SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

WASHINGTON DC, USA – “It’s the first festival, the first big, big festival I’ve ever experienced,” Whammy Alcazaren told me in a conversation we had on Zoom. He was outside, in front of the Lincoln Square Center, after having just finished a dinner with other fellow filmmakers.

This was the venue of the New York Film Festival (NYFF), one of the most prestigious festivals in the US, housing powerhouse films such as the Palme d’Or winning Anatomy of a Fall and star-studded awards contenders such as Poor Things, Priscilla, and Maestro.

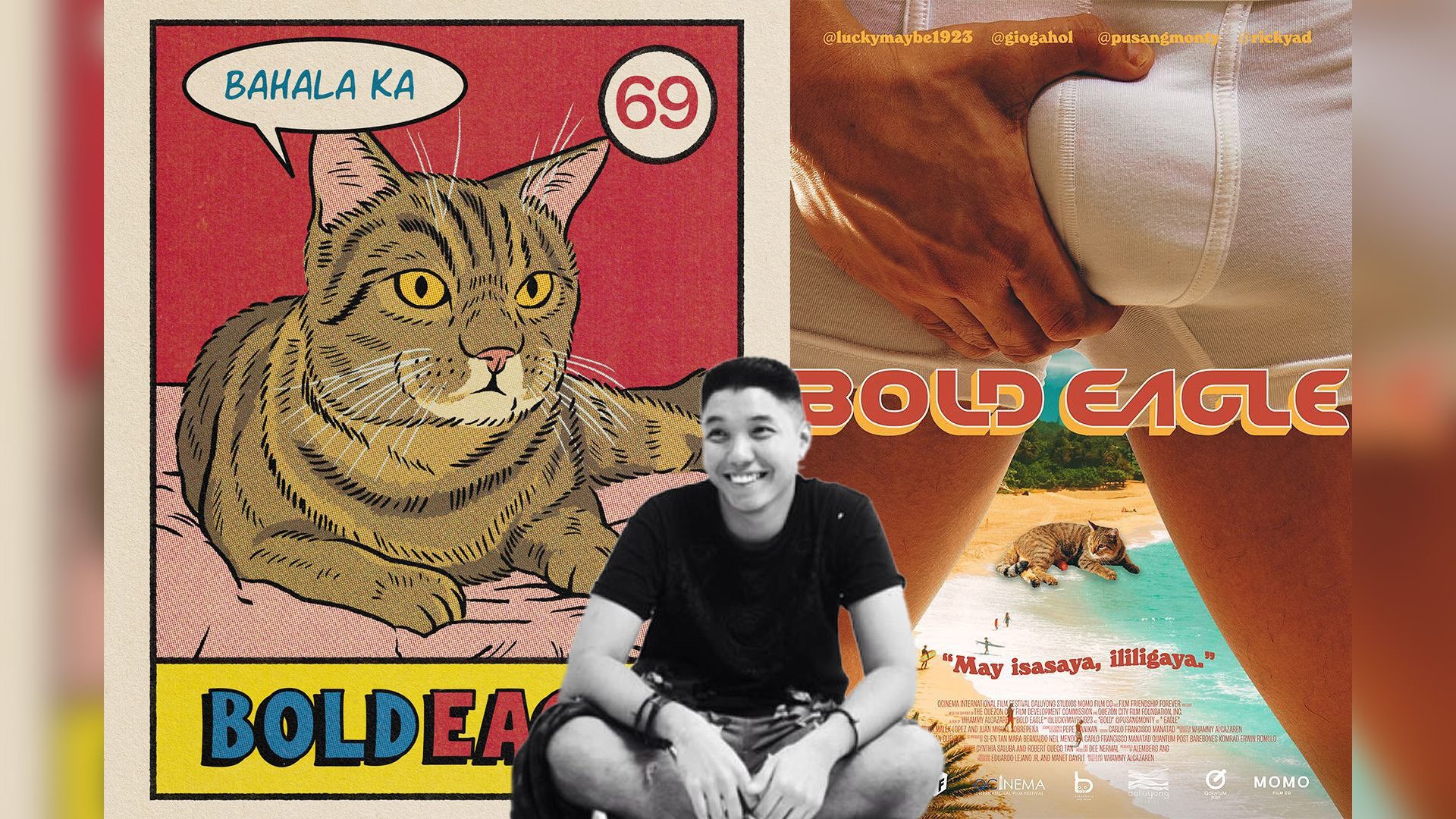

Part of NYFF’s “Currents Program,” which involves a showcase of “contemporary cinema with an emphasis on new and innovative forms and voices,” Bold Eagle stands out because it is, in no uncertain terms, “pornographic.” Through the perspective of Bold, the film delves into the world of “alter” accounts, uses erotic imagery to make us both laugh and ponder on personal and national histories, and who could forget, it also has a talking cat.

Bold, born in the QCShorts section at the 2022 QCinema Film Festival, has become quite the globe-trotter. It recently bagged the Best Short Film Prize at the Fantasia International Film Festival in July and was honored with the World Best Film award at the Binisaya Film Festival in September. Bold is poised to grace the screens of the San Diego Asian Film Festival and Jakarta Film Week later this year.

