SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

Several mobile wallets are aiming to capture a slice of the Philippines’ payments pie. And they’re aggressively competing to be adopted by both consumers and merchants.

It’ll take some time before we determine who emerges on top – right now, only a portion of the population is using e-wallets. But here’s how the competition is playing out so far.

The cream of the crop

Among standalone apps, GCash ranks number one on both Google Play and App Store, according to data from analytics firm App Annie. Take note that Android accounts for roughly 83% of mobile operating systems in the Philippines, so you may want to pay more attention to the Google Play column.

Longtime player GCash and rival PayMaya were created by the innovation units of the country’s powerful telco duopoly: Globe Telecom’s Mynt and PLDT/Smart’s Voyager Innovations, respectively.

Coins.ph, founded by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Ron Hose in 2014, is a blockchain-based mobile payments startup that recently sold a majority stake to Indonesia’s ride-hailing behemoth Go-Jek.

PayPal probably needs little introduction. Set up in 1998, the US firm is a pioneer that introduced the world to the idea of sending funds to anyone across the world – online. It’s also a staple secure payment method for e-commerce sites globally.

Another force to contend with is GrabPay, the e-wallet embedded in the app of Grab, Southeast Asia’s leading ride-hailing firm. Grab tops the “Travel” and “Maps & Navigation” categories in the Philippines.

App ranking is a good gauge of an app’s performance. It doesn’t just count downloads, but also factors in things like uninstalls, rating, usage, and more.

However, it doesn’t give you the full picture. Other factors – such as monthly active users, transaction volume/value, competitive differentiation, financial muscle, stickiness, user acquisition costs, revenue, user experience, and so on – matter, and we’ll look into some of these later on.

Same same but different

First, let’s check out the compelling e-wallet models that have popped up worldwide.

In emerging markets with a large unbanked population, a common model is one focused on financial inclusion. Here, an e-wallet is possibly the user’s first experience with a formal financial service, rather than a bank account. The e-wallet can perform basic functions – cash in/out, money transfers, as well as micropayments (e.g. phone credit top-ups).

Then you have the ecosystem play. This e-wallet is part of an app that’s engaged in segments such as transportation, logistics, and shopping. Its users are already kind of digitally savvy, likely banked but do not necessarily qualify for credit cards. The app operator accepts cash as a mode of payment, but its e-wallet offers convenience and greater benefits.

Philippine telcos kicked off their e-wallet services – GCash and Smart Money – in the 2000s with a wider financial inclusion goal. They initially offered SIM-based remittance and micro payments, making use of a vast network of agents – mostly sari-sari stores – to facilitate the transactions. This kind of remittance works this way: a customer hands a store cash, the store sends the amount via mobile phone to another store where the customer’s recipient can claim the money – also in the form of cash.

Years after introducing SIM-based e-money services, the telcos launched app versions to boost use cases and cater to the rapidly growing, digitally savvy base of smartphone owners in the country – whether they’re unbanked or banked.

Coins.ph started out as a cryptocurrency exchange (buying and selling cryptocurrencies) and evolved into a suite of payments services similar to the telco apps.

Meanwhile, GrabPay is part of the Grab ecosystem, which started with ride-hailing and branched out into more services, including courier and food delivery.

Now, all these apps are aiming to transform into a third model: the lifestyle super app.

Many e-wallet providers are eyeing this as an end-state, but few have been able to achieve it. Lifestyle super apps are ecosystems of services that have built an extensive base of active users – unbanked and banked – and have become indispensable in daily life. They’re not just used to pay online, but also in physical stores. Sitting on volumes of customer transaction data, these apps monetize that data by offering adjacent services like micro-loans. The greatest success stories can be found in China, where Tencent’s WeChat and Alibaba-backed Alipay are used by people to pay for almost everything in the country.

An outlier in the local scene perhaps is PayPal, which falls under another model that hinges on payment convenience.

Largely targeting the banked segment, PayPal’s early solution stored and safeguarded bank card details, enabling users to shop on websites via their PayPal accounts without giving away those sensitive details to sellers. For sellers, the US company provided a checkout system for accepting online payments.

In the Philippines, PayPal’s app works the same way, storing card details that users can use to pay other users or businesses with PayPal accounts. It can’t be used for payments in physical shops, but its balance can be transferred to other mobile wallets that are accepted by stores.

