SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Sear, kill, obliterate: On pyroclastic flows and surges](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/04/pyroclastic-flows-april-2-2021-sq.jpg)

The following is the third in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

The most lethal of volcanic hazards that threaten the BNPP are pyroclastic flows. Unlike the volcanic landslides that Cojuangco was referring to which don’t go very far, pyroclastic flows can travel more than a hundred kilometers.

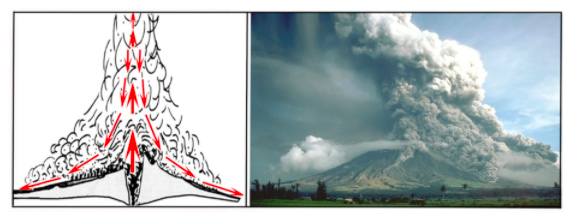

Some pyroclastic flows form out of a single large volcanic belch. Others happen when hot gases mixed with fragmental debris and blobs of lava gush violently high into the atmosphere. Pinatubo in 1991 flung up an eruption column that towered more than 19 kilometers above the ground.

Of course, as the cartoon shows, gravity must slow down the rising hot mixture, stop it, then accelerate it back down. Smashing into the volcano flanks, glowing-hot clouds and denser masses of gas and solid debris rush downslope at great speeds. This photo of Mt. Mayon during its 1984 eruption was taken by Christopher Newhall of the US Geological Survey, an expert on Philippine volcanoes. (Chris later quietly played a heroic, life-saving role during the 1991 Pinatubo eruption.)

In the photo, we only see volcanic clouds rushing downslope. These are the slower, less dense varieties of pyroclastic flows we call pyroclastic surges. They are not very dense, and can override and shroud the terrain. Hidden beneath them are true pyroclastic flows, which are much denser and hug the ground, contained by the valleys down which they flow. Japanese expert Setsuya Nakada says their speeds range from more than 36 kilometers per hour to ten times faster – 360 kph. During the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in the United States, part of the volcano collapsed, generating pyroclastic flows with exceptional speeds of 670 miles per hour – faster than 1,000 kilometers per hour.

No wonder, then, that these mixtures of very hot gases and explosion debris surging great distances down the volcano flanks at hurricane speeds will sear, kill, and obliterate everything in their paths. People seriously planning to activate the BNPP need to understand just how powerful and deadly its impacts can be.

Sadly, nothing better illustrates how pyroclastic flows and surges behave up close than the story of the 1991 Mount Unzen disaster. If you find the following description graphic and upsetting, it is meant to be. Putting an active nuclear power plant in the path of possible pyroclastic flows is very serious business and we better damn well face how they behave in real life.

Mt. Unzen, 1991

Pinatubo’s climactic eruption on June 15, 1991 was so spectacular that it drew world attention and memory away from a disaster that had happened two weeks before at another volcano, one in Japan.

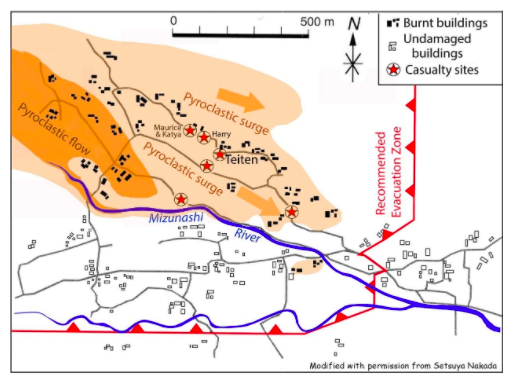

Mt. Unzen had already been active for eight months. On June 3 pyroclastic flows killed 43 people within the area that authorities had declared unsafe and recommended be evacuated.

Notably, the fatalities included three volcanologists: my friends Katia and Maurice Kraft and Harry Glicken. The Krafts were a famous couple, volcano cinematographers whose footage continues to educate the world about volcanic hazards. Harry was a US Geological Survey veteran of the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption. Clearly, even seasoned scientists still have much to learn, and volcanoes can charge deadly costs for the lessons they teach.

The Krafts and Harry were killed on the slope above an outpost called Teiten in the danger area where, emboldened to follow the volcanologists’ example, media people and their drivers had taken cover. Victims and their vehicles were flung 80 meters by the violent blast. Mercifully, they all died instantaneously with their first breaths, because pyroclastic-surge temperatures are typically between 200 and 700°C. Their clothes were burned off and their blood boiled and vaporized in seconds, leaving them charred and carbonized beyond recognition.

