SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Editor’s Note: While a microscopic virus is sweeping the world like the plagues of old, an invisible force – not less powerful – is also shaping the way this pandemic unfolds. In Southeast Asia, the influence of religion during the pandemic is most pervasive in predominantly Catholic Philippines and Muslim majority Indonesia.

In this 3-part series, we bring you to deathbeds in Manila and graveyards in Jakarta, Sunday services in churches and Friday prayers in mosques, to show the role of religion in this pandemic that is often viewed only through scientific lens. After a journey into death and grief in Part 1, we now enter one of the pandemic’s most enduring battlegrounds: religious gatherings.

READ: Part 1 | At the hour of death

READ: Part 3 | Faith in God’s vaccines

The activist Bishop Broderick Pabillo, 66, was stern, unflinching, defiant.

“We should not follow such guidelines that lacked consultations,” Pabillo declared in an interview on church-run Radio Veritas on March 23.

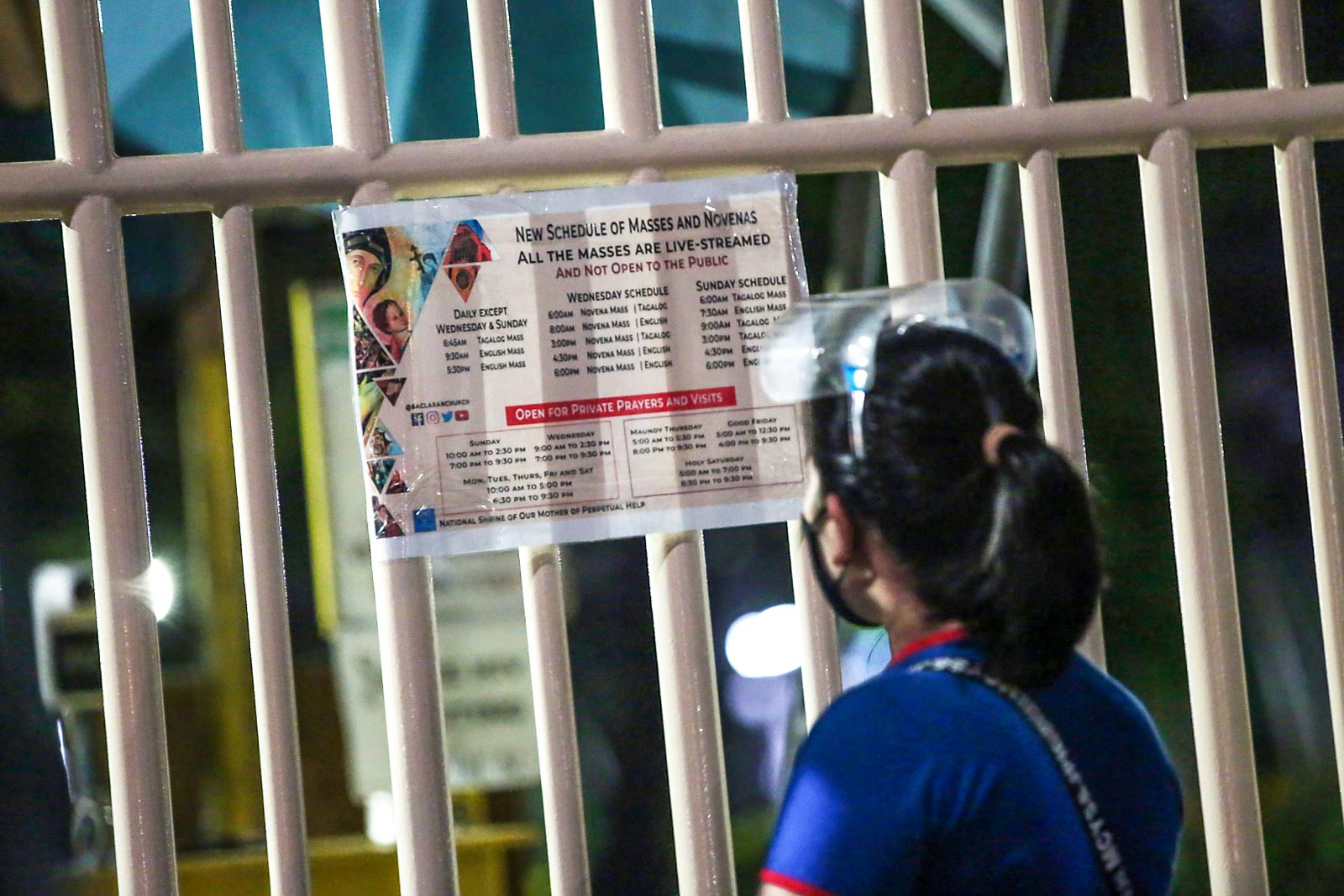

Hours later, he released instructions stating that the Archdiocese of Manila will hold church services at 10% seating capacity despite a government ban on religious gatherings in Metro Manila and 4 nearby provinces for two weeks, including Holy Week. Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque warned that churches can be padlocked, but Pabillo didn’t budge.

Religious services are essential services.

Bishop Broderick Pabillo

Pabillo’s pushback forced the government to reconsider its rules and allow once-a-day religious gatherings from Maundy Thursday to Easter Sunday, April 1 to 4. These revised guidelines, made public on March 26, however, ended up short-lived, after the government a day later placed Metro Manila and the 4 provinces on lockdown due to a COVID-19 surge.

Still, the arguments of Pabillo, a veteran of street protests and a scourge of people in power, continue to echo in church corridors as well as enclaves of policymakers. The averted showdown between church and state depicts one of the most defining debates about religion in the time of COVID-19: Should we ban religious gatherings, and to what extent?