In my review of the film back when it premiered, I said, “In my humble opinion, it’s impossible to hate this film,” but after talking to Whammy, it seems that his film has caused quite the ruckus from audiences and certain censorship boards.

In this interview, Whammy and I talk about topics ranging from how his film attacks Marcos by using queer metaphors, making an internet-coded film, its curious connection to Maid in Malacañang, and why it’s important to make films for the 10 people who will appreciate it for what it is.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How was it like getting your film from QCinema all the way to the New York Film Festival?

It was quite unexpected given what the film is, and especially given the difficulty of showing it. So I knew that when we were submitting at the festival it would be quite a hurdle for something of this material to get shown, especially given that it’s not a very classic kind of film and it is a “porno,” as described by many people. But they did give a brief on the films here and I think they’re quite open and bold in their choices of film so we’re very happy. They’re very “New York” about their choices.

So the film was made while still in the pandemic stages. I want to ask, what was the impetus for pitching this bold, isolation-themed short to QCinema?

Actually, I already pitched Bold the year before, during the first year of the pandemic. But, it was a very different film. It was a horror film about the pandemic. But I got a year to really soak in the emotions of the pandemic and really get trapped at home so it was really this nice reflection of the time. When I pitched it to QCinema, I really pushed the idea that it was a pandemic film, but also that it’s really a continuation of Fisting (Never Tear Us Apart) that I wasn’t finished with. I really want to promote this new cinema of the Instagram story era because I really feel that it’s what cinema is going to be in the future. The language is always changing day by day.

So when I pitched, I said, “Yes, this is a pandemic film,” but also this is a rare opportunity to be able to showcase something very unique to what QCinema can allow, especially a government-funded festival, and most especially given the Marcos topics there. They knew it was about Marcos, and they were like, “Yeah, go!” The only question about it was, of course, MTRCB. How are we going to jump over what MTRCB will surely throw at us? And that’s why even the whole emojis thing was not something that we just did at the end, it was something that we had planned from the very beginning. They’re not ready to see all of the dick and all of the cum, so we’ll just put an emoji because it’s a bigger joke at the end of the day that they can’t beat us.

You talked about MTRCB and their relationship with this film. How was it like getting this film out in the Philippines and the compromises you made versus getting it out in New York? How was the difference in terms of censorship?

It’s heartwarming in New York so far because we’ve had all these meetings with other filmmakers, and when we tell them that it’s a porno, they get excited. They’re like, “Oh, what did you do? How will it be perceived?” And even if they hate it, they’re interested in seeing how the cinema is. Unlike the Philippines, when you say it’s a porno, they’ll already assume what it is without watching and I guess that’s my biggest issue with how it was received in the Philippines. We just assume what things are; we’re not ready to watch.

I don’t mind being hated for the film; it’s really part of it. But, the open discussion about it is even more important because it is artistic expression and it should be allowed. It’s so refreshing here that people are so open. They’re so ready to hate it, I know some people who already hate it (laughs).

In your previous film Fisting (Never Tear Us Apart), the opening features an underwear crotch shot of a man dancing. In this film, you also display all sorts of angles of male genitalia and orifices. So I want to ask, what made you want to be more “bold” in this film?

I think it’s really specific about the topic of content creators you have in the Philippines, the “alters” of the Philippines. I know not many people understand what an alter is. People just assume it’s porn on Twitter. But at the core of what an alter is the fact that they hide their faces and they want to be seen. There’s so much nudity in Bold because that’s what an alter is all about; it’s because you want to be seen, but you’re still shy to show your face because even in this intimate sense, you can’t really expose your true self. And that’s where the whole concept of Bold [comes from], the acceptance of the self, which is so complicated for anyone, queer or not.

That’s why for the opening butt shot, we have it uncensored because the body is so normal, because nudity is so normal. I wanted the audience, especially the Filipino audience, to feel that there’s nothing wrong with seeing that. It’s just a butt; he’s waking up.

I want to ask about the cat. It’s a very interesting thing to focus on as the companion of Bold throughout the film.

Actually, the talking cat is the actual ending of Fisting. At the end, the child character talks to the cat and they have this existential conversation about his identity and masculinity, so that’s really the seed of how we started Bold. Trapped in the pandemic in my mom’s house, we had 20 cats. As you can see in the film, who doesn’t want to be a cat who doesn’t care about the pandemic and they’re quite happy just lazing around, unbothered by everything around them?

The cat you see in the film is actually the cat of our actor. So when we were searching for alter actors, we would ask them if they would be comfortable on camera, comfortable with their identity. And then the last question is, “Do you have a cat?” It was not easy; we shot so long because of the cat. The montage of the cat took half a day because he’s a cat, so how would you shoot a cat? So we will never be shooting with animals again.

I wanna talk about those old vintage family photos you have scattered throughout the film. What made you want to intersperse these images of seeming childhood innocence with old porno magazines and images of men in wrestling and basketball?

