SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

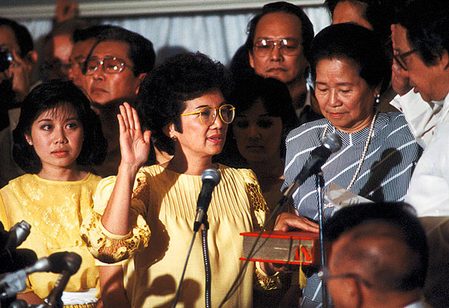

![[OPINION] EDSA was our generation’s mission](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/02/Screen-Shot-2022-02-24-at-6.26.46-PM.png)

February 22, 1986 was a Saturday, and I was in the old newsroom just after lunch hour. The old newsroom was my former newspaper, actually my first job. The owners of the paper were Marcos cronies. Well, truth be told, practically all media during that benighted period were under the thumb of the dictator.

But that Saturday afternoon, I and the rest of a handful of journalists in that newsroom, had no inkling that history was about to unfold. We didn’t know that the despot was about to be kicked out by a mass of Filipinos.

I am Chito de la Vega, a senior editor here at Rappler, but in 1986 I was a greenhorn sportswriter working for a publication owned by a high-ranking minister of the Cabinet of dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos.

The old office was located in Port Area, Manila. That district was likened to London’s Fleet Street because almost all national newspapers had offices there. Even the then little-known Philippine Daily Inquirer, the newest of the “mosquito press,” debuted in that area.

Mosquito press was the sobriquet to the small and pesky independent media. The Inquirer morphed into a daily when Marcos called for a snap election. Its mission was to be a free voice during that period. I distinctly remember that the Inquirer’s address was at the corner of Railroad at 13th streets in Port Area. Why? Because I applied as a sportswriter that year. I got hired April 1986 and worked there till 2017.

Going back to February 22, the boss was in the editor’s chair, where he usually sits on Saturday’s reading through piles of paper. These papers were either reams of foreign wire stories, or early or advanced submissions of reporters.

The bigger boss, his wife, was there too. She was an award-winning writer and also close to the Marcos family, to Imelda in particular.

I overheard them talking. The mister said something like: “There’s something happening in Crame. Si Johnny and some soldiers are there.” Then they got into some serious talk in a lower volume.

The newsroom was now filled with the ringing of black telephones and dinging of the call bells of telex machines.

Reports from foreign news agencies were sent through telex machines. These automated typewriters or teletypewriters made loud clicking, clacking, thumping sounds when churning reports on reams of papers. And for breaking or urgent news, the telex call bell dings several times to alert editors.

When I peeked at the wire report of the Associated Press among the pile, I recall seeing the word mutiny. I was incredulous. After all, the leading dramatis personae in the Crame crisis was Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile. For the man on the street, Enrile belonged to the inner circle of the most loyal to the dictator.

He was among those who applauded inside the Batasan Pambansa when the rubber-stamp national assembly proclaimed Marcos as the winner of the snap election. On the day of that proclamation there was a collective groan among the people and opposition. The buzz was: Marcos and his minions again stole the elections.

So why this sudden about-face by Enrile? Now, at Camp Aguinaldo, he was calling Marcos’ victory a fraud and saying Cory Aquino won the snap elections.

We were still unaware that this was a prelude to one of the most fortuitous events in Philippine history.

That Saturday evening, Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin went on air via the Catholic-owned radio station Radio Veritas to call on the people “to protect our friends” Enrile and General Fidel Ramos, who were holed up in Camps Crame and Aguinaldo.

It was the following morning when I and my high school buddies decided to go to Camp Crame and join the mass of people. I had a brief talk with my mom just before leaving our house. She did not stop me, but I felt her hesitancy. Looking back, my mother was aware of my activism in college and she knew it was a sense of mission that pushed me and my friends to go to EDSA.

A more heated discussion happened when we fetched my neighbor buddy. His parents told him not to go to EDSA because it was dangerous. His argument was perhaps among the reasons many of us in our generation went to EDSA. “Kailangan ko po pumunta doon. Kailangan ko po gawin ito. Paano na lang pag magka-pamilya na ako? Paano kapag tinanong ako ng mga anak ko, ‘Tay nasaan ka nung people power sa Edsa?’ Anong sasabihin ko sa kanila?”

So there we were at EDSA. It is only snatches of what we did that I could recall. I remember it was impassable, we had to walk from Boni-Pioneer to Camp Crame. Every day we were there, people could be seen listening to June Keithley on Radyo Bandido, the “guerilla radio station” we turned to after soldiers smashed the transmitters of Radio Veritas.

People were also lapping up every special issue of mosquito papers Ang Pahayagang Malaya and Inquirer. On radio, Ramos would go on air and read a roll call of names of high-ranking military officers who had defected and crossed over to their side. We also went to the government television station, where a shootout happened between loyalists and mutineers. We saw the body of a man in military fatigues tied to a rope and being lowered from the TV tower. Later we learned that the soldier turned out to be one of the handful of casualties of the people power revolt.

I can’t recall ever going back to the old office during those three days.

We knew that the end was near, when the nationwide simulcast of the oath-taking of Marcos was zapped off the air just as it was about to begin. In today’s jargon, that was “game over.”

Those were momentous days indeed. On the evening of February 25, I bought a gallon of ice cream and celebrated at home with my family and neighbors the departure of the dictator and his family and the demise of his autocratic regime.

Because of the jubilation, I forgot that I’d just lost my job. The old office never reopened.

EDSA was personal. It was a duty. We had to be there. This was our chance to tell the despot that he cannot steal this election. We did not think we were heroes. But there was a flame burning in our chests which pushed us to complete our generation’s mission. We knew we must do this for our children, for the future Filipinos. – Rappler.com

– Rappler.com

This piece first appeared on “Judgement Call,” a weekly newsletter exclusive to Rappler + members that comes straight from the desk of Rappler editors and section heads. Join Rappler+ to access more content like this.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[VIDEO EDITORIAL] Ito na ba ang huling EDSA?](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Xc08fNWM8Hs/hqdefault.jpg)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.