SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines — It is very easy to judge someone we do not know.

This seems to be the case for some people in the Philippines, which is home to around 100 million people, 12%-15% of whom are indigenous peoples (IP).

Under Philippine law, IPs are defined as a “group of people or homogenous societies identified by self-ascription and ascription by others, who have continuously lived as organized community on communally bounded and defined territory, and who have, under claims of ownership since time immemorial, occupied, possessed and utilized