What makes them stand out

Though still a ways off, GCash seems to be leading the race to become a lifestyle super app in the Philippines. That’s thanks in part to its progressive and first-mover approach. Thinking that direct peer-to-peer (P2P) transfers are the future, for instance, GCash decided to move away from sari-sari store-facilitated remittance as soon as it launched its app in 2012. The reason was simple: how do you persuade people to go cashless and digital if you don’t eliminate – or at least try to reduce – cash and human intervention in the transactions?

While some may argue the move could mean missing out on the base-of-the-pyramid (BOP) market in rural areas that’s reliant on agents for money transfers, it has allowed GCash to capture more of the urban consumers who are receptive to mobile technology and have higher-value transactions.

Other moves that makes this progressive approach evident:

- GCash forged the first and exclusive QR code payments tie-up (scan-and-pay) with Facebook Messenger

- It’s currently the only one that provides Lazada shoppers the option of paying with just their e-wallet details in a bid to wean people off cards

- Following in the footsteps of its Chinese affiliate Alipay (Alibaba invested in GCash’s parent Mynt in 2017), GCash has plugged in other financial services: credit scoring, loans, savings, and investments

Playing catch-up, PayMaya, which was launched in 2015, has yet to introduce such features. And its SIM-based counterpart Smart Money has maintained the biggest network of agents – 26,000 as of last count, most of which are sari-sari stores. But that’s due to the strong demand that its Smart Padala service has enjoyed from the BOP market, who are mostly located in rural areas with no stable internet connection, and still own feature phones. On the upside, this means a healthy revenue stream for Smart Money and a potential new base of users for PayMaya – if the latter successfully persuades the former’s users to migrate to the app, that is.

Nevertheless, the competition is still in its early days, and GCash and its rival camp are expected to extend well beyond their current focus segments. Moreover, both GCash and PayMaya – by virtue of being owned by the telcos – could have the strongest brand recall and consumer trust among the apps.

Since Tencent, Alibaba’s chief competitor, made an investment in Voyager last year, you could say that the GCash-PayMaya battle is an extension of the war between China’s tech giants.

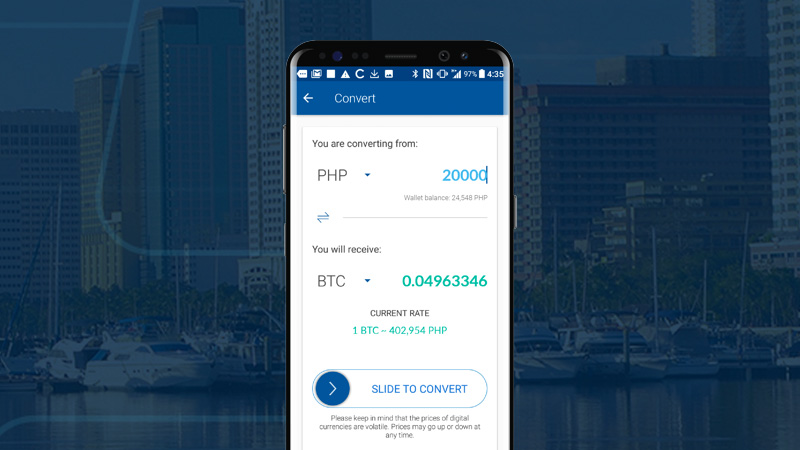

What makes Coins.ph unique, on the other hand, is its underlying blockchain technology. What this means is it can store, transfer cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin and Ethereum), and convert them into pesos, helping it capture a niche. Coins.ph probably got a boost when Bitcoin prices were hitting record-highs a couple of years ago as more people got in on the action. However, the Bitcoin hype started fading as prices slumped.

While cryptocurrencies are considered volatile investments due to wild price fluctuations, blockchain has real utility for cross-border money transfer. Two reasons: it’s quick and cheap.

Settlements using blockchain are instant, versus about an hour through a service like Western Union, or two to three days through banks. That’s because money transferred the traditional way goes through financial intermediaries, which are subject to strict regulation and charge fees. Blockchain keeps track of transactions using a digital ledger where entries cannot be fudged, so it eliminates intermediaries from the picture and lowers the costs (if you want to know more about blockchain, here’s a good resource).

