting with Joshua’s corpse glared at her, but said nothing.

The pedicab stopped at an empty stretch of road. Nenita said a cop aimed a gun at her head. They pushed her out just before a boy darted past her to poke his head into the pedicab. One of the cops shifted his gun to the boy.

Nenita said the second cop held the other back.

“Don’t,” he said. “That’s a kid. You kill that one and they’ll slap us with a case.”

Part 3: ‘They rape their mothers’

The trouble with drugs, Police Chief Inspector Rexson Layug told Rappler, is that they leave no man decent.

Layug is the commander of the Delpan Police Community Precinct (Delpan PCP), whose stark white building sits square under the Delpan Bridge. A 22-year veteran, he supervises the sprawling swath of shanties that includes Isla Puting Bato and a chunk of Parola, Tondo.

“When they’re on drugs, sometimes, they’ll even rape their grandmothers,” he explained. “Their grandmothers and their mothers. You can see it in the news. That’s why they rape. Sometimes, they even kill their children, because they think they’re demons.”

Layug was pleased with Project Double Barrel, the President’s national operation against drugs. It was the Duterte administration that increased the number of policemen under Layug’s command and allowed for more aggressive patrols.

Layug is a burly man, with a paunch and a lantern jaw. Since the beginning of the war on drugs, Layug has assigned an hourly beat to Isla Puting Bato, an area he described as one of his more chaotic territories.

It was one of those patrols that killed Joshua Cumilang, at least according to a report filed by the Manila Police District (MPD) Homicide Section on November 18. The spot report – the account of the incident filed by police investigators – described how an anti-criminality patrol walked into Purok 3 of Isla Puting Bato. The patrol “noticed and chanced upon a group of men while examining a transparent plastic sachet in the act of extending over to another male companion.” According to the report, the group scampered away when the policemen arrived.

In the story the police tell, one officer, a certain PO1 Sherwin Mipa, followed the suspect who had the sachet. Joshua ran inside the basement of a small shanty. Mipa shouted for Joshua to stop. Joshua turned, “already armed with a .38 caliber revolver.” He fired twice, and missed.

The report said that Mipa, “sensing that his life was [in] imminent danger [had] no other choice but to fire back,” returned fire twice, “thus hitting the suspect in the abdomen and shoulder.”

The spot report also listed the collected evidence. They included a Smith & Wesson .38 caliber snub-nose revolver without a serial number, a P20 bill, and 5 plastic sachets of what appeared to be methamphetamine hydrochloride – street name shabu, or crystal meth.

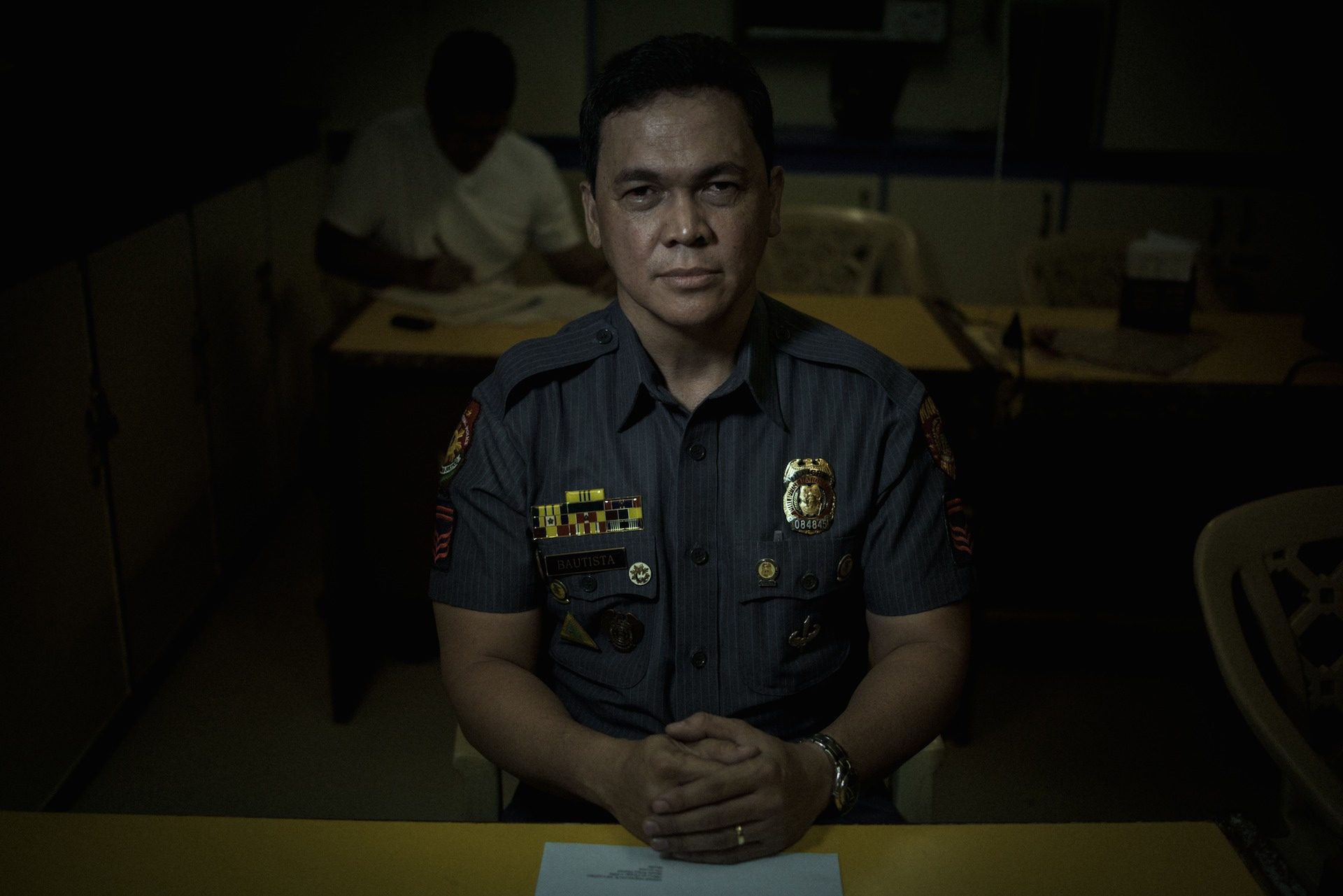

SPO3 Jonathan Bautista, the MPD Homicide investigator assigned to the case, said in an interview with Rappler that he had spoken to Nenita Cumilang. She told him her son did not fight back. She was, however, unwilling to file an affidavit at the MPD. Nenita later told Rappler the family couldn’t file charges: “Will they pay attention to me? We’re little people nobody pays attention to. They salvage the big ones, don’t they? So I did nothing.”

“Inasmuch as I could, I tried to convince her,” Bautista said. “I said, when I was asking her, ’For as long as you have any witnesses, the case will not close. There is still justice.’”

Bautista had written the spot report, but admitted there was some irregularity in the investigation process. Although he said he had spoken to PO1 Mipa, the shooter on record, Bautista said all police officers involved in fatal incidents must each file either individual or joint affidavits to explain their version of events. He said none of the policemen on the scene, even Mipa, chose to submit reports to the Homicide Section. Bautista said he was forced to rely on spot reports written by the investigators of PCP Delpan and PS-2 Moriones.

