SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In Indonesia, not all stories are given the same amount of attention in mainstream media; some aren’t even told at all.

A child crying due to hunger, for example, can’t get more than 30 seconds of TV airtime, while a celebrity’s child crying can get two minutes. Human rights violations can be covered up so as not to sacrifice access to a high-ranking military officer.

In that sense, independent production house WatchDoc is a game changer in the industry, producing documentaries about human rights and environmental issues that are often glossed over in traditional media.

WatchDoc Media Mandiri or WatchDoc (from the words “watchdog” and “documentary”) is a media company that was incorporated in 2011. It was founded by two journalists, Dandhy Laksono and Andhy Panca Kurniawan, who were frustrated with the limitations and power play they experienced in traditional broadcast media.

WatchDoc was one of the five recipients of the 2021 Ramon Magsaysay Award (RMA), Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize. They received the award for emerging leadership – the first time this award was given to an organization instead of an individual.

Gaining trust

WatchDoc has a million eyes on them. They distribute their films mostly through two YouTube channels, and their 150 titles average 200,000 views each. Eight of their documentaries have more than a million views.

The internet, however, can be both a blessing and a curse for journalists, who must fight against disinformation on social media platforms and maintain the trust of their audience.

“I think the first thing to maintain to establish your credibility is your independence. This is the most important thing,” Laksono said at a September 9 press conference held over Zoom and organized by the Ramon Magsaysay Foundation.

He added: “Every journalist makes mistakes, inaccuracies sometimes, but if you’re independent, people think that it’s just a common mistake. But if you’re partisan, if you aren’t independent, the mistake could be, you know, interpreted in different ways. We believe that independence is the most powerful gun as media.”

WatchDoc is also open about who their partners are, making sure not to partner with businesses involved in the topics of their documentaries, like mining or palm oil.

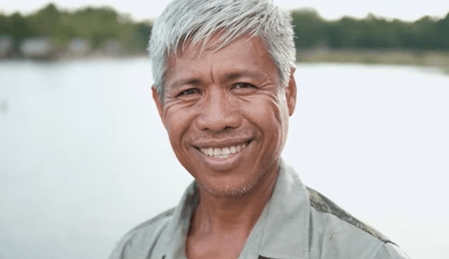

Edy Purwanto, a documentary filmmaker who has been with WatchDoc since 2014, says their audience’s response also lends them credibility.

Whenever they show a film physically in a community, they try to get a discussion going: “What kind of issues were probably relevant in the film?” This creates a ripple effect, prompting action in that community and other communities that can identify with the same problem.

Purwanto spoke to Rappler in a Rappler Talk interview on September 24.

Reaching millions

Purwanto said they began distributing their films through public screenings in 2017, when they showed their documentary The Fake Islands at a fishing village. The Fake Islands is about the Jakarta Bay reclamation project from the standpoint of fishermen and coastal residents.

WatchDoc continues to show their films in communities before publishing them on social media.

These kinds of screenings are key to WatchDoc’s distribution strategy. Where traditional movies are shown at cinemas to earn money at the box office, WatchDoc screens their films anywhere and everywhere to get people talking about the underreported issues they follow so closely.

“This is how we deal with the unreported stuff. We start with the distribution, we start with the platform. There’s no way that, if you have a story like that, you cannot go directly to YouTube, because you need people to gather,” Purwanto said.

You need people talking to each other, you need people making real movement on the field. But if you directly go to YouTube…then people will be disconnected. They will be connected online, but actually they are disconnected in real life.

Edy Purwanto

To reach remote communities with no internet, WatchDoc members have had to travel to share their films. They’ve also shared copies of the files of their documentaries so public screenings could be done through laptops or smartphones. There are times when a village won’t have a theater but would borrow the village generator to show the film to a bigger audience.

Asked about how aspiring documentarists can achieve WatchDoc’s level of success, Laksono reiterated that the spirit of the work they do is sharing unheard stories with the communities that suffer from the issues that the organization tackles.

“In the first place, we did not intend to make a film. I think there’s a big difference. In the first place, we try to help the community, to amplify their voice, help the community to reach a wider audience, to reach out to…public decision makers,” Laksono said.

They don’t intend to make art or win awards, he said, but to inspire the public to act on injustice.

Take action

Laksono described WatchDoc’s documentaries as casual and customized, as each one is shot in a different context.

They could be shooting in an area with no electricity, for example, and so they’d have to rent a power generator to charge their equipment. Or, as Laksono experienced while shooting Expedisi Indonesia Biru (Blue Indonesia Expedition), they could be traveling across the country on only a motorbike to talk to farmers, fisherfolk, and indigenous peoples.

Their brand of filmmaking might have limits when it comes to equipment or the number of people on a team, but it allows for a light, fast, and simple production. It’s filmmaking that anyone can do, and it’s accessible to everyone.

“Just [take] action,” Purwanto advised young journalists who face threats to media freedom in countries like Indonesia and the Philippines.

Indonesia ranks 113 out of 179 countries on the Reporters Without Borders’ 2021 World Press Freedom Index, which describes the country’s media freedom situation as “very difficult.”

“Documentary itself, I think it’s not very tricky or hard to produce. The important thing is our sensitivity to the problem we try to speak up [about] and then how we put the message into what we want to speak up [about], and then just action by recording and editing and then just publishing,” he added.

Technology and social media is liberating to journalists in more ways than one. Other than being able to produce content faster and with less equipment, innovation has also opened the industry to new business models.

“We have a lot of [business] models, independent publishers or small independent media, but very strong, and very decentralized. I think it’s more helpful for democracy, rather than a big, strong, and centered media owned by a media mogul or conglomerate,” Laksono said.

WatchDoc School

WatchDoc has plans to set up a “WatchDoc School,” where they will teach people how to create documentaries. For Purwanto, it’s important that they pass on their craft so they can get more eyes on the ground.

“WatchDoc cannot work alone to criticize and express what will happen in Indonesia, especially. Because we have the limitation in movement – because we are in Jakarta – and because we cannot directly observe what really happens in Papua, in Bali, or in Sumatra,” he told Rappler.

He continued, “So by pushing youths to produce documentary films, we believe that there will be more concern from everybody in Indonesia that can express their expression and their problem and their area through documentaries.” – Rappler.com

The 2021 Ramon Magsaysay Awards will be presented on November 28, 2021.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] Ted Failon, press freedom, and the Supreme Court](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240709-ted-failon-press-freedom-supreme-court.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=296px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.