“Religious services are essential services,” Pabillo argued. “Because of their lockdowns, so many people are depressed. They themselves say many people are committing suicide. They themselves say there are many cases of exploitation at home. What we’re trying to cure is the whole person. And in order to have resilience, you have to have the spiritual factor.”

“They should look at the whole person, not only the body,” Pabillo told Rappler.

Super-spreader events?

Religious gatherings around the world, however, have been tagged as COVID-19 “super-spreader” events. In the early days of the pandemic, the virus was said to have spread through Christian churches in Singapore and South Korea, and a Muslim gathering in Malaysia.

In the Philippines, one of those feared to be a “super-spreader” was the annual procession of the Black Nazarene, a 17th-century image of a dark Jesus Christ that is believed to be miraculous. Quiapo Church, which houses the Black Nazarene, canceled the procession this year due to COVID-19, but hundreds of thousands still trooped to the shrine despite warnings.

All I can say is, by the grace of God, in Peñafrancia and Nazareno nothing happened.

Father Nicanor Austriaco

Later analysis by Octa Research, an independent group of Filipino researchers studying the pandemic, found that “there was no spike” in COVID-19 cases due to the Nazareno feast.

“Even in Quiapo, no one said we became a reason for a surge. This means the protocols work, and the people follow,” Pabillo said.

Dominican priest and microbiologist Father Nicanor Austriaco, an Octa Research fellow, also noted that “there was no surge” in COVID-19 cases after the Quiapo gathering and an earlier religious feast, the canceled Peñafrancia festival in Naga City, in September 2020.

“It’s clear that gatherings can be sources of super-spreader events. But in these two cases, neither of them were,” Austriaco said, even as he warned that one cannot make hasty conclusions based on these data.

All he can conclude as a scientist, said Austriaco, was that “nothing happened.”

“We cannot generalize, the pandemic is non-generalizable. So, I cannot say what we will do in the future based on what happened in the past. All I can say is, by the grace of God, in Peñafrancia and Nazareno, nothing happened,” he said.