“To be honest, we’ve hit a blank wall, it’s like we’re in limbo,” he said. “Considering that although there’s this version of the story, the version of the police, I’m waiting for maybe someone with the courage to come out and say something like the allegations [Rappler] told us. Even if we’re cops, we won’t stand back if the guilty need to be punished, definitely. We will file charges against them.”

“Cumilang turned around already armed with a .38 caliber revolver.”

– Homicide Spot Report, 18 November 2016

In his interview with Rappler, Precinct Commander Layug claimed no cop under his watch had ever been injured during the drug war – except for one who slipped and fell in the dark. In fact, he said, Delpan cops had never been shot at or been involved in any armed encounter with any resisting suspect during a patrol or drug operation since the beginning of the drug war.

His claim was a stark contradiction to the MPD’s own police reports and media coverage. At least 11 fatal encounters with police occurred in Delpan alone, including the operation that killed Joshua Cumilang. An entry in the MPD Homicide’s police journal recorded the death of one Marvin Samonte, alleged drug pusher, killed on July 17, 2016. A news report detailed how Samonte was killed by members of the Delpan PCP in an apartment in Pier Dos, Tondo after allegedly resisting arrest.

The police team was led by Precinct Commander Layug.

Asked by Rappler if anyone in his unit had ever been involved in any shootouts with drug suspects during patrols, Layug said no.

“No, no one has ever fought back.”

Part 4: ‘He looked for Mama’

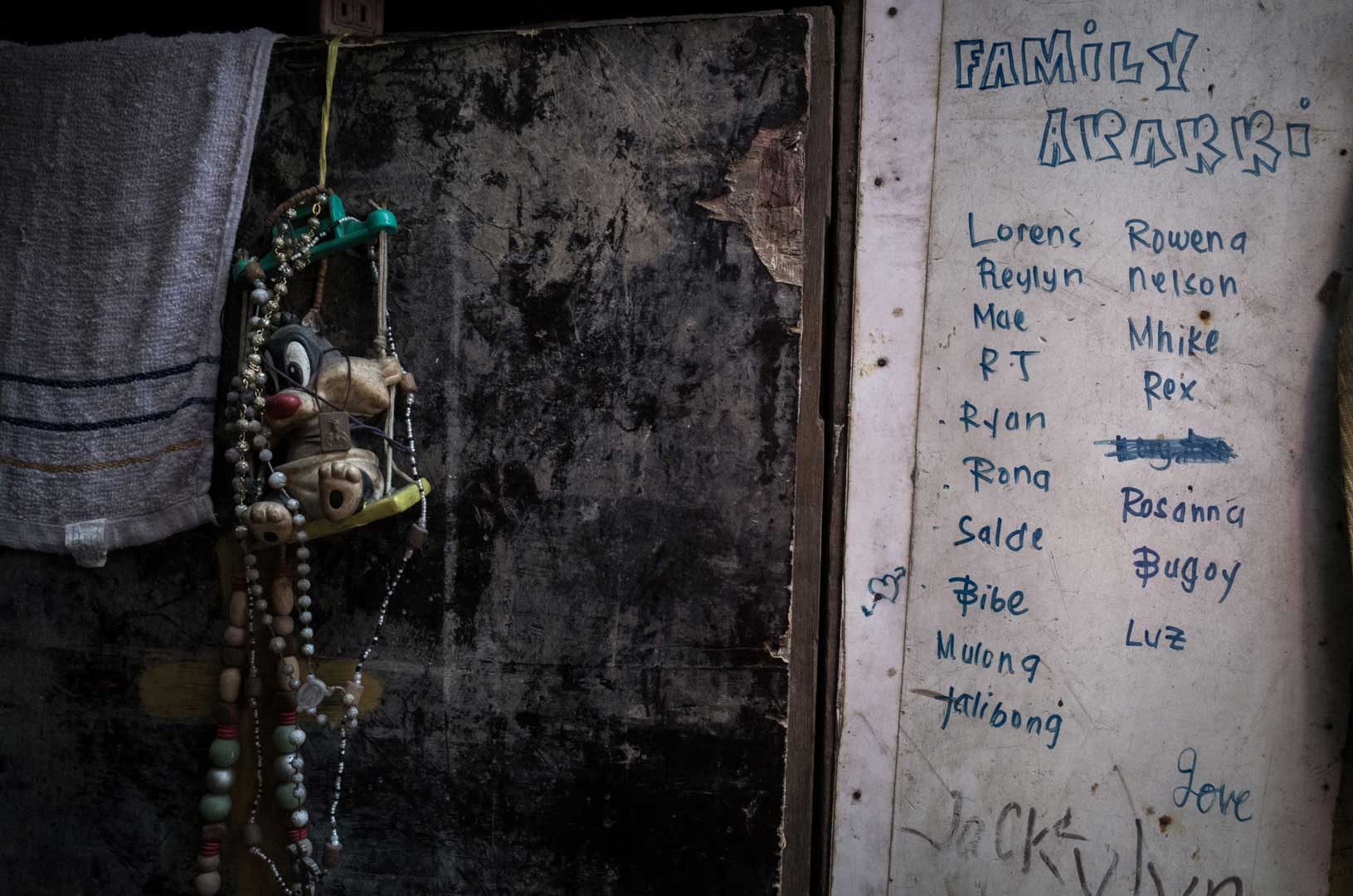

On the day after his son died, Nelson Aparri knelt just inside his front door with a rag and a bucket. He talked while he scrubbed. He said he was sorry. He said he couldn’t even the score. He said maybe God would deal with the killers, because he couldn’t himself. He bent over the floor, a lanky man in his late 50s, slopping water and tears over his son’s blood.

It took a long time to clean.

