SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

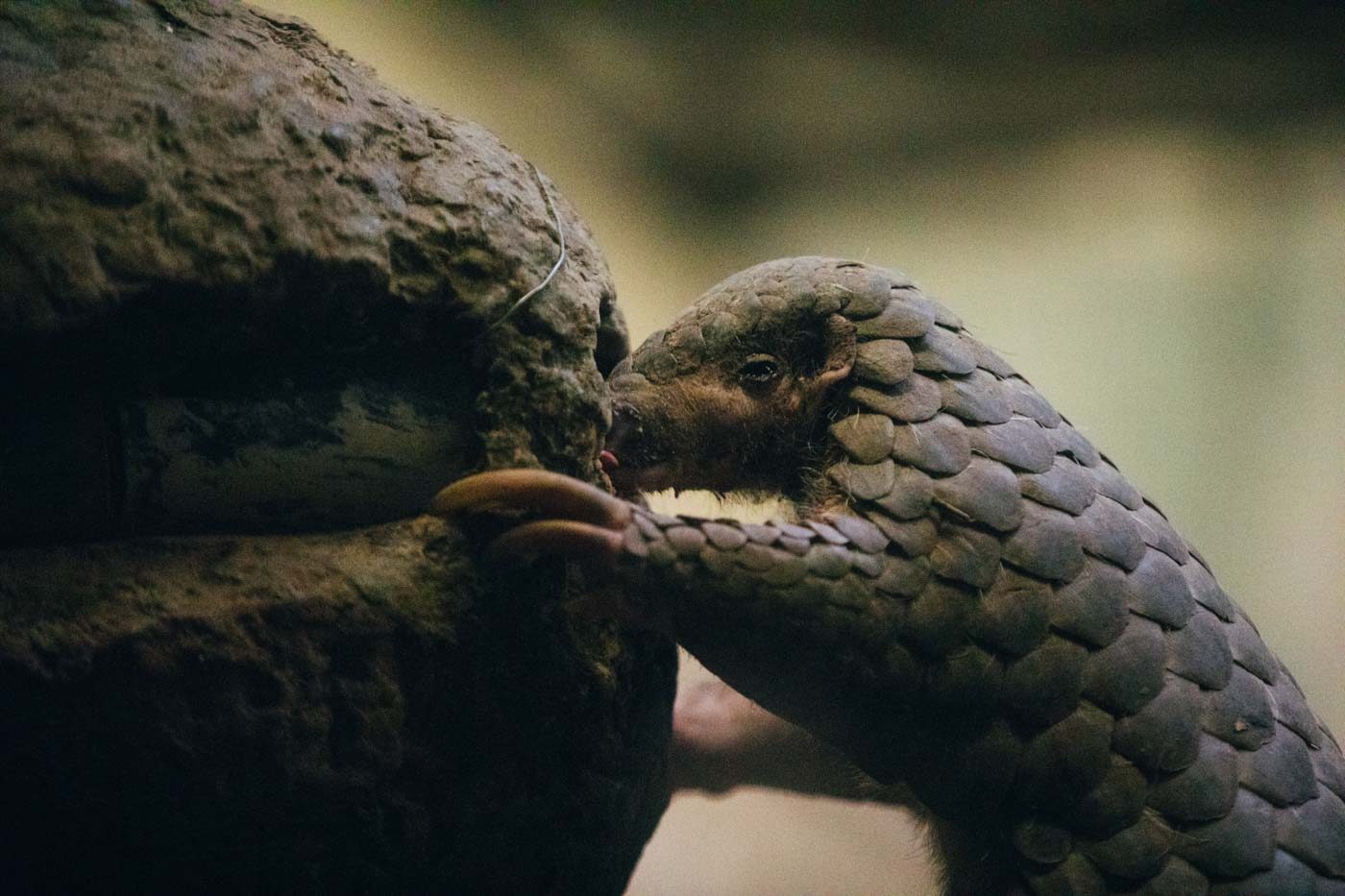

Pangolins: The multimillion-dollar mammal

The world’s most trafficked mammal is a solitary anteater resembling an artichoke: the pangolin. Prized for its scales, particularly for traditional medicine in China, this quiet animal is at the center of a sophisticated, multi-million-dollar supply chain across Africa and Asia, run by networks of criminal syndicates.

The Global Environmental Reporting Collective, formed in early 2019, chose the pangolin trade as its first focus for in-depth investigation. More than 30 journalists from 14 newsrooms reported in Africa and Asia, conducting dozens of exclusive interviews and even going undercover. The results are being published here as The Pangolin Reports.

“Roughly 50 tons of illegal African pangolin scales have been seized globally in the last 4 months,” estimated Peter Knights, the CEO of WildAid, an advocacy group. “In shipments that contain both pangolins and ivory, pangolin scales have now surpassed the volume of ivory.”

High demand has made the pangolin the most illegally traded mammal in the world, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). All 8 subspecies of the shy animal are threatened with extinction, scientists say. And when pangolins disappear, so does the ecological balance in their natural habitats.

“In the 21st century we really should not be eating species to extinction,” Jonathan Baillie, a leading expert, said in 2014. “There is simply no excuse for allowing this illegal trade to continue.” In the preceding decade, more than a million pangolins are believed to have been hunted, the IUCN estimated.

A global ban on the trade that came into effect in January 2017 did not turn things around. Record numbers of pangolins have been seized so far this year, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), an advocacy organization.

In February, a 30-ton seizure in Sabah, Malaysia, was the largest recorded so far. In April, the Singapore authorities intercepted 12.9 tons of scales, a record seizure equivalent to 36,000 pangolins. A few days later, Singapore confiscated an additional 12.7 tons. In July, another bust led to the discovery of a 11.9-ton shipment, making 2019 a record year.

