SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Nanoy Rafael, a community organizer, does not know how to ride a bicycle. He wasn’t planning on learning anytime soon.

Until residents of urban poor community Sitio San Roque, Quezon City, were arrested during a violent dispersal Wednesday, April 1. They had assembled to demand food aid.

Because mass transportation, including tricycles, are suspended, Rafael had to walk 45 minutes to one hour from home to San Roque to respond to the community’s call for help. But he quickly realized he couldn’t keep walking for the next days as they try to get the 21 arrested out of jail.

He decided to buy a bicycle from a Facebook seller and used a delivery service. Call it adrenaline rush, but he learned in one afternoon.

“In a span of 4 hours, kailangan kong matuto, kasi sayang sa oras na one hour ka maglalakad,” said Rafael. (I needed to learn, to walk one hour would have been a waste of time.)

Rafael also needed to learn fast what a paralegal does – the case of San Roque would take him out of the community and into the police station, and in a matter of days, the courts. The lawyers would need him.

These are the times in President Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines – paralegals and lawyers alike are forced into the front lines of the pandemic as the government continues its arrests. As of March 31, excluding the San Roque residents, 19,997 have been arrested for violating lockdown rules.

The Supreme Court and the Department of Justice have allowed electronic processes during the lockdown. The case of San Roque was a stress test of that system – with notable gaps that had lawyers stepping out of their homes.

Forced to the front lines

Lawyer Michael de Castro, Mike to friends, has been monitoring reports of people being arrested for violating lockdown rules. Days before President Rodrigo Duterte placed the entire Luzon on lockdown, De Castro had prepared, he had listed down numbers to call, people to contact, an instinctive move just in case he needed to respond.

“We prepared to some extent, but not for this,” De Castro said.

Legal groups have set up channels for those who need legal assistance, but mostly online. Ateneo Human Rights Center (AHRC) executive director Ray Paolo Santiago told Rappler their service is “virtual at the moment.” Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) national president Domingo “Egon” Cayosa said “most legal assistance is being done through the internet.”

“IBP National Center for Legal Aid has Quick Response Teams (QRT) since the start of the lockdown but so far, requests for aid have been for legal advice, not their presence on field,” said Cayosa.

With the arrest of 21 people in San Roque, De Castro knew he had to go out. There was no other way.

“I was raring to go,” he said.

But De Castro only commutes. And Rafael only has a bicycle. Technically, they would be breaking quarantine, and walking, for them, would open them up to more questions from policemen manning the checkpoints.

“Handa na akong maaresto for that (I was ready to be arrested for that),” said De Castro.

A perk of being a community organizer is that Rafael knows many people. So he posts an SOS – he needs a car, a lawyer he knows needs a car, the San Roque residents need their lawyer. Quick.

“Depende na kung sino na ang available that day. Kanina, naubusan na kami at kailangan na naming maghanap sa personal networks namin, ‘yung issue pa dun ay security kasi hindi puwedeng kahit sino, dapat may magva-vouch na safe ang driver na ito,” Rafael said.

(It depends who’s available that day. Earlier, there were no more drivers available so we had to look for one in our personal networks. An issue there is security because it can’t just be anyone, someone has to vouch that we will be safe with this driver.)

With a car ready, De Castro goes.

‘Magic pass’

De Castro and Rafael were linked up through lawyer Kristina Conti of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL).

De Castro and Conti know each other but they lost contact for a couple of years.

On April 1, when the San Roque residents were arrested, De Castro quickly reached out to Conti. They can help, what does she need?

A car, first of all. That’s when she activated her usual network of lawyers and human rights workers, and by 4 pm a car was outside her house.

She prepared to go to Camp Karingal or the Quezon City Police District (QCPD) headquarters.

Based on the latest national guidelines, lawyering is not among the list of essential tasks that are exempted from the lockdown.

“IBP ID ang magic pass sa lahat ng jail,” Conti said. (The IBP ID is a magic pass to all jails.)

In the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), lawyers’ IBP IDs retain their magic.

Conti reached Karingal.

The justice system in a pandemic

The judicial system adjusted to the limitations of the quarantine.

On March 27, the Department of Justice (DOJ) issued an order that would allow an electronic inquest or e-inquest. Inquest proceedings are summary hearings for cases of warrantless arrest. In this proceeding, the inquest prosecutor decides whether or not to uphold the warrantless arrest and charge the person, free him because of an invalid arrest, or free him pending further investigation.

What happened in San Roque was confusing.

According to those arrested, a neighbor told them on March 31 that “there will be a food distribution on 1 April 2020 near Avida Vita Drive corner EDSA, Quezon City,” according to court pleadings.