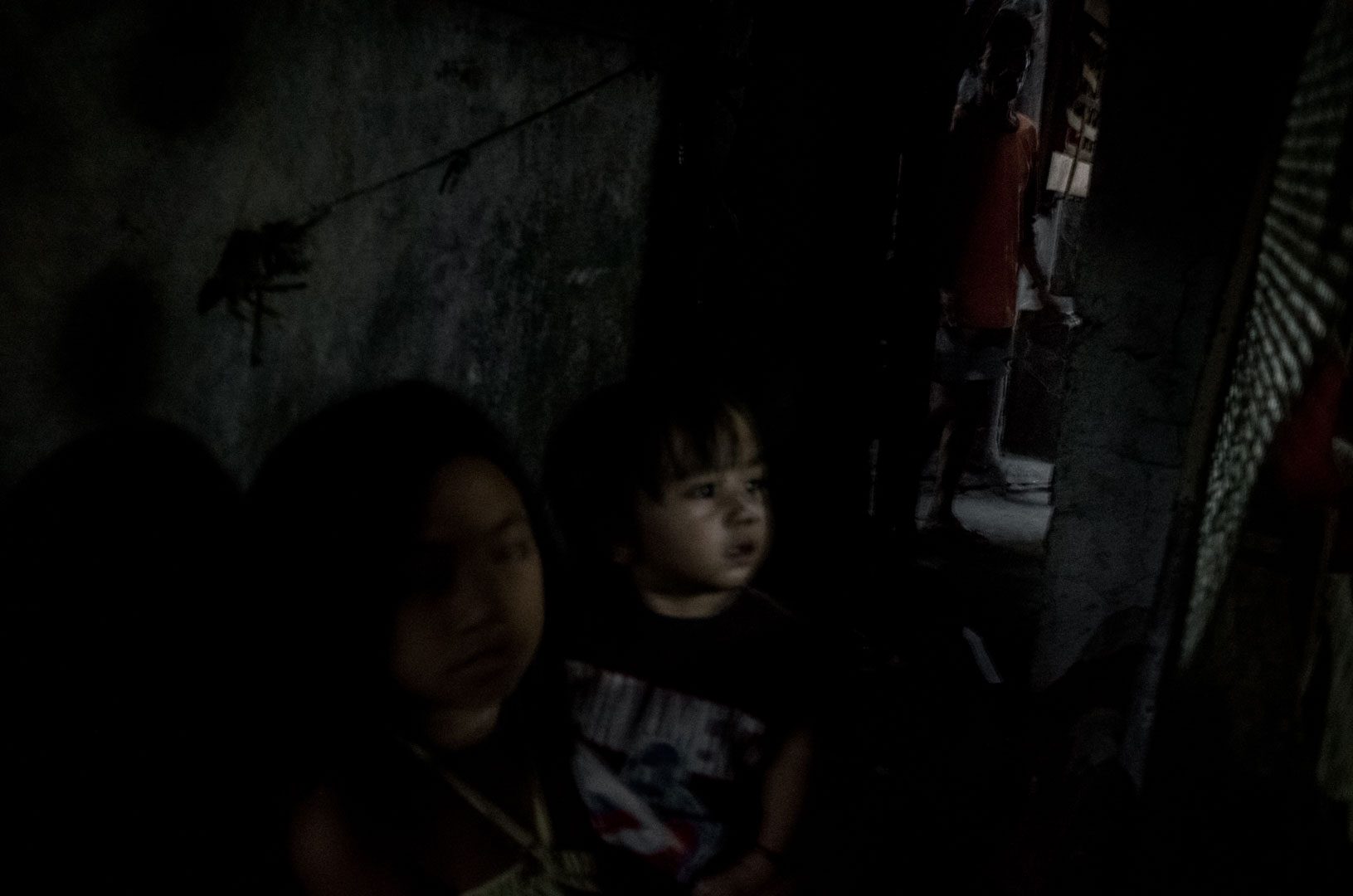

It was Nelson who was closest to Rex. Rex was Papa’s boy. Even his mother Rowena agreed. It was only that night, just before the first shot was fired, that Rex Aparri screamed for his mother.

“When he was about to die,” Rowena said, “he looked for me.”

The house in Isla Puting Bato where 30-year-old Rex Aparri was killed sits along a short, skinny alley, so skinny that it’s possible to step out of one front door and into the door across. On September 13, 2016, at a little past 7 in the evening, word spread across the village that cops were coming. Nelson was afraid the family would be targeted, as Rex occasionally ran drugs. He had heard that every man inside a house during a raid ended up dead. He tried to drag Rex out with him.

Rex was stubborn. Not me, he said. They’re not after me.

Rowena stayed. So did Rex’s girlfriend Lori Ann and their 10-month-old son.

There were 5 armed men in all, none of them in uniform. Rowena was sitting on the front door’s ledge. One of the men shoved her backward. She fell, Rex’s son in her arms.

The man, she said, was the one Isla Puting Bato knew as Alvarez.

Alvarez told her they were looking for Rex. Two of the men stayed outside, shouting at neighbors to keep out of the way, threatening a teenager who had poked his head out of a window. Alvarez and another man climbed up the ladder to the second floor where Rex was tinkering with a radio. The fifth man stayed in the living room. He had Rowena and Lori Ann sit at a corner by the open door. He told them to put their mobile phones and wallets on top of the television. The women sat for half an hour, until the man guarding them walked to the bottom of the ladder with a folded packet in his hand – what Rowena assumed was drugs. He called to the men upstairs.

“Sir, you can have him brought down, sir, we’re killing him. It’s positive.”

Rowena began shouting – “Sir, he has nothing sir, how can it be positive?”

Alverez and a second man brought Rex downstairs. He clung to the banister, weeping. “Arrest me, please don’t kill me, I have a son.”

Rowena pushed the baby at Rex – “So he would have a shield” – then threw her arms around her son. It was a tangle of bodies, everyone pushing and shoving in a space the size of a bathroom. A mirror broke. One of the men hit Rowena with a gun, and kicked her out into the alley. She blacked out.

Lori Ann screamed. One of the armed men shoved her out, snatched the baby by the hair from Rex, then threw the wailing boy out to where Lori Ann knelt in the alley. She caught her son and knelt begging through the open door.

At the second shot she ran, and told Rowena that Alvarez had just shot Rex – straight through the back of the head.

Nelson Aparri, standing in a nearby alley, heard the gunshots. He began to run home. Neighbors grabbed him by the arms.

No, they said, don’t go. They’ll kill you too.

Nelson began to cry.

Outside the house, policemen in uniform barricaded both sides of the alley. Young men, friends of Rex, began picking up rocks. Their mothers dragged them back. One cop standing guard attempted to calm the crowd – “Don’t aim your anger at us,” he told one resident. “We’re just backup, and it’s us who’ll have to take the blame.”

There were two more shots.

It was a while before the family was allowed back inside the house. The two mobile phones and the money in the wallets were missing. Rex was sprawled across the living room floor. His head had fallen near the stairs, his feet near the front door.

Rowena said the bullet holes made the shape of a cross – one shot in the head, one in the gut, and one on each side of the chest.

Part 5: ‘The smoke of gunshots’

The death of Rex Aparri was first recorded as Blotter Entry No. 2265. The spot report prepared by the MPD Homicide Section marked the case a shooting incident.

According to the report, Rex Bustamante Aparri was killed by a policeman during Tokhang operations.

Tokhang, a combination of Visayan words toktok and hangyo – knock and plead – is a central element in President Duterte’s Project Double Barrel. The operation, as explained to the public, involves visits from the police to residents named on a local drug watchlist. Suspected drug users and dealers are invited to surrender themselves at municipal halls or police stations. A form would be made available for signing, indicating the person had voluntarily turned himself in and promised to change.

In the case of Rex Aparri, what was meant to be a courtesy visit went ugly fast. In the pecuilar language of police spot reports – a complicated mix of shifting tenses, street lingo, romantic metaphor, and Old English – patrolling officers from the Delpan PCP claimed they had been conducting Tokhang operations. They knocked on the door. They “spotted the herein suspect thereat.” They identified themselves and approached Rex, who “suddenly drew out his gun and fired shot on the approaching lawmen but he missed his mark.” A member of the police team, “sensing that their lives were in imminent danger,” was “constrained to retaliate.”