At the moment, Grab’s strength lies in ride-hailing where it has monopoly after beating Uber in Southeast Asia. On-demand transportation is a daily use case that’s hard to beat. The Singapore-based firm’s food delivery and courier features are also gaining a lot of traction among users in the region. While Grab is a frontrunner in launching financial services, including credit scoring and micro-loans, in markets like the Lion City, it’s still in the rollout phase for such services in the Philippines. This means it has to play catch-up with most of the local apps. But Grab’s regional presence also means it has economies of scale – it’s able to share costs over several markets.

For its part, PayPal’s global payments service has become the method of choice among individuals catering to overseas clients.

Next to the US and India, the Philippines’ gig economy is ranked third in the world, with more people opting for online jobs to avoid long commutes and work flexible hours.

Citing data from the Global Freelancer Survey, PayPal claims that its platform is widely used by freelancers in the Philippines (92%), Indonesia (88%), and Singapore (76%). Although domestic clients opt for bank transfers, about 76% of payments from international clients are made via PayPal, the survey notes.

Here’s a comparative look at most of the finance apps’ features:

Here are Grab’s features in the Philippines at the moment:

- Book a ride

- Order food

- Have items delivered by courier

- Buy phone credit

- Send/receive money via QR code

- Link credit and debit cards to pay

Increasing stickiness

In theory, the more services an app has, the stickier it gets since existing users have more reasons to use it (how frictionless and efficient the services are is another story).

Developing new services is also a way to add users and reduce the risks posed by regulatory changes in one sector – for example, transportation. This suggests improved long-term viability.

In the same way, having a vast network of merchants who accept this mode of payment is critical to accelerate usage.

The ease of cashing in is important, otherwise there’s really no incentive for people to fund their e-wallets.

Here are ways to add funds to the different e-wallets:

The ability to convert e-wallet balances into cash or return them to bank accounts is also just as crucial in driving adoption, especially if the market has yet to overcome the trust barrier. Without this ability, it’s like having unused miles stuck with an airline company.

GCash and PayMaya allow users to withdraw cash via ATMs using their linked prepaid cards. These ATM withdrawals, however, come with the usual bank charge. Speeding ahead of other players, GCash now lets users transfer their balances to more than 30 banks in the country for free.

Although PayPal allows transfers to banks, the minimum amount required without incurring fees tends to be relatively high for the general population. In the Philippines, the transfer will not incur charges if the amount is P7,000 (US$138) and above. On top of that, banks impose fees which further reduce the amount to be received by the user.

Below are the different cash-out options offered by the apps:

Apart from drivers’ takings, Grab does not allow users to change GrabPay credits into cash or transfer them into bank accounts. This means Grab will have to contend with providers that offer cash redemption.

Attracting merchants

E-wallets are impractical for people without stores that take them, and no merchant will accept e-wallets if their customers don’t use them. Players have to find a way to build both sides of the marketplace. If an app collects a critical mass of users and merchants, it becomes harder for a competitor to lure them away.

Merchants would find it tough to ignore Grab and GCash’s user base. Grabbers come from across Southeast Asia, where the firm controls the ride-hailing sector and is increasingly encroaching into the travel space through its partnerships (Booking.com is an investor in Grab, for example). Hence, Grab’s local arm is poised to capture tourists visiting the Philippines from neighboring countries.

For its part, GCash has integrated with affiliate Alipay to allow the latter’s users – mostly Chinese nationals – to make purchases from merchants that accept GCash. It’s uncertain whether PayMaya has done the same with its ally WeChat.

In the Philippines, where most payments still happen offline, offering physical stores a mobile payment system that doesn’t require huge capital expenditure is a sound step toward sweeping adoption.

QR code tech is way cheaper than near-field communication (NFC) and the traditional point-of-sale (POS) terminals or cash registers.

Except for PayPal, all local apps have QR code capabilities.

Though Grab’s QR can’t be used in stores yet, the company has struck a partnership with retail titan SM to offer it in malls soon.

Another key selling point is the fact that apps charge merchants lower fees (% of transaction value) for payments compared to credit cards.

Heavy ammunition

With an extensive user and merchant base comes significant revenue potential.

Most apps charge users minimal transaction fees for things bought or paid for on their platforms to fuel adoption.

