SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

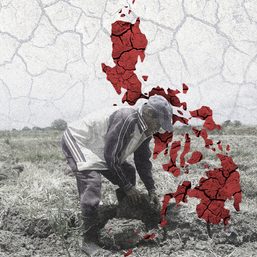

![[Vantage Point] Possible end to water row averts taps drying in Cagayan de Oro, for now](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/vantage-point-cdo-water.jpg)

The Cagayan de Oro Bulk Water Incorporated (COBI) and the Cagayan de Oro Water District (COWD) have agreed to find ways to resolve a money dispute in which the latter has refused to pay the former for services rendered.

COWD has refused to acknowledge that it is indebted to the Manny V. Pangilinan’s bulk water company to the tune of P437 million. According to Engineer Antonio Young, COWD general manager, his company has no legal basis to pay COBI more than the agreed pre-pandemic rates.

COBI earlier sent notices of disconnection to the COWD and warned that it would be forced to discontinue its supply of treated water to the water district unless the outstanding debt is paid.

COWD insists that the amount being billed them by COBI represents an increase in rates implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, despite the water district invoking a force majeure provision in their 2017 contract.

COBI’s lawyer, Roberto Rodrigo, said in a Rappler report that a city hall committee on Wednesday, March 13, that “we did not intend to cause fright among the people. We want to settle this amicably with the water district,” explaining that COBI has been trying to resolve the issue for over a year.

Councilors questioneded a provision in the COWD-COBI contract which allows rate adjustments every three years, Rodrigo said the agreement was reviewed and approved by the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel (OGCC). COWD is a government-owned and controlled corporation (GOCC).

“The mere fact that they cleared the draft of the agreement and the agreement itself implies that there’s nothing disadvantageous,” Rodrigo said. He said the loan applied for by COBI was granted because there were guaranteed automatic increases in the tariff.

COWD inefficiencies

It would be interesting to know how the two parties could resolve the money dispute. The pandemic has little to do with COWD’s financial mess. It only has itself to blame for having an unusually high level of non-revenue water (NRW) in 2021 and 2022. NRW is water that has been produced and is “lost” before it reaches customers. Losses can be real or apparent. High levels of NRW are detrimental to the financial viability of water utilities, as well as to the quality of the water itself.

COWD records show that its NRW reached over 50%, resulting in losses of up to P765.268 million in 2022, an amount enough to have addressed its outstanding payables to COBI. This has in fact been flagged by the Commission on Audit (COA). Had COWD addressed these losses early on, it could have resulted in higher billed volume and effectively more revenues for the water district.

Also, COWD’s receivables from its customers have accumulated to P508.398 million, an indication that it has been remiss in its collection efforts. With this amount, it would have had available funding to implement projects to improve its NRW levels.

Official records also show that the company had P147.24 million available cash and cash equivalents amounting to P227.881 million as of 2022. Again, this could have been used to improve its NRW levels and settle its outstanding debts to COBI.

Why pay for water?

The concept of paying for water services has been a subject of debate and scrutiny for many years. Since water, one of the most essential elements for life, is found in nature, the question often asked is why it should be commodified and monetized.

First and foremost, water that is found in nature is not necessarily pure, and may contain dirt, microbe, and algae. It has to be filtered and disinfected before it can be delivered to homes and businesses. Treating water requires infrastructure, technology, and manpower. Water treatment plants, underground pipes, storage tanks, pumps, and purification processes all require a significant investment in terms of construction, maintenance, and operation.

These costs need to be covered to ensure the provision of clean and safe water to communities. The fees collected from water services often go towards maintaining and upgrading the infrastructure to meet growing demand and ensure the quality and reliability of the water supply.

Moreover, paying for water services encourages responsible usage and conservation. When water is provided free of charge or at a heavily subsidized rate, there is a tendency for individuals and businesses to waste it, putting a strain on and leading to overuse of water resources. By attaching a cost to water usage, consumers are incentivized to use water more efficiently and mindfully, thereby promoting conservation efforts and reducing unnecessary waste.

Water bills also cover the cost of maintaining the facilities that bring potable water, even to low income households that need assistance to have access to safe drinking water. Reliable access to safe water leads to better hygiene and sanitation which results in improved household finances and the economy at a macro level.

Dynamics of water distribution

Ensuring reliable access to clean water requires significant financial resources. Several factors contribute to the friction between water distributors and consumers. Foremost is the disparity in power dynamics. Distributors, whether government agencies or private corporations, wield considerable authority in determining water availability, quality, and pricing. This power asymmetry often leads to grievances among consumers, who feel marginalized and voiceless in decisions that affect them.

Consumers frequently express frustration over opaque billing practices, lack of responsiveness to complaints, and perceived mismanagement of resources. In cases where water scarcity or contamination occurs, trust between distributors and consumers erodes further, exacerbating tensions.

Distributors may prioritize financial sustainability, infrastructure maintenance, or compliance with regulations, whereas consumers prioritize affordability, reliability, and water quality. These competing agendas result in clashes over resource allocation, investment decisions, and rate adjustments.

At the institutional level, regulatory frameworks must evolve to prioritize consumer rights, environmental sustainability, and social equity. Enhanced oversight mechanisms, enforcement of water quality standards, and incentives for responsible water management can incentivize distributors to prioritize the public interest over profit motives.

COBI has obviously taken the high road by initiating dialogues with COWD to resolve the dispute. The move, for now, means water will continue to flow from Cagayan de Oro taps. But it is up to the COWD to do right by its consumers.

Indeed, the contentious relationship between water distributors and consumers reflects deep-seated tensions arising from power imbalances, divergent interests, and institutional shortcomings.

Addressing these challenges requires a holistic approach that would encompass transparent governance, stakeholder engagement, and policy reforms. Without collaboration and trust among stakeholders, access to clean, affordable water will remain a privilege, instead of the fundamental human right that it is for people from all socioeconomic classes to enjoy. – Rappler.com

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

First, the “COWD inefficiencies” in terms of “an unusually high level of non-revenue water (NRW) in 2021 and 2022” and “COWD’s receivables from its customers” are glaring. The COWD management and its policymakers should be held accountable based on the COA report. Secondly, why did the COWD management approve the COWD-COBI contract if it is disadvantageous to COWD? In addition, why did the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel (OGCC) also approve the same contract? Failure to address this issue both in the medium-term and long term-will adversely affect the economic development of Cagayan de Oro City and the welfare of its people.