“After the smoke of gunshots subsided, the suspect was seen lying lifeless on the floor.”

– Homicide Spot Report, 14 September 2016

Four heat-sealed plastic sachets of suspected shabu were listed as evidence, along with a .38 revolver. The gun reportedly had no serial number.

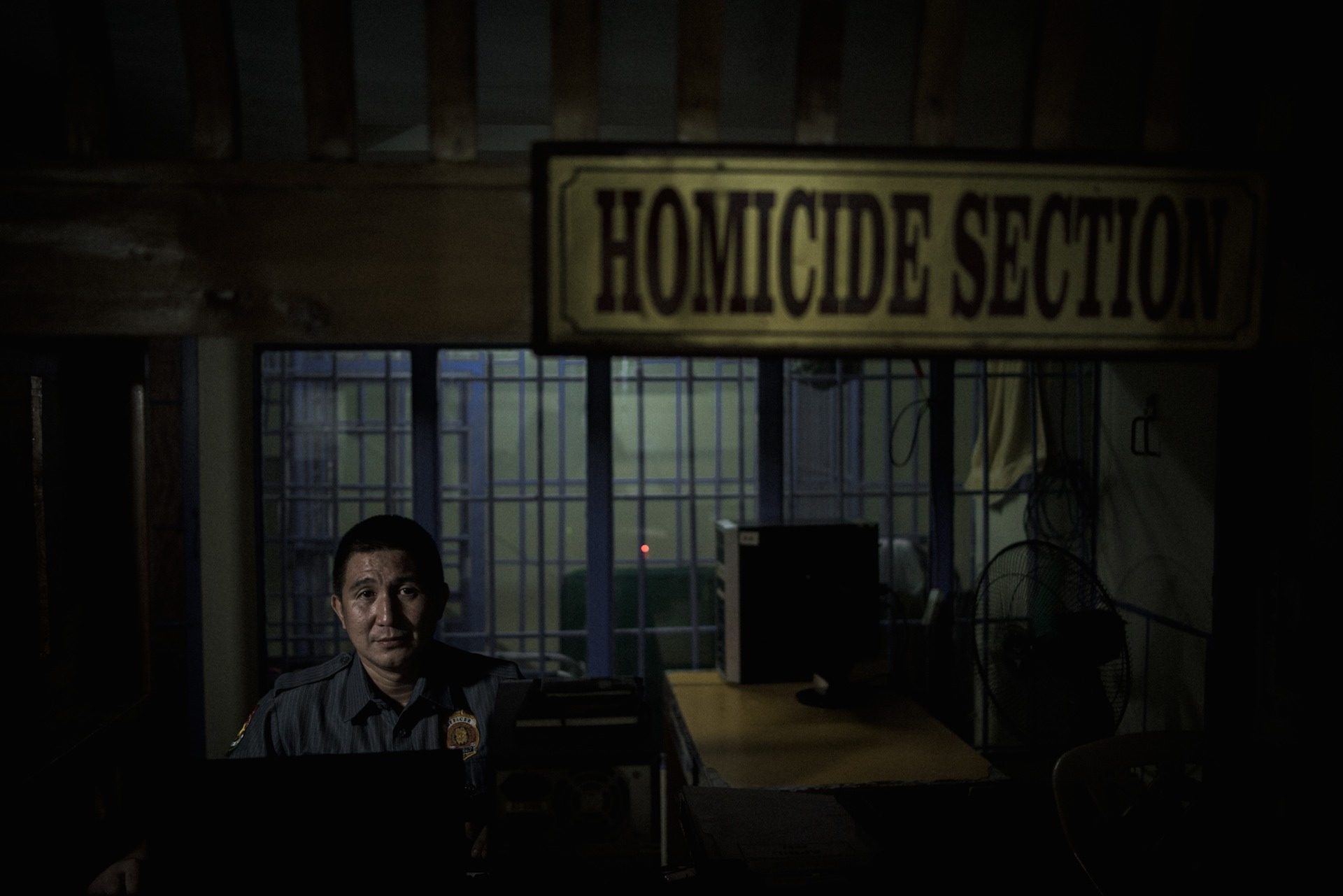

SPO2 Charles John Duran, the case investigator, said he arrived at the crime scene and was surrounded by villagers who told him there was no encounter.

“They were saying he didn’t fight back, he didn’t fight back, but I told them, if there’s a witness, come with us,” Duran said. “They didn’t want to go with us. I told them to come to Homicide if they had time. They didn’t want to.”

Neighbors described to Rappler the minutes after Rex Aparri was killed. In the story they told, Alvarez walked out of the Aparri house and turned into the main alley where the crowd had gathered. Witnesses described Alvarez as a man between 40 and 50. They said he was dark, of average height, with a mole to the right of his nose and a big round belly under the white T-shirts he liked to wear. Although he had been patrolling since the beginning of the drug war, they were unsure of his first name, or if he even remained officially employed by the Philippine National Police.

The witnesses who crowded the alleys said that Alvarez aimed his gun at the sky, and fired one last shot. “If anyone asks who the vigilante of Delpan is,” he announced, “tell them it was Alvarez.”

Duran said the spot report he wrote was largely based on the incident report written by the Delpan PCP. Without witnesses willing to sign affidavits at the MPD, “of course we’ll believe the police because we have regularity in the performance of duty.”

In Duran’s report, the man who took responsibility for Rex Aparri’s death was a rookie police officer named Edmar Latagan. He was accompanied on patrol by 3 other officers of the Delpan PCP, including the team’s leader, PO3 Ronald Alvarez.

Part 6: ‘Like a dead chicken’