Even without those fees, there’s potential to earn from users’ balances. In China, Alipay and WeChat Pay hold billions of dollars in funds that accumulate in their apps when users do not immediately use the funds or transfer them to a bank or investment account. The firms invest those funds to generate returns.

However, the companies are said to be losing that revenue after the Chinese government required that all e-wallet funds be deposited in non-interest bearing accounts with the central bank, rather than private institutions.

More than the user fees, players earn from taking a cut of merchant sales – online and offline.

Ultimately, the lifestyle apps serve as e-commerce platforms where third-party merchants and the apps themselves or their parent companies sell their products and services. In this case, payments essentially act as the backbone that allows the transactions to happen. For instance, Globe and Smart are using GCash and PayMaya to sell phone credit top-ups. Coins.ph is offering its crypto exchange and trading services – akin to how a foreign currency exchange service and stock exchange work.

Here’s how many e-wallet accounts there are in the Philippines, as per government data:

And here are the companies’ own user stats:

The picture looks rosy if we go by the players’ numbers. However, it’s uncertain how much of their user acquisition is organic.

App companies spend not just on ads but also marketing promos – cashbacks and price discounts, among other things – to hook price-sensitive Filipinos and foster frequent use.

That’s not to say those subsidies are at all bad. For new technologies, subsidies are a potent – perhaps necessary – tool to acquire users and increase adoption. However, they’re costly to maintain, so winning the payments war will require deep pockets. The road to making money will be long and hard, but there are enormous rewards for becoming the dominant player. The question then becomes: who will last in the game?

All the key players in the market right now have heavy war chests and high-profile investors in their rosters.

The risk with cashbacks and discounts is that they may not necessarily inspire loyalty to a particular brand. In a situation where two players offer exactly the same services, people tend to gravitate towards the one that gives out more promos.

So organic approaches like growing your merchant base and differentiating your product to entice users, as well as robust loyalty programs to keep users engaged are vital.

Grab has a rewards program that lets users gain points as they use the app and progress up the tiers. The higher their tier is, the more rewards they can access. In Singapore, Grab has begun to offer subscription plans wherein users pay a fee upfront to avail of bundled discount vouchers across its services. The plans lock in customers for a longer period: the vouchers are already paid for so people are inclined to use them. What’s even more interesting is that the subscriptions are linked to the rewards program. Rides booked under the subscriptions earn reward points.

On GCash, credit scoring and micro-loans will only be unlocked after a certain level of usage. The app, which currently has the most number of QR merchants, also introduced a program where users get vouchers after a purchase, to keep them coming back.

To better gauge how an app is performing, one can look at active users and transaction volume/value. Unfortunately, the local apps are keeping those numbers under wraps. GCash claims that its active user base has grown 4x from 2017 to 2018.

We reached out to the other players for stats and other info, but have yet to receive a response.

What consumers are saying

Overall, companies will have to compete in terms of the quality of their products and services, including the crucial user experience.

