SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 2 parts

Part 2: What prevents swift COVID-19 vaccine deliveries to Philippines’ provinces?

In the Philippines, vaccines are now available more than at any other point in the COVID-19 pandemic. Every Filipino at least 12 years of age is eligible to receive a shot, while boosters are open to all fully vaccinated adults. In a few days’ time, millions more of children at least five years old will be given access to shots in February.

Yet, nearly a year since doses were made available, the Philippines continues to face a stream of challenges. While some regions like Metro Manila have covered nearly all eligible individuals in their target populations, eight or almost half of the 17 regions in the county are still far from reaching swaths of their residents.

An analysis of the Philippines’ COVID-19 vaccine program by Rappler and public health research firm EpiMetrics highlights the largest bottleneck currently facing the vaccine drive on a national scale: logistical and accessibility issues. We also take a look at how people’s willingness, as well as a lack of equitable supply, can delay widespread coverage across the country.

Where PH stands: 53% fully vaccinated

The government is currently targeting to vaccinate 90% of the 111 million Filipinos in 2022. In 2021, the sheer lack of doses alone would have made this impossible, with constrained supply in the first seven months of the vaccination program.

In November 2021, the number of vaccines delivered to the country were only enough to inoculate 67% of the total population. This changed by the end of the year, when a total of over 210 million doses arrived in the country by December.

To date, supply is no longer a major hurdle. Over 213 million doses have been shipped to the Philippines – an amount large enough to cover 106 million Filipinos if a two-dose vaccine regimen is observed. The chart above shows the availability of shots rising above the level of public acceptance, showing that there are now enough doses to cover all Filipinos willing to get vaccinated.

On a national level, a lack of access to vaccines is what hinders inoculations most in the country nearly a year since the first dose was given in March 2021. Yet, several government officials, including President Rodrigo Duterte, have been quick to place the burden of getting vaccinated solely on individuals.

In early January 2022, the Chief Executive issued nationwide stay-at-home orders for the unvaccinated, ordering local officials to locate people in their communities who had yet to get vaccinated and “arrest” those who defied restrictions on the unvaccinated.

It was a position he defended days later, saying such measures were justified to “protect public good.”

But increasing confidence in vaccines has shown that hesitancy is less a hinder to the country’s vaccination efforts at this point in the pandemic. Instead, there is a large gap between the number of Filipinos willing to get a shot and those who have actually been fully vaccinated, showing that, despite the recent deluge of doses, efforts to get doses quickly into peoples’ arms have fallen short.

While public acceptance of shots has climbed to about 86% among adult Filipinos, tracking by Rappler saw that only 54% of the country’s population aged 12 and above were partially vaccinated against COVID-19, while 53% were fully vaccinated.

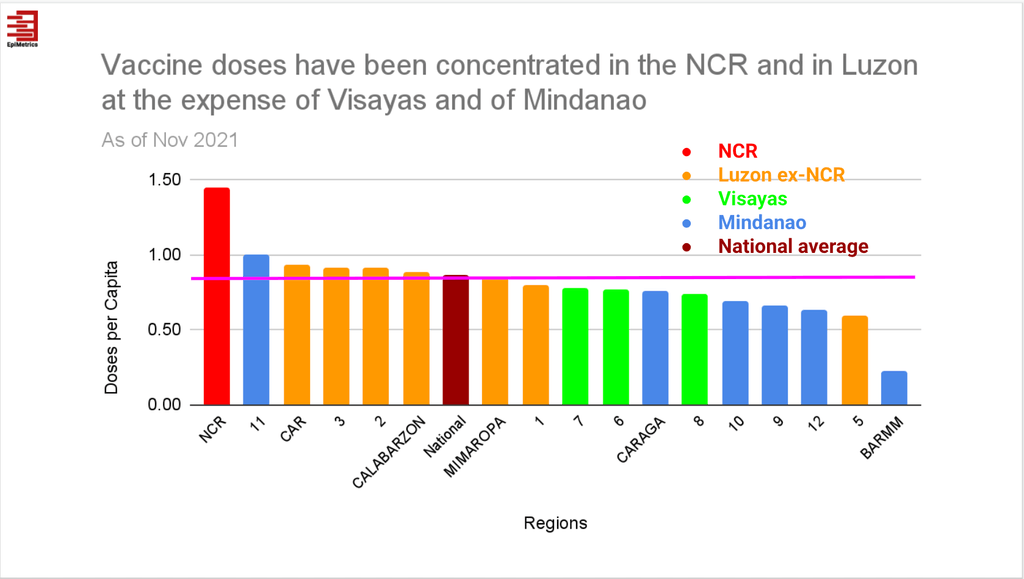

Vaccines concentrated in Luzon

Challenges to accessing shots are partly a result of uneven distribution throughout the country.

Over 10 months since the first vaccine dose was administered locally, Metro Manila is the most vaccinated region in the Philippines, with 109% of its target population fully vaccinated.