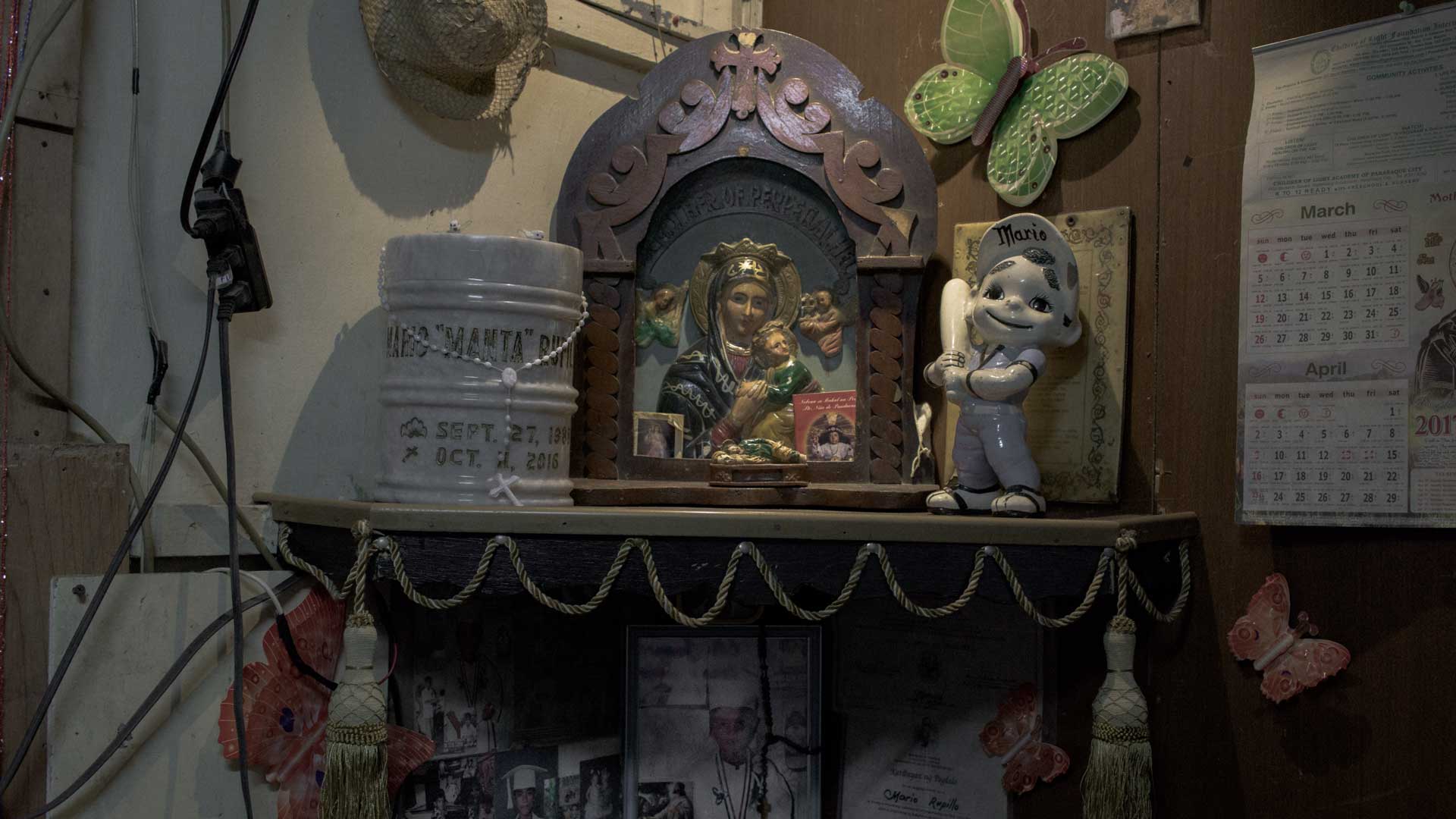

On October 10, a 28-year-old tricycle driver named Mario Rupillo told a friend he was being followed by cops. His body appeared in a hospital morgue hours later. Police said he had fought back at an encounter.

“We accepted what the cops said, because that’s what they say when they have to cover something up,” said Mario’s brother Mark Anthony. “They do that almost all the time anyway.”

Detainees inside the Delpan PCP at the time of Mario’s death told the Rupillo family that Mario had been seen inside the precinct. They added that he was cuffed, and was led inside by the man they knew as Alvarez.

“He’s a cop,” said Mario’s mother Loreta. “He was always dressed as a civilian.”

The same detainees described Mario’s beating to the family. There was an interrogation, they said, Mario whipped by a gun, Mario screaming, Mario refusing to talk.

They said that the last they saw of Mario, he had a sack over his head. He had been dragged out of the precinct by Alvarez just before he was dumped into the back of a waiting tricycle. They said Mario was barely able to walk.

One detainee said a woman, also detained, was in the room while Mario was being tortured.

The local term is palit-ulo, literally an exchange of heads. It is street parlance for a trade – one suspect gives information on another to guarantee his or her own safety. According to the Rupillo family, in the case of the woman arrested before Mario was killed, Mario was the price.

The woman, they said, was released soon after. The family refused to repeat her name. She had bragged to them in public that Alvarez was behind the killing. She said she was under Alvarez’ protection.

The spot report described the police version of events: an anti–criminality patrol spotted Rupillo riding his red SYM motorcycle without a helmet along Gate 14 Delbros of Parola Compound. Mario was flagged down.

“Instead of stopping,” read the report, “[Rupillo] pulled out his handgun and fired shots toward these lawmen but missed.” A rookie officer named Marcelino Pedrozo III had “no choice but to fire back.”

“…instead of stopping, [Rupillo] pulled out his handgun and fired shots.”

– Homicide Spot Report, 11 October 2016

If the police narrative is to be believed, Mario Rupillo was speeding down Parola at a little past 11 pm. He swings out without a helmet, riding his red motorcycle. The cops on patrol flag him down. Mario keeps going as he grabs for his gun. He aims, fires, misses. One cop pulls out his own gun and fires, once, twice, 7 times. The bullets land with precise symmetry on a moving target: two just under the left and right shoulders, 4 on his chest, the last in his mouth.

Mario’s brother Mark Anthony saw the body. He said it looked like his brother had been beaten. Both kneecaps were bruised. Both arms were swollen. Both shoulders appeared to have been broken.

“Have you ever seen a chicken after the bones have been broken, when the wings are just limp?” Mark Anthony asked. “It was that bad, and my brother is even skinnier than me.”