It’s really like when you were a kid and then your dad is trying to butch you up with these things. I’m from an all-boys school, so we would be into wrestling, we would have to play basketball. It’s such an understandable image of masculinity that anyone would understand. Like, a queer boy is there; we’re gonna throw a basketball at them. It’s a moment of terror.

I wanted to keep the imagery quite simple; this is how the language of the internet really comes into play, where all these simple and very understandable things, anyone can understand. If we think of memes and TikToks, these are made by people with no specific language; these are all images. So, at the core, you imagine that these are things that are common with any race, any gender. It’s like the “Collision Montage” where you have “A + B = C,” so that’s the basic formula of how we did it. And that’s how I feel “internet language” is right now. If you think of it as film theory, that’s how memes work. You trickle it down to basic things, and across the board on the internet, people will understand. That’s how we designed the film in terms of its imagery, especially in the montages.

How does it feel premiering a BBM-era film with very unique digs at the Marcos family less than a year into his term?

When we pitched this film back then, hindi pa siya (it wasn’t yet an) anti-BBM film because he didn’t win yet. But when he got in, that’s when we adjusted the script. Sabi nga ni Ma’am Sari [Dalena], “Film is always political,” especially the landscape of the Philippines. That’s what we learned in UP. So it [the film] really has to take a stand, and, of course, I will only do it in the way I want to do it. In my perspective, we will do this in a way that is funny, because I know not many people will want to do it in this way, to sexualize Bongbong, to make him queer. So when we were writing this, the way I explained it to my crew was that Bold Eagle actually was the biopic of Bongbong as a queer child trying to seek the acceptance of his father, trying to fill the shoes of his father.

There’s many layers in the film, in the narrative, in the language, and even in the song “Bagong Lipunan.” My scorer is Erwin Romulo and when I met him I told him, “Okay, I really want the main recurring song to be a parody of Bagong Lipunan.” We have three versions. We have a very sappy, cheesy, acoustic version. We have the normal version that plays at the end of the film. And we have the budots version. When I was writing the song for the film, it was really meant to be the “sadboi” version. We tried to make sure the film as a whole would survive aside from the BBM things. That’s why you see a lot of Hawaii, specifically, and we have images of Imelda in the background. It’s so funny to me that the narrative of the film is that, “I [Bold] can’t fulfill what the expectations of my father is, so I just escape to Hawaii,” which is what his dad did, too.

Suffering in the film has taken on an erotic quality, blurring the line between hedonism and fascism. There are lines like “Saktan mo pa ako, gusto ko ‘to,” or “Sabihin mong pinapasarap kita, Daddy.” Are you, in a way, commenting on this toxic paternalist psyche Filipinos have with their authority figures?

It is queer culture, but it is also BDSM culture. That’s how we find satisfaction na sinasaktan tayo (when we get hurt). And then, in BDSM culture, that’s how you feel powerful, by being hurt, because you’re switching the sides of it. That’s why, especially in the climax scene, it’s a phone sex scene where Bold is saying to the father, “Hurt me more, hurt me more,” but also at the same time asks, “Do you like what you’re doing to me? Am I so good?” This is how we deal with our mental struggles and that’s how BDSM is. It’s really an escape from reality and that’s how we keep ourselves grounded. In the real world, you feel so powerless and because of these sexual acts, you regain power and feel good about yourself. That’s why in classic BDSM stories, you see the businessman being api (oppressed), and the ones who are api being so strong.

I was reminded of Cabaret (1972) through your film. Especially that BDSM-like military uniform near the end.

Side note, the costume that he wears, the military outfit, we got it from the supplier of Maid in Malacañang. It’s the costume of General Fabian Ver. So [it has] the same medals; I hope they see the medals. Apparently, there’s only one supplier for stuff like that.

One of the weirdest 2022 Philippine film crossovers. Maid in Malacañang and Bold Eagle.

(Laughter)

I remember you said, after the premiere of Bold Eagle that, “dreams are expensive,” referring to your production of the short film. And that made me ponder on how hard it is to really make films you want despite already having a proven track record to your name. I was also reminded of Erik Matti’s recent post about the local film scene becoming more about patronage and not just about making the films we want. In this case, what does the success and recognition of Bold Eagle mean for the local film scene moving forward?

I think it’s more of a lesson that you shouldn’t care so much anymore what the people in Manila think, because everyone is so concerned with audience like, “Oh, yung box office.” I’m not part of that conversation. So when people hate Bold, they’re free to hate it, but cinema, for me, is entertainment. All cinema is entertainment. All cinema is a Star Cinema film for someone. The success of Bold is very good for me since more people are watching. But at the end of the day, people who used to watch this thing are still the 10 people that I still make movies for, because they’re the 10 people who see my film as Vice Ganda.

If you look at the history of cinema, it was entertainment from the very beginning. It’s 10 seconds of a train, and that’s what TikTok is now. When we go back to Manila and even if it’s hated here, at least more people will hopefully think that cinema is not just this, it’s not just what you see in Cinemalaya, it’s not what you see in QCinema. Cinema is not just one thing. It’s for everyone. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.