Ground zero

But fiestas like the Feast of the Black Nazarene aren’t the norm for religious groups. For those debating the safety of religious gatherings, the real battlegrounds – from predominantly Catholic Philippines to majority Muslim Indonesia – are the churches and mosques where believers gather, sing, and pray each week.

In Indonesia, the worship activities of Anwar Abbas, deputy chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), have not returned to normal a year after the pandemic began. Abbas still has to keep his distance during prayers at a mosque near his house in the Ciputat area, South Tangerang in Banten Province, Indonesia.

Abbas knows, on one hand, that praying close to one another in one congregation is God’s command. Maintaining distance from each other, on the other hand, also avoids the possibility of spreading or contracting COVID-19.

Abbas, who is also chairman of a major religious organization in Indonesia, the Muhammadiyah Central Board (Muhammadiyah), remembers a hadith or saying by the Prophet Muhammad. “La dororo wala diroro. We must not injure others and be harmed by others. Therefore we must be careful,” said the 66-year-old man about his reasons for following guidelines to maintain physical distance during prayers.

Another thing he hasn’t done since the pandemic is to shake hands, even if this is customary in Islam. Instead, Muslims greet each other by holding two hands in front of the chest.

According to Dr Corona Rintawan, chair of the Muhammadiyah COVID-19 Command Center (MCCC), one of the big challenges faced in the early days of the pandemic was explaining to the public how to avoid transmission of the virus. “There is a growing rumor that this epidemic is engineered by certain countries to stop the economy, and is part of an effort to keep Muslims away from mosques,” he said.

The head of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) COVID-19 Task Force, Dr Makky Zamzami, said the challenge at the start of the pandemic was how to change people’s behavior.

“The role of religion is very important to prevent the spread of COVID-19. One of them is by disseminating health protocols in sensitive areas such as religious events,” he said.

Faith despite restrictions

One of the religious services affected by the pandemic is the Friday prayer of Muslims.

Some even said I was an infidel.

KH Robikin Emhas

In Islam, the law of the congregational Friday prayer in the mosque is obligatory, equivalent to the 5 required daily prayers in Islam. Those who deliberately skip Friday prayers 3 times in a row can be categorized as having lost their religion, also known as kafir.

KH Robikin Emhas, a religious figure and head of the executive board of the NU, said in March 2020 that he believed Friday prayers could be replaced with prayer at home during the pandemic. That view sparked protests.

According to Robikin, many protested and complained to him directly. “Some even said I was an infidel,” he said. As time went on, however, as infection cases and the death toll continued to rise, people began to accept that view.

NU issued an official statement regarding the law of prayer on March 19. In guidelines issued by NU, Muslims living in the red zone are advised to conduct Friday prayers in their respective homes. The red zone is a category for areas where the virus transmission rate is very high.

The Muhammadiyah also issued a similar recommendation on March 24 and suggested that 5 daily prayers should be held in individual homes and not necessarily in mosques. NU and Muhammadiyah are the two largest mass organizations in Indonesia, with congregations reaching tens of millions.

The policy of maintaining physical distance and avoiding transmission is the main consideration of NU and Muhammadiyah to reopen or not to reopen their educational institutions after the government began implementing the “new normal” last June 2020.

Nahdlatul Ulama houses around 48,000 educational institutions and around 23,000 Islamic boarding schools. Muhammadiyah has more than 10,000 educational institutions, including Islamic boarding schools, throughout Indonesia.

According to Makky, the educational institution that first held face-to-face learning was the pesantren (Islamic schools), last August 2020, after the government introduced the new normal. But the pesantren strictly followed the government’s advice.

Students about to reenter the pesantren are required to take a rapid test. The pesantren also prepared hand washing facilities and introduced the use of face shields. Pesantren caregivers follow government directions.