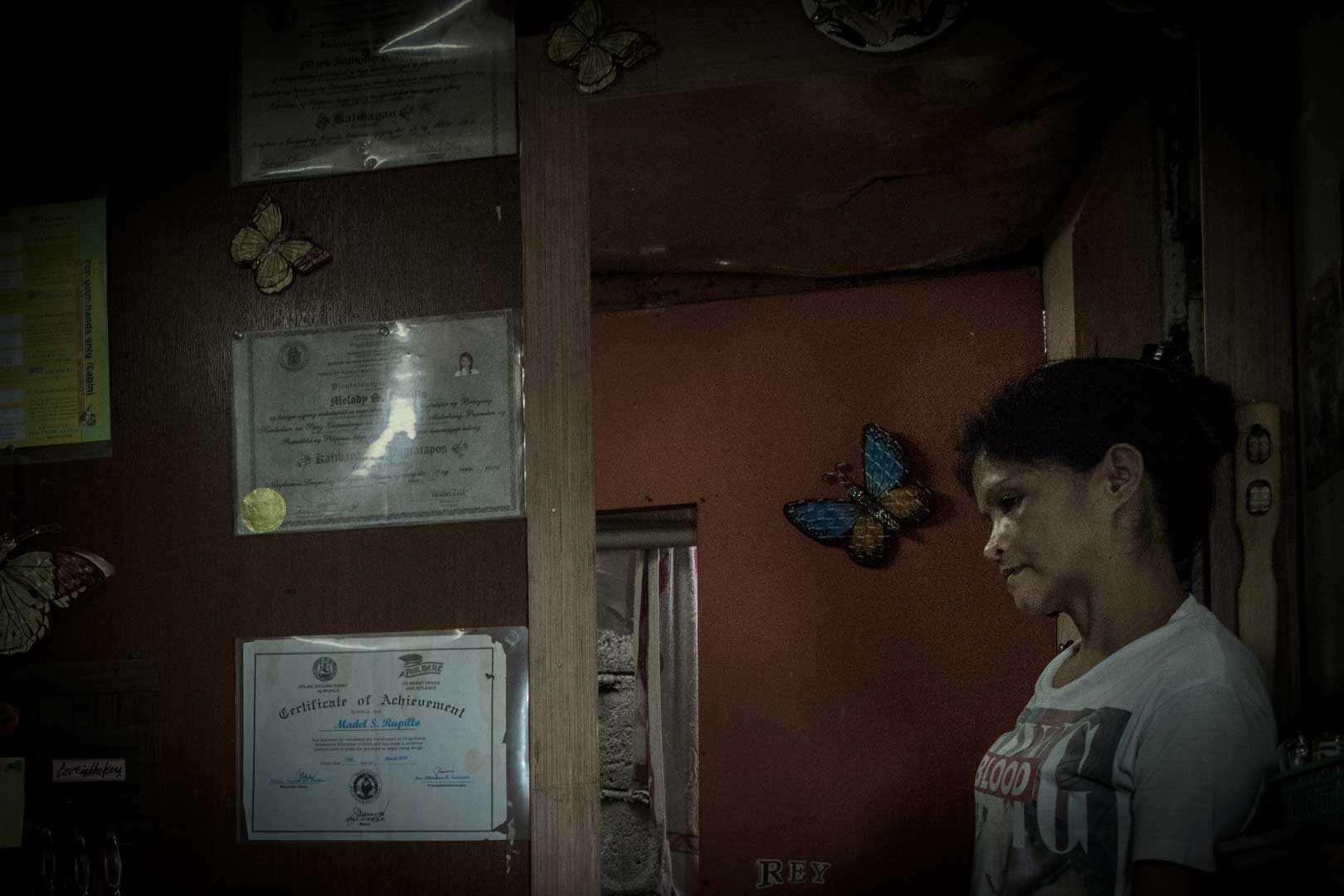

Mark Anthony Rupillo is lanky and soft-spoken, his voice low as he spoke of what he believed was his brother’s murder. Tattoos run the length of his arms, slicking up the side of his neck and down his thighs. His eyes tracked over the afternoon soap opera running silent on the old box television. What was left of Mario Rupillo sat inside a marble vase engraved with his name on an altar overhead.

Mario, said Mark Anthony, was an occasional user before he began running drugs. Someone would come by with money, and Mario would be paid a few pesos after delivery.

Mario’s death certificate, signed by the medico-legal officer of the MPD Crime Laboratory, noted the cause of death as “multiple gunshot wounds to the head, body and upper extremities.” SPO4 Glenzor Vallejo, the MPD Homicide investigator in charge, said he could not recall how many bullets had killed Mario Rupillo. He also said there was nothing unusual about the number of gunshot wounds.

“While he was escaping, he shot at the policemen,” Vallejo said. “So the policemen of course retaliated, and they wouldn’t have thought about whether [Mario] would be hit by a lot of bullets. There was just an exchange of fire.”

Vallejo said he arrived at the crime scene after the body had been rushed to the hospital. He said that his sources were limited to the policemen of the Delpan PCP, and had found no other witness willing to contest the police version of events. He said it was unlikely that Mario could have been beaten while in custody, or that he had been the victim of a trade. He stood by the spot report he wrote, he said, but added the investigation is still ongoing. He said the Rupillo family did not dispute the police version of events when he met them.

The list of recovered evidence included a red SYM Bonus 110 motorcycle with a “For Registration” plate and a .38 caliber pistol without a serial number.

The family said the motorcycle was returned without a scratch. Mark Anthony, who was shown the gun Mario allegedly used, had nothing but contempt for the police. Not only had the gun been planted, he said, but the choice of weapon was ridiculous. The Rupillo brothers may have been too poor to buy arms, but they understood guns.

“We know what sort of gun you can use,” Mark Anthony said, “and what you’re supposed to throw away. That gun looked like you could get tetanus just by touching it.”

Mario, he said, was no idiot.

The last of the evidence was a black bag containing 3 plastic sachets believed to contain shabu, 5 P20 bills, a P50 bill, and a red lighter.

“We knew none of those things belong to my brother,” he said.

Part 7: ‘We killed him’

Joshua Cumilang, Rex Aparri and Mario Rupillo were noted in police reports as suspects killed by policemen from the Delpan PCP in the course of legitimate operations. Each of the 3 allegedly assaulted police with a .38 revolver without a serial number. Each of them reportedly had sachets of shabu on their persons.

The official circumstances linked to the death of 36-year-old Danilo Dacillio are less categorical. In early October, two months before he was killed, Danilo’s aunt Lydia Suarez (not her real name) brought him to the village chief. She had Danilo surrender, then told him to quit using drugs. She gave him enough capital to open a roadside store.

But Danilo still ran drugs, taking a cut from friends who handed him small amounts of cash for drug deliveries. Lydia asked the village chairman to have Danilo arrested and jailed. She said she was afraid Danilo would be killed. The chairman promised it would be done.

On December 2, at around 9 in the evening, Danilo left the North Harbor home he shared with his mother. He was with a friend named Panche. Lydia called the chairman and told him to arrest Danilo. She reminded him to keep Danilo alive. She told the chairman Danilo was on a bicycle. She told him where Danilo was going. She said Danilo was wearing white, and that Panche was in blue. She gave the chairman specifics – “If he doesn’t pass through Kagitingan, he’ll probably go through Pier 4.”

In Lydia’s narration, the chairman said yes. She said it was an hour before he called back.

“We have him,” the chairman said. “But we didn’t find drugs.”

“All right,” said Lydia. “Just jail him.”

“I’ll take care of it.”

One of the neighbors told Lydia that Danilo had been seen at the village hall. Lydia didn’t worry – she was confident he would be safe.

Lydia’s phone rang later that night. The caller introduced himself as Alvarez. Lydia knew him as the cop from Delpan.

“Are you Lydia?”

“Yes, sir,” she answered.

“Is it positive that this nephew of yours uses drugs?”

“Yes sir,” she said. “Sir, please don’t kill him. Jail him, because no one will take care of his mother, and she’s old.”

“I’m not that sort of man,” Alvarez said. Lydia believed the answer was reassurance that Alvarez was not the sort of man who killed. She told him to make Danilo talk about his dealers, then to jail him. She didn’t give it another thought.

Past 11 that evening, she was told someone in a blue shirt had been killed nearby. Then later, another friend called. There was a second body at the bottom of the overpass.

“I wasn’t worried,” she said. “I spoke to the chairman and the chairman said he wouldn’t be killed. So I went to sleep.”

Lydia said she stopped by the Delpan PCP the next morning to see Danilo. She saw Alvarez just as she walked into the precinct.

“Are you Lydia?” he asked.

“Yes sir.”

“I killed your nephew.”

“He’s dead?”

She thought it was a joke. She asked again.

“Right, so he’s dead?”

It wasn’t Alvarez who answered, she said, but one of the cops who stood beside him.

“We killed him. Don’t look for him anymore.”

They told her the body might still be at the morgue.

“I didn’t know what to do,” she said of that time. She left. “I blamed myself, why I even surrendered him. I left, then sat and cried.”

Only a single killing was recorded in the evening of December 2 under the area of responsibility of PS-2 Moriones. Police records do not name Danilo Dacillio or his friend Panche.