This is to be expected since Metro Manila was intentionally prioritized to receive vaccine supplies first, since majority of the country’s cases were located here. But infection numbers aside, Metro Manila was also first in line because of its location as both a hub for international passengers, which often dictated a pattern of cases spreading from the capital region to other areas of the country.

More notably, pandemic response officials placed weight on Metro Manila’s economic contribution to the country in deciding to line up the region to receive most vaccine supplies in the early months of rollout.

As doses trickled in, a similar framework was used to prioritize the distribution of doses to different regions. The national government grouped areas according to “economic risk” and the burden of COVID-19 in communities. Often, these were highly urbanized and densely populated areas like the National Capital Region (NCR) “Plus 8” (surrounding provinces) and “Plus 10” (key cities across the country) grouping.

This framework has partly resulted in continued gaps in vaccination rates across the country. The top three regions receiving the most number of doses – Metro Manila, Davao Region, and the Cordillera Administrative Region – received 2.3 times the number of doses per capita compared to the Soccsksargen, Bicol, and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, which received the least number of doses based on data from the National Vaccine Operations Center, as of November 2021.

“More value was given to more economically productive regions. Because of the inequitable distribution, we see many regions have been left exposed to the virus. Who chooses who gets more and who gets less?” said Dr. John Wong, an epidemiologist and senior technical adviser at EpiMetrics.

Pressure on local governments

Getting doses from central warehouses in Metro Manila down to communities across the country is closely tied to how fast the national government can distribute doses, which in turn depends on how fast local governments can administer shots into peoples’ arms.

As doses started arriving in the country in more reliable flows, the nation’s stockpile increased drastically from scarce to millions of doses on hand in warehouses. In October 2021, vaccine czar Carlito Galvez Jr. said one of the government’s challenges had been “throughput” – or the rate at which doses are administered in a given time. Supplies have grown since then – with about 100 million doses stockpiled as of early January 2022 – yet the obstacle is still one that officials continue to iron out.

With capacities for storage varying across the country, doses are usually handed down from central to regional warehouses, and, where possible, as low as the provincial, city, or municipal levels. How far down the supply chain doses go depends on the preparation and investments undertaken by local officials to prepare for their mass vaccination campaigns.

In cases where vaccines can only be stored as far as the regional or provincial level, local officials work out how to best store and move doses as needed.

To further smoothen out this process, supply chain managers were brought in from the private sector to cover gaps in managing doses. With the national government, a system was created where the performance of local government units (LGUs) were tracked based on how quickly they are able to use up doses on hand. The faster shots are administered, the sooner communities could receive more shots.

By December 2021, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) put this into writing, implementing a memorandum where provincial officials were directed to distribute vaccines to their municipalities and cities within three days from the day supplies were received. In turn, the local government units must ensure shots were administered within 15 to 30 days after receiving them.

The DILG had likewise warned local officials administrative cases could be filed against those who failed to efficiently manage vaccine supplies.

Health systems protected, lives saved

Being among the first to receive doses, wealthier cities and provinces, then, were also the first to fully vaccinate 70% to 100% of their target populations. Alongside supplies from the national government, some cities’ programs were boosted through their own vaccine deals, which added millions of doses to local stockpiles.

Such wider coverage in highly vaccinated areas has led to better health outcomes, as proven in Metro Manila’s experience with the onslaught of the highly transmissible Omicron. While cases had exploded in recent weeks, cases in NCR were now 60% less likely to be hospitalized compared to non-NCR cases, an analysis by EpiMetrics found.

Communities with lower vaccine uptake now face the added pressure of increasing their vaccination rates. Those which received more vaccines earlier were given months-worth of lead time to reach the same targets of vaccinating at least 70% of their populations by May and 90% by June 2022.

On top of this, regions that lag in vaccinations will contend with higher risks that come with skyrocketing cases fueled by Omicron. In areas already seeing fast increasing infections, but still with smaller proportions of their communities having acquired full protection from vaccines, this means that overburdened hospitals and health workers could be left more exposed to the impact of a sharp increase in cases.

In areas that haven’t felt an increase in cases, quicker vaccinations continue to have life-and-death consequences.

“This is the opportune time to rush doses to them and vaccinate them quickly before the surge arrives. They have smaller health care capacity, so they have smaller margins of error,” Wong said.

In recent weeks, cases have started to decline in Metro Manila, while plateauing in the rest of Luzon, offering the prospect of some respite for health workers in these areas. But communities in the Visayas and Mindanao now brace themselves for rough weeks ahead with cases still rising day by day.

Unlike highly urbanized cities and regions that have had far more practice in distributing doses, remote and disadvantaged provinces will face a whole other set of daunting obstacles getting shots into people’s arms. (To be continued.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] US does propaganda? Of course.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/US-does-propaganda-Of-course-june-17-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=236px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.