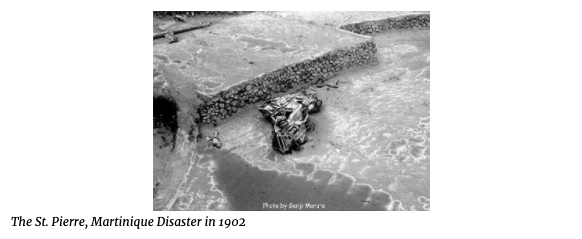

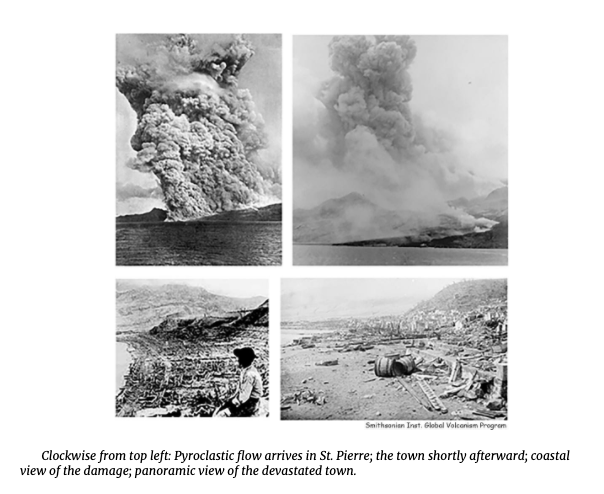

Horrendous as the 1991 Unzen disaster was, it was small compared to the pyroclastic flow that devastated the French colonial town of Saint-Pierre on the Caribbean island of Martinique on May 8, 1902. It provides us with our existing “worst-case” scenario of how bad a disaster confronts northern Bataan, even without an activated BNPP.

Kent Wilcoxson’s excellent book “Chains of Fire” describes in great detail not only how pyroclastic flows devastate and kill, but also how political circumstances can worsen this most lethal of volcanic hazards that threatens BNPP. My book Pinatubo and the Politics of Lahar quotes it at length; I will describe it much more briefly here.

Clear and mounting signs of impending eruption happened for almost a year. The warning signals were so strong the day before it that people wanted to evacuate. But their votes were needed for an election that week, so the authorities cajoled and coerced them into staying.

May 8, Ascension Day, dawned quietly. A huge eruption column was still rising, but the wind was blowing away from the city. Church bells were calling the faithful to mass.

At 7:52 the volcano detonated four times. Then the side of the mountain blew out at about 7:59. We know the timing fairly precisely because the pyroclastic flows that killed all but three of Saint-Pierre’s 28,000 residents stopped the hands of the big town clock at 8:02.

An officer on the Roraima, a ship that was just entering the harbor when the pyroclastic flow arrived, survived to describe what happened:

“The wave of fire was on us and over us like a flash of lightning. It was like a hurricane of fire…. The fire rolled en masse straight down upon St. Pierre and the shipping. The town vanished before our eyes…. Wherever the mass of fire struck the sea, the water boiled and sent up vast columns of steam. The sea was torn into huge whirlpools…. One of these horrible, hot whirlpools swung under the Roraima and pulled her down.… She careened way over…and then the fire hurricane from the volcano smashed her, and she went over on the opposite side. The fire wave swept off the masts and smokestacks as if they were cut by a knife…”

“…The blast of fire from the volcano lasted only a few minutes. It shriveled and set fire to everything it touched. Thousands of casks of rum were stored in St. Pierre, and these were exploded by the terrific heat. The burning rum ran in streams down every street and out into the sea…set fire to the Roraima several times.

“Before the volcano burst, the landings of St. Pierre were covered with people. After the explosion, not one single person was seen…”

Only two people, badly burned, survived. One was a drunk murderer being held in a small jail cell without windows.

He heard and saw nothing. Dug out four days later and pardoned, he spent the rest of his life as a side-show freak in a circus.

At this point in lectures, I pause, sternly eye my students and say: “Let that be a lesson for you.”

BNPP activators beware: Mt. Natib once sent a large pyroclastic flow into Subic Bay. How do we know this? Next foray. – Rappler.com

Previous pieces from Tilting at the Monster of Morong:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Who decides whether Bataan should go nuclear?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/imho-bataan-nuclear-powerplant.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=271px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Nuclear energy should not become major part of Philippine energy system](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/nuclear-energy-january-26-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=205px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.