“…surprisingly subjects suddenly pulled out their handguns and shot the two policemen.”

– Homicide Detailed Report, undated

According to a detailed report from the MPD Homicide section, at 11:10 pm, elements of the Delpan PCP were conducting a patrol when they saw two unidentified men, one heavily-tattooed, between 35-40, the other between the ages of 25-30. The police “accosted the two male persons for verification and questioning.” The two suddenly pulled out guns and shot the Delpan police.

“Sensing imminent and actual dangers on their lives, both police officers was constraint to fire back.”

Part 8: The ‘demon’ of Delpan

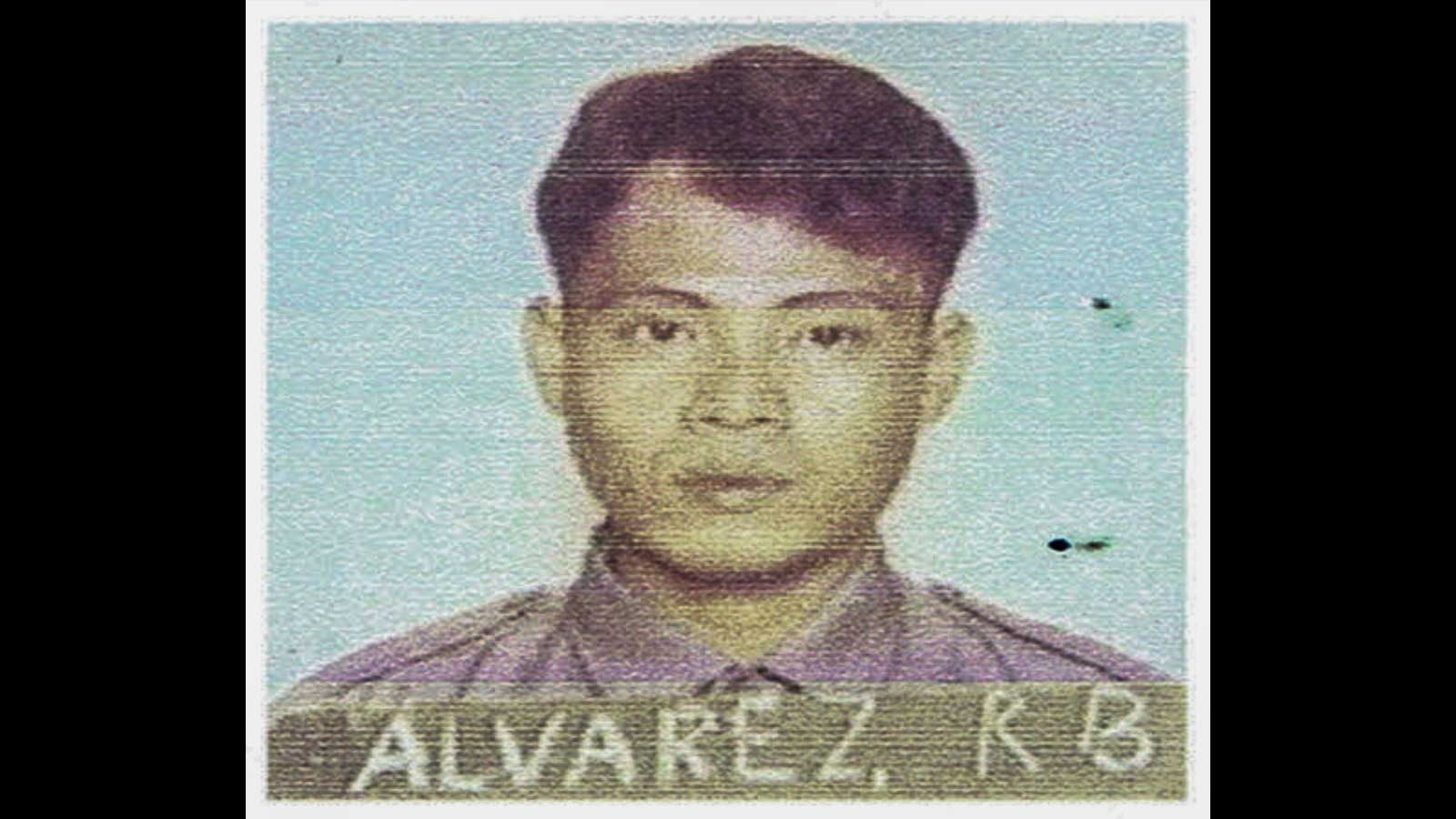

Alvarez has been called many names. The people along Road 10 call him a demon. The people of Isla Puting Bato call him a murderer. Along Parola, he is called “that son of a bitch killer.” Residents who asked to remain anonymous offered his full name: PO3 Ronald Buad Alvarez, beat patrolman of the Delpan PCP.

Rappler has made repeated requests to interview Alvarez. Although his commanders have endorsed the invitations, Alvarez sent word of his refusal, saying that he will not speak upon the advise of his counsel.

Multiple witnesses identified Alvarez by his official photo, made available by the MPD through a Freedom of Information request. The Rupillo family pointed to the picture of Alvarez. They said he was the policeman Mario Rupillo’s friends were referring to when they claimed he had been tortured. Alvarez, they said, was well known.

Nenita Cumilang, Joshua’s mother, identified both the police file photo and a 2016 photograph Rappler acquired of PO3 Ronald Alvarez as one of the men who shot her son.

“That’s Alvarez,” Nenita said.

Joshua’s sister Sara also identified the photo. She herself had her own encounter with Alvarez sometime after her brother’s death.

“I saw my brother’s killer, down near the entrance [of Isla Puting Bato],” she said. “When I passed them, there he was. Alvarez called me.”

She said Alvarez was accompanied by the same men who were with him the day Joshua Cumilang was killed. He demanded she surrender herself as a drug user. He said it was for her own good. She said he carried a surrender form.

Sara said she was terrified, and signed the papers.

Rowena Aparri, who had begged on her knees for the life of her son Rex, pointed to the same photos.

“He’s the one who pushed me,” she said. “He’s the one who killed my son.”

Police Officer 3 Ronald Alvarez, badge number 125658, was officially assigned to the beat patrol of Manila’s Police Station-2 along Moriones on February 10, 2014. The entirety of his recorded tenure with the Philippine National Police has been within the National Capital Region, with stints under the regional office headquarters as well as the southern and northern commands. His personnel record lists 13 citations across his career, including 6 medals of commendation, a medal of merit, and two medals of efficiency for 2015. There are no criminal or administrative marks against him. He has never been suspended. He has never been absent without leave. He has never failed to report to formation. His performance evaluation grade for the last half of 2012 was “very satisfactory,” the second highest rating with a numerical value of 84.

Although Alvarez himself does not maintain social media accounts, his family does. The mole to the right of his nose repeatedly described by crime scene witnesses is prominent in his family’s photos. He blows birthday cakes, dandles grandchildren, sings karaoke, and celebrates holidays. He sits stoic with his eyes fixed on the camera as his wife kisses him on New Year’s Eve. He is there to drive his family to Sofitel Hotel for a day sitting on lounge chairs. He is there at christenings and family gatherings. His name is printed on a T-shirt, along with the rest of his family’s. Online, he seems an ordinary man. There is no mention of his profession, or of his being a cop for close to 20 years. He appears to be Delpan’s secret, the man in the white shirt with the thick gold necklace who introduces himself as a cop and wanders down alleyways allegedly slamming plastic tubs into people’s heads.