Global seizures have surpassed the 2018 figures by a wide margin, according to the EIA. Its researchers estimate that an equivalent of 110,182 pangolins have been confiscated by law enforcement this year so far – a 54.5% increase compared with last year.

One reason is the increased awareness by law enforcement, said Darren Pietersen, the director of research and conservation at Tikki Hywood Foundation. “Various research articles suggest that this increase is at least in part a genuine increase in the number of pangolins being poached,” he said.

“Only a tenth of trafficked wildlife is actually intercepted, according to one Interpol estimate.”

Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of smuggling is likely to continue undetected, our reporting suggests. Only a tenth of trafficked wildlife is actually intercepted, according to one Interpol estimate. (READ: Six facts we didn’t know about the pangolin)

Our journalists traced the illegal trade routes from roadside markets in Cameroon and elsewhere to intermediaries and traffickers in Nepal back to China. The following chapters will provide insights into a shadow economy that has thrived out of sight. Without intervention, these actions will drive the animal to extinction.

Despite the scale of the trade, little is actually known about it, even among prosecutors and law enforcement officials in its key market: China.

China: Tons of demand for ‘commercially extinct’ species

Outside the gates of a warehouse in southern China, a middle-aged man surnamed Zhang at first showed no interest in talking to us or answering questions about his business dealings in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

His mood changed when we mentioned pangolins. “Do you have supply?” he said. “Come to our office, let’s talk about it more.”

Zhang works in the supply department of a TCM producer in Shantou, Guangdong Province. “So far this year, we’ve used several tons of pangolin scales,” Zhang said. “We need at least a few hundred kilograms a month.”

“We ordered a ton of scales last month, but it hasn’t arrived yet,” he said, adding that they would also sell unprocessed scales to other pharmaceutical companies.

Our reporters reviewed more than 400 court decisions in criminal cases in China related to the illegal trade in pangolins from 2005 to 2019. In only a few of the court cases we studied were prosecutors able or willing to retrace the smuggling routes to their origins, like Indonesia and Nigeria.

The numbers of pangolin seizures are rising, not only in China, the primary market, but also in transit hubs such as Vietnam, Singapore, and Hong Kong, according to EIA figures. Even in those places, the origin of the goods remains unknown for the vast majority of cases.

Breeding and keeping pangolins has proved difficult. China has an intransparent system that allows for the continued consumption of pangolin stockpiles for TCM. Due to the high demand and limited regulatory oversight, many suppliers rely on cheaper, illegal imports.

This was why we visited Zhang, undercover, at his factory in southern China. We wanted to know where his scales came from.

Zhang insisted that his company was willing to pay a surcharge to source only legal scales, even though they could cost up to twice as much. “Price is not a problem,” he said.

His company, among others, makes TCM concoctions out of raw pangolin scales in industrial quantities. We later reached out to the company, asking them about the origin of their scales. They declined to comment.

“Where do these millions of pangolins come from if there are almost none left in China?”

But his statements left us curious. If a medium-sized company like his needs tons of scales, where would larger pharmaceutical companies source their pangolin scales? Where do these millions of pangolins come from if there are almost none left in China?

China’s pangolin population has dropped over 90% from the 1960s to 2004 due to massive poaching for its meat as a delicacy and its scales for medicinal use. The Chinese pangolin has been “commercially extinct” since 1995, researchers say.

The profit margins we found are astounding. Scales bought for as little as $5 per kilogram in Nigeria can be resold for up to $1,000 in China, according to traders we interviewed in China. If mixed with legally acquired scales, their price can be as high as $1,800 per kilogram.

Who would want pangolin scales? According to some TCM practitioners, pangolin scales can cure a host of ailments, including inflammation and poor lactation in new mothers, and even impotence and cancer.

Dr Lao Lixing, the former director of the School of Chinese Medicine at The University of Hong Kong, said that there is no scientific research that supports the claim that pangolin scales have healing properties.

He said that TCM practitioners in Hong Kong and mainland China have largely stopped prescribing medications with pangolin scales, but pharmaceutical companies have continued to produce drugs with the scales. “It’s a matter of market and profits,” he said. “To further the ban on pangolin use in Chinese medicine, we need more public education and concerted efforts by the TCM sector.”

“TCM professionals need to speak up to defend the good name of the Chinese medicine,” said Dr Lao, who speaks regularly at international conferences to advocate replacing animal ingredients in TCM with plant-based substitutes.

Although its medicinal properties are unproven, mostly Chinese patients appear to be consuming literally tons of these products. The problem is that we don’t know how much.

“There continues to be a complete lack of transparency on the quantities of pangolin scale stockpiles held by the government or private entities in China,” Chris Hamley, a senior campaigner on pangolins at EIA, wrote in an e-mail. “There is also no information on the estimated quantity of pangolin scales consumed by the Chinese population over a specific time period.”

“The recent string of multi-tonne ‘mega’ shipments of pangolin scales detected by law enforcement agencies in Asia demonstrates that the supply of pangolin scales from historical stockpiles does not meet demand.” (To be continued.) – Rappler.com

This is part of The Pangolin Reports’ “Trafficked to Extinction,” a global report investigating the illegal wildlife trade of pangolins across Asia, Africa and Europe.

TOP PHOTO: A pangolin rescued from traffickers in Vietnam recuperates at a rehabilitation center run by NGO Save Vietnam’s Wildlife. Screenshot courtesy of Centre for Media and Development Initiatives.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.