“Desperate from two weeks of unceasing hunger and an inability to feed their own families, more than five hundred (500) people from Sitio San Roque arrived, fully expecting that food will be distributed around 10:00 AM at Avida Vita Drive corner EDSA,” said the petition for habeas corpus filed Friday, April 3, but is now moot because of the charges.

But there was no food distribution and “instead, some of the residents, mostly children, were randomly given placards by people they did not know or recognize.”

There were reporters there. Microphones were taken out. The residents were asked how they felt. They said that for them, the government was not doing enough.

Then came the police, in full battle gear. The police gave them 10 minutes to disperse.

“10 minutes, 500 na tao? Hindi tinapos ang 10 minutes, hinuli kaagad sila. Nagkaroon ba ng resistance, ng serious disobedience? Paano ka makaka-obey sa isang physically impossible na order?” De Castro said.

(10 minutes? 500 people? They did not wait 10 minutes, they started arresting immediately. So, was there resistance, was there serious disobedience? How can you obey a physically impossible order?)

The lawyers needed the e-inquest. For a minor offense, the police only had 12 hours from the time of their arrest to legally hold the residents in custody. In those 12 hours, according to the rules of criminal procedure, the residents had to be charged in court, otherwise be released.

And Conti knew that. Police knew that. She knew how to play that card.

At 8 pm on Wednesday, the day they were arrested, Conti told the cops: “O, sir, pa’no ‘to, 12 hours lang ‘to, maliit lang ang kaso.” (What are we going to do here, sir, this should just be 12 hours, because the offense is minor.)

“Ah oo ma’am e-inquest naman ‘to (Ah yes Ma’am, anyway this is just e-inquest),” the cop told her.

E-inquest

In the DOJ’s order, the police can e-mail the complaint and other documents for the conduct of an e-inquest. The policemen in Karingal knew that much. But they did not know what to do after that.

“Paano ako? Paano kami mage-enter ng appearance? (How about me? How can I enter my appearance?)” Conti asked.

In an inquest proceeding, the respondents’ lawyer is able to participate. In an e-inquest, the lawyers were at a loss as to how to do that electronically.

De Castro wanted to raise Article 125 of the Revised Penal Code, which says that if law enforcement misses the deadline to bring the arrested to court, then there is a penalty to be imposed on the police.

But it seemed there was no channel in an e-inquest for them to raise that.

There was further delay because the lawyers were told the arrested needed to give their consent to an e-inquest. Apparently, they can choose to avail of the ordinary inquest, to be conducted in person, but only by appointment with the prosecutor.

All prosecutor offices nationwide are physically closed and are reachable via hotlines for urgent matters.

Conti wanted to talk to the prosecutor, but how?

She looked around the station and saw a list of e-mail addresses posted on one of the walls. She saw an email for the Quezon City Office of the Prosecutor, took a photo, and took a chance.

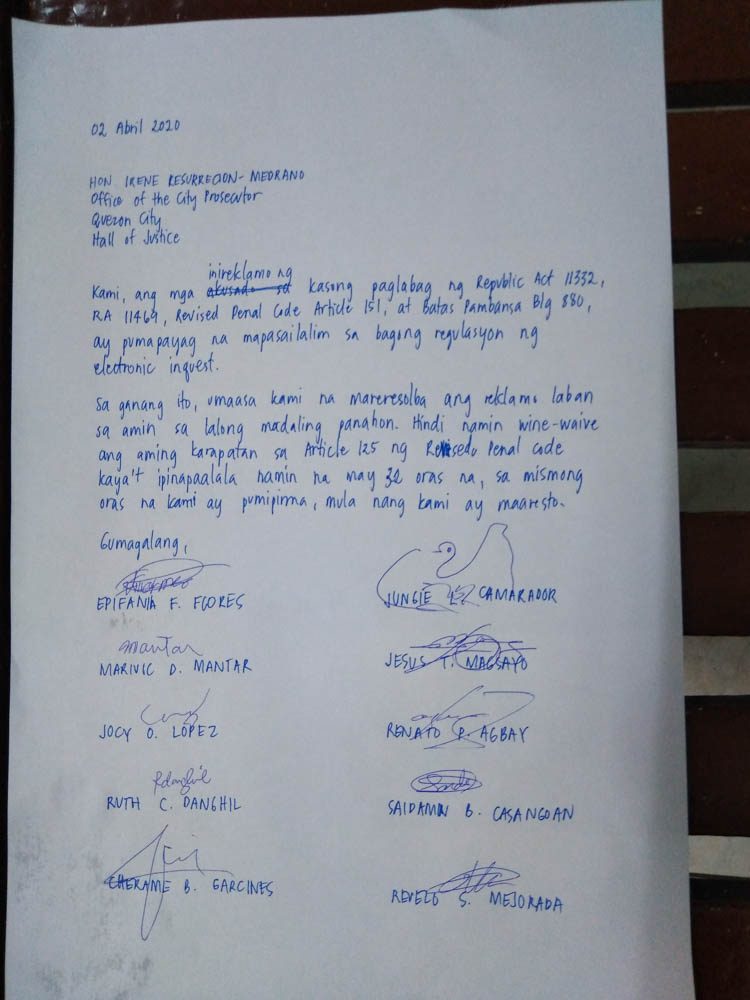

In a handwritten note, Conti got the residents to write to the prosecutor and say they were not waiving their rights under Article 125. At that point, they were already in jail for 32 hours, or 20 hours past the deadline.

Conti also typed out a manifestation, adding that her clients “did not consciously gather together nor conspire to congregate at the place of incident.”

These two documents were e-mailed to the prosecutor evening of Thursday, April 2.

Habeas Corpus

But De Castro wanted the residents released. The 12-hour period had passed.

So he tapped another lawyer from their group Leflegis Legal Services to quickly craft a petition for the writ of habeas corpus (produce the body), an extraordinary remedy to free people from detention.

Jocel Isidro Dilag was unfortunately locked out of Metro Manila. Borders of the National Capital Region had already been strictly sealed.

But no problem, he could do this from home. He invoked Article 125.

“At the height of the grave injustice that the petitioners are forced to bear is that they were only at the area for the promise of much needed food and supplies. No food was given to them, but they were met with unlawful, illegal, and baseless arrest,” said the petition.

“In doing so, the respondents did not only violate their right to liberty, but potentially endangered their right to life, having exposed them to the pandemic, in violation of strict social distancing measures,” the petition added.

The plan was for Dilag to call the Quezon City court and find out how the petition can be e-mailed, and for De Castro to be on standby if personal filing was required.

The Supreme Court has allowed the electronic filing of complaints, information, and even the electronic posting of bail. All courts have also been physically closed.

But on Thursday, April 2, the Office of the Court Administrator (OCA) had not yet issued the final implementing guidelines for e-filing. These came afternoon of Friday, April 3.

Dilag found a hotline for the Quezon City Office of the Clerk of Court (OCC). This was Thursday, but he was told the court is open only on Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays.

Dilag pressed – could he file it within the day, please?

But another problem. The Quezon City Regional Trial Court (RTC) has, for years, been operating on an internal e-system where cases are raffled through that portal and not manually.

“Pero down daw ‘yung raffle system, at kung finile namin ‘yung case, hindi nila alam kung paano mara-raffle. We tried to work out a solution, baka puwede manual raffle? I respect that the OCC would not want to go against the rules,” said Dilag.

(But the raffle system was down, and if we filed the case, they wouldn’t know how to raffle it. We tried to work out a solution, maybe they could raffle manually?)

Dilag pressed on. Hasn’t Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta already said in a March 31 circular that courts can receive e-mail filings?

Many calls were made that day and finally before the day ended, the OCC conceded they would be ready to receive the petition the next day, Friday, April 3, and it would automatically be assigned to the judge on duty.

The OCA would issue Friday an implementing guideline that says raffle of newly-filed cases is suspended and the “judge on duty shall resolve all urgent matters brought before him.”

Personal filing

So it was resolved: the petition for the writ of habeas corpus could be e-mailed and the court would receive it Friday morning.

“But we weren’t taking any chances,” said De Castro. He showed up in court Friday to personally file the petition.

There was another reason that compelled De Castro to again break quarantine.

The petitioners, relatives of the arrested residents, have to personally take an oath before a notary public. Their verifications are required attachments to the petition.

The OCA e-filing guidelines do not say anything about notary.

Asked if the Supreme Court can allow taking of oath via videocall, spokesperson Brian Keith Hosaka told Rappler: “At present 2004 Rules on Notarial Practice is the applicable rule. It does not allow notarization through videocall.”

Conti turned to a reliable contact, a notary public in Quezon City and a human rights lawyer too. It was a challenge to get the verifications, but by 1 pm Friday, they were ready to file.

At 1:45 pm, they were already in court filing.

Charged

But by 3:30 pm, Conti posted on Facebook: “With great anguish we announce that formal charges were filed today against the San Roque 21.”

It turns out that Assistant City Prosecutor Irene Medrano had resolved the inquest Thursday, April 2, finding probable cause to charge the 21 of 5 violations. These were: unlawful assembly (BP 880), non-cooperation in a health emergency (RA 11332), resistance to authority (Article 151 of Revised Penal Code), spreading false information (RA 11469 or the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act), and impeding access to roads (RA 11469).

All in all, the recommended bail was around P15,000 each.

The lawyers knew that with the upcoming filing of charges, their petition for a writ of habeas corpus would be moot.

Once filed in court, the residents can post bail and get out.

But of course filing is a different saga altogether. The QC court had imposed a 2 pm cutoff for transactions. The residents had to stay in jail for the weekend.

The lawyers spent the weekend pooling resources to foot the bill for bail, which summed up to about P370,000. Celebrities – from the megastar’s daughter Frankie Pangilinan to Ria Atayde and Enchong Dee – pledged to help.

Conti set up accounts, and they received varying amounts from P1,000 to P20.50, presumably from students who were donating what they could spare from their allowances.

On duty

By Monday, April 6, Conti woke up hopeful, knowing they had enough money to bail out the 21 arrested.

“As we march into the Quezon City Hall of Justice, we feel and carry along your earnest hope, heartfelt tears, even wrath and indignation,” Conti posted on Facebook.

But again it was a race against time, to make it to the 2 pm cutoff of the court, while completing the requirements of all 21, including IDs that were lost from the arrest to the detention.

Conti even had to argue with the court to accept the residents’ photos printed on bond paper. They needed to be printed on photo paper.

Ayaw tanggapin sa QC Hall of Justice ang required na 2×2 pictures para maiproseso ang piyansa ng mga kinulong dahil hindi raw ito naka-print sa photopaper. pic.twitter.com/bd3E4SKG0u

At that point, De Castro, Conti, and Rafael had been outside for days in Quezon City where there were 500 confirmed coronavirus cases as of Saturday, April 4.

“Nag-resolve na ako sa sarili na sa matter of when na lang (na makuha ko ang virus), feeling ko imposibleng hindi ako mahawa given the state of the community,” said Rafael.

(I have resolved with myself that it’s only a matter of when I will catch the virus, because I feel it is impossible for me not to get infected given the state of the community.)

De Castro said there were more lawyers who helped them in this case, nameless by their own request, and who are continuously monitoring reports to respond to the next one.

“Mali na isasalalay lang natin sa pulitiko, at sa gobyerno mismo ang magpapaandar sa demokrasya natin. Tayo dapat ‘yan na mga tao, aksidente lang na kami. We take it as a duty, as people, simple lang,” said De Castro.

(It’s wrong to just leave it to the politicians, to the government, to run our democracy. It should be us – the people – it just so happens that we lawyers are here. We take it as a duty, as people, it’s that simple.)

Dilag recalls a group of students who consulted him on Section 6(f) of the Bayanihan Law, which punishes the spreading of false information by up to two months in jail and up to P1 million in fines, or both.

More than a dozen people have been subpoenaed by the National Bureau of Investigation over Section 6(f). President Rodrigo Duterte has also told his policemen that if people disrupt order in this quarantine, they can “shoot them dead.”

“Tanong niya, dapat na ba kaming matakot ngayon sa pag-post sa social media? Mali na ba ‘yung ginagawa natin na sumasali tayo sa mga Facebook group? Bawal na ba ‘yun? I think dun nagiging importante ang presence ng lawyer,” Dilag said.

(The student asked: should we be fearful of our social media posts? Is it wrong to join Facebook groups? Is that prohibited now? And I think that’s why a lawyer’s presence is important.)

“Ang presence ng legal volunteers, paralegals and lawyers, help ease the fear,” he added. (The presence of legal volunteers, paralegals and lawyers, help ease the fear.)

Conti has a go-bag. It contains pens and pad paper; pad paper so she can leave a few sheets in jail so the arrested can write his or her account when her recollection is more accurate; whiteboard and a marker to help draw diagrams and illustrate what happened; a clipboard so she can organize all the documents, and her magic pass, always, her IBP ID.

“I know that the judiciary is working electronically now. But the police is not. They’re not working from home. Only when the police work from home can the lawyer work from home,” Conti said.

“This is the most conducive time for abuses. It’s difficult to tell all lawyers to go out there, but those who can, let’s go,” she said. – Rappler.com

TOP PHOTO: Lawyer Michael de Castro and relatives of some of the 21 San Roque residents arrested proceed to the Quezon City Hall of Justice for legal relief. Photo courtesy of Nanoy Rafael

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.