Residents claimed he made a habit of walking into village halls to demand protection money from village chiefs. Those within the vicinity of the Delpan PCP also said Alvarez was assigned to the area long before Rodrigo Duterte was inaugurated president.

According to Police Superintendent Arnold Thomas Ibay, commander of Police Station-2 Moriones – under whose supervision the Delpan PCP falls – all police operations, including those with casualties, have been “conducted properly.” PS-2 Moriones has the highest rate of arrests among Manila’s 11 stations, contributing 582 to Manila’s total of 3,850 since July 2016.

Ibay denied allegations of torture and summary execution.

“For me, they did their jobs,” he said. “If they made mistakes, Homicide conducts investigations with regard to the case, and they will have to face it.”

MPD Homicide lists 45 fatalities from police operations under PS-2 Moriones during the 7 months of Project Double Barrel. Rappler studied the spot reports and internal affairs memos of 27 of the cases. (The MPD Homicide Section said the rest of the spot reports were not properly archived.) All of the reports said policemen fought against armed suspects who violently resisted arrest.

At least 13 of the people killed were unidentified in reports, some of them with single-name aliases. The standard for what constitutes a threat to a policeman is unclear.

“That’s their call,” Ibay said. “If they’re in danger where they are, then they have to protect themselves.”

Part 9: ‘They will commit suicide’

Police Chief Superintendent Joel Coronel is categorical that no complaints of human rights violations under Project Double Barrel have reached his office. He said the Internal Affairs Service that investigates every fatal police operations has found no anomalies or illegal actions committed by Manila’s police as of April 2017.

The Director of the Manila Police District is a tall man, clean-cut and gregarious. Although he had been told in an earlier interview of accusations about human rights violations against Alvarez, he was surprised that the allegations were about summary executions. “Not just torture, coercion or what?” he asked.

He said Alvarez remains on duty as a beat patrolman in Delpan, although Coronel added he had ordered a review of cases because of the allegations against Alvarez reported to Rappler.

“I cannot comment on [Alvarez] other than what appears in his record, because I do not know him personally. So based on the record if I look he’s an ideal policeman – I mean not an ideal but he’s what, what should I say, an above-average policeman because he’s very satisfactory, based on his record.”

Told that the allegations also involved other policemen, Coronel said they would have to be investigated too. “If it can be established there’s conspiracy among them, all of them, those who are involved in that operation may be held accountable for murder.”

Rappler requested interviews with 7 of the Delpan PCP policemen listed in the spot reports narrating the encounters that killed Joshua Cumilang, Rex Aparri, and Mario Rupillo. Commander Ibay of PS-2 Moriones relayed their refusal, saying they declined the interviews.

Coronel had a tendency to break into nervous laughter, particularly whenever he was told about the specific complaints against PO3 Ronald Alvarez. He giggled when he was told Alvarez bragged about his kills, and chuckled to himself as he read how Rex Aparri allegedly fought back against policemen. While he said erring cops could be held both criminally and administratively liable for human rights violations, he also presented an alternate scenario.

“It’s possible that the person was already dead when Alvarez shot him,” he said laughing. “I don’t know, maybe that’s possible. The person’s dead, and Alvarez kept shooting him.” He paused, then laughed again. “Maybe that’s what the witnesses saw. No, I’m not one to joke about this, sorry,” he said, then trailed off as he pulled off his glasses.

The chief of the MPD is proud of his district’s performance. Under Duterte and the first rollout of Project Double Barrel, Coronel said the MPD has been able to operate under its own authority, without the clearances once required from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA).

“Anyone,” he said, was allowed to operate – “even beat patrollers.” Reports to PDEA were required only “after the fact.”

PDEA refuted this, telling Rappler there have been no changes in coordination rules.

“I believe we are successful,” Coronel said about Project Double Barrel. The drug war may be ongoing, but the police have the upper hand. Anti-illegal drug operations have gone up. The drug supply has gone down. Crime rates have also gone down, with the exception of homicides. The city has met its required quota of surrenderers, with 46,764 recorded since July 1.

“Not everyone is killed,” he said. “We have more arrests than killed.” The 368 killed since July, he said, are “even less than 10%” of arrests.

The fatalities did not surprise Coronel, as he said drug suspects are expected to fight back.

“That’s really it, they will commit suicide just to hold on to the drugs they have,” he said. “I’m sure they borrowed money to get it. They know their lives are at stake and that drug traffickers will kill them. It’s no different from Mexicans and Colombians.”

Part 10: ‘They wanted it’

On March 29, after the resumption of the drug war, President Rodrigo Duterte said policemen charged with killing drug suspects would be granted absolute pardon if they pled guilty. He referred to the case of 19 policemen charged by the National Bureau of Investigation for the alleged execution of Albuerta Mayor Rolando Espinosa.

“Who will I believe? The witnesses in jail, or my cops? My cops,” declared the President. “They have been charged with murder. I will support them. There is no problem.”

Twenty-one witnesses from multiple cases in a number of locations said PO3 Ronald Alvarez, with a number of other officers, is responsible for at least 5 cases of summary executions later characterized as legitimate police operations. The witnesses come from Isla Puting Bato and Parola, the areas considered by Delpan Precinct Commander Rexson Layug so unruly, they required hourly foot patrols.

Rappler conducted more than 40 interviews in the 3-month course of reporting this story and reviewed the relevant police reports, internal affairs documents, laboratory results, and media accounts to investigate fatalities in police operations within the area of responsibility of PS-2 Moriones.

Some witnesses withdrew their stories out of fear of reprisal. Rappler excluded those from this report. Although some witnesses requested changes in name, Jimmy Walker, Nenita and Sara Jane Cumilang, Rowena and Nelson Aparri, and Mark Anthony and Loreta Rupillo did not. Most of them allowed themselves to be photographed. They were interviewed several times and independently of each other. Other witnesses who asked to remain unnamed validated many of their statements.

The people of Parola and Isla Puting Bato believe they know a killer’s name. Nenita Cumilang remembered the gun he thrust against her mouth. Loreta Rupillo held his picture in her hand, and looked up at the jar holding the ashes of her dead son. Rowena Aparri said his name, and will say it again and again, because it is all she can do for a son she couldn’t protect. Lydia Suarez is afraid for her life, because if Alvarez killed once, he can kill again.

The war was declared on the eve of July 1, 2016. A few hours after he was inaugurated president, Rodrigo Duterte stood at the Delpan Sports Complex and made an announcement.

“Those of you into drugs, I’m done warning after the election. Whatever happens to you, all of you listen, it could be your sibling, it could be your spouse, it could be your friend, your child, I am letting you know, there will be no blaming here. I told you to stop. Now, if anything happens to them, they wanted it. They wanted it.” – Rappler.com

Editor’s note: All quotations have been translated into English.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.