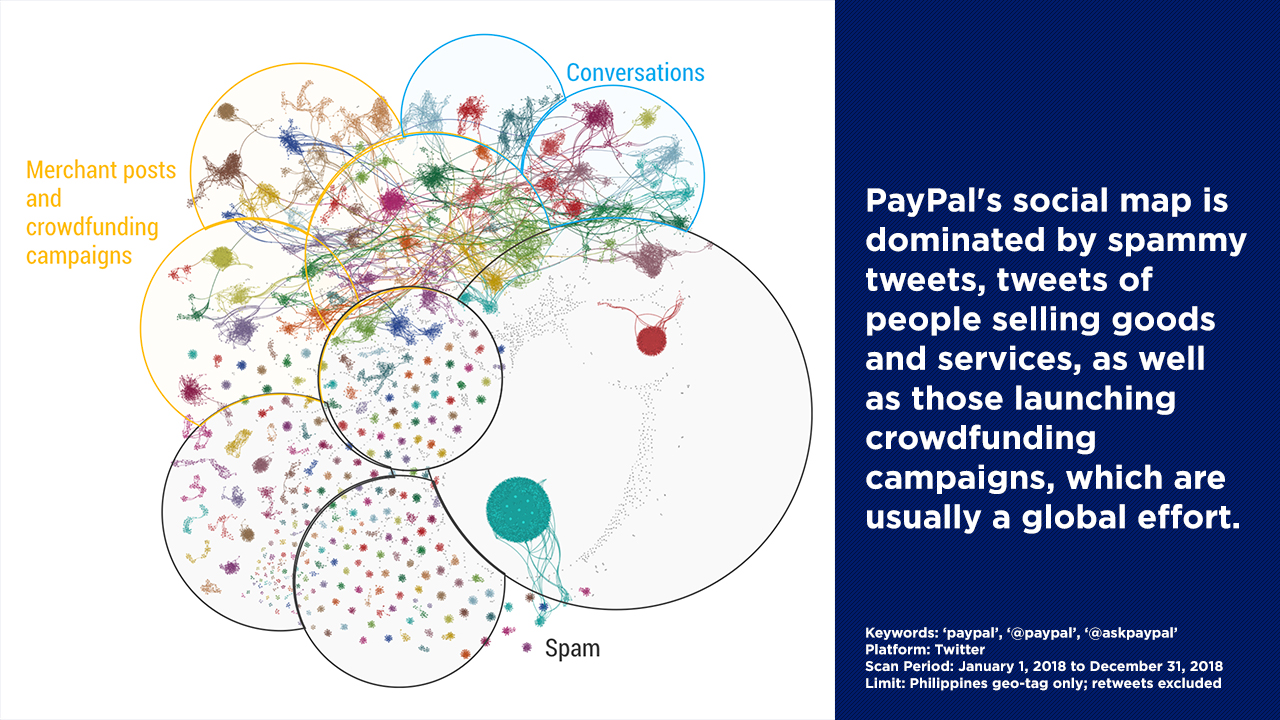

To know more about what people think of the payments apps, TheNerve used its natural language processing tool to monitor and analyze Twitter posts about them. The analysis spanned January 1 to December 31, 2018, with posts geo-tagged in the Philippines. Here’s what the team found.

GCash and PayMaya

Both GCash and PayMaya’s social maps are dominated by clusters of tweets about:

- inquiries, complaints, and other feedback (user conversations);

- press announcements and news articles;

- merchants and sales agents promoting streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify, which consumers can now subscribe to using the apps’ prepaid cards.

Announcements and news coverage are focused on partnerships with malls and brands that have started accepting the apps as modes of payment, as well as referral and cashback programs.

Zooming in on the user conversations, here are some key findings:

GCash

PayMaya

Coins.ph

PayPal

GrabPay

Survival of the deepest pockets

As the local race is still in a relatively early stage, there’s room for players to co-exist and share the market.

Having several e-wallet firms that spend for marketing campaigns raises consumer awareness and expedites adoption. At this point, players are fighting a common stubborn enemy: cash.

Today, cash still makes up 99 percent of Philippine transactions.

That means the market may remain fragmented, with more players potentially throwing their hat into the ring.

Yet having too many options can also hinder adoption. It’s tedious for a user to maintain dozens of apps.

In the long run, consolidation is bound to happen (we’ve actually seen a form of consolidation when Go-Jek acquired control of Coins.ph). In China, which is past the tipping point for mass e-wallet adoption, it’s evident: this is a sector where only a couple of players hold the majority of the market.

Players are expected to heavily burn cash to compete for market share so that means those with the deepest pockets will survive. It also means that profitability may be a long way off.

As e-wallet adoption grows, banks will be gravely affected. Apart from losing out to e-wallets in the unbanked market, existing transactions in their credit and debit card systems may shift to mobile as well. To stay relevant, they must determine how to compete and collaborate with new payment methods.

Seeing the onslaught ahead, the country’s lenders have led the talks to come up with a national QR code system with the goal of having the codes readable across financial apps – bank or non-bank. So this means that a merchant can display a single QR code that all payments providers will be able to scan. This kind of interoperability will level the playing field.

How the landscape will evolve when banks join the fray is definitely something to watch.

Thanks to TheNerve data team (Don Kevin Hapal, Ralph Nodalo, and Jamie Flores) for contributing to this report.

Read Part 1 | Why the Philippines has been slow to adopt e-wallets – and why that’s about to change

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Finterest] Is a digital bank safe, and how can you best use it?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/digital-banks-safety-may-11-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.