One of those that opened face-to-face learning earlier was the Nurul Jadid Islamic Boarding School in Paiton, Probolinggo, East Java, which has 8,000 students. “We at the pesantren have responded to COVID-19 since the first announcement by the President,” said Head of Pondok Pesantren Nurul Jadid KH Hamid Wahid on March 21. When deciding to conduct face-to-face teaching and learning activities, all students are required to take a rapid test.

According to Hamid Wahid, religion has provided guidance in dealing with pandemic situations like today, by exerting efforts (endeavor) and surrendering to God (tawakkal). “In religion, if there is a pandemic, people inside will not come out, those on the outside cannot go in. That is what is meant now as a lockdown or social restriction,” he said.

The parents of the santri (students of Islam) complained about the strict procedure at the pesantren. “Now there are fewer complaints and people have started to understand,” he said.

On January 7, the NU Cares COVID-19 Task Force named Nurul Jadid as the best Islamic boarding school in handling COVID-19.

Helping or impeding?

The debates on religious gatherings boils down to the never-ending question: Does religion even have a place in the modern world, during a pandemic that is fought mostly using the tools of science?

Studies abroad have noted the positive role of religion and spirituality in coping with the pandemic. For instance, a research in Brazil published in November 2020 found that the “high use of religious and spiritual beliefs during the pandemic” is “associated with better mental health outcomes.”

Researchers said: “These results highlight the importance of public health measures that ensure the continuity of [religious/spiritual] activities during the pandemic and the training of healthcare professionals to address these issues.”

My faith implies that I will follow measures to prevent COVID-19.

Father Dan Cancino

Yet some critics say that religion can impede efforts to stem the pandemic and its effects.

“The calling for religious leaders to mainly address this issue is downright insulting to mental health professionals in the country, especially when these very religious institutions have created a long-held malicious narrative about mental health,” according to youth group Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan (SPARK) in a statement last August 2020.

In the United States, a study released in September 2020 found that “highly religious participants showed substantially more unreasonable behavior” toward COVID-19 compared to participants with low religiosity.

Still, based on his own experience, Father Dan Cancino believes that one’s faith can influence people to do what is necessary to protect themselves and others. Cancino, who is also a doctor of public health, is a Catholic priest who ministers to victims of COVID-19.

“My faith implies that I will follow measures to prevent COVID-19. I have a responsibility to my neighbor, that is why I will get myself vaccinated so I can help achieve herd immunity. That is my responsibility to others as a person, as a disciple of Jesus, because this is what is taught by God,” Cancino said.

Pabillo – who complained that the government, before his pushback, never consulted the religious sector about quarantine rules – said policymakers always need to consider religion.

This, for Pabillo, entails dialogue. Pabillo said the Philippine national government, unfortunately, had not consulted religious leaders about quarantine measures before he complained about the ban on religious gatherings on March 23.

That the government relented and granted Pabillo’s request means church and state can always find a middle ground – as long as they talk. The bottom line is their common denominator: serving people.

“In our view, a person is a person,” Pabillo explained. “A person needs the emotional, the spiritual, the psychological. And if we will address the needs of the people, we need to address them as persons.” – with reports from Jezreel Ines/Rappler.com

(To be continued. Part 3 | Faith in God’s vaccines)

This story, a collaboration between Rappler and Indonesia’s Tempo Magazine, was published with support from the Sasakawa Peace Foundation.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Wide Shot] Peace be with China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/wideshot-wps-catholic-church.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=311px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] A critique of the CBCP pastoral statement on divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-cbcp-divorce-statement-july-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=285px%2C0px%2C722px%2C720px)

![[The Wide Shot] Was CBCP ‘weak’ in its statement on the divorce bill?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/cbcp-divorce-weak-statement.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=258px%2C0px%2C719px%2C720px)

![[Rappler’s Best] US does propaganda? Of course.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/US-does-propaganda-Of-course-june-17-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=236px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Wide Shot] Meet the ‘muslim’ Jesus](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/wide-shot-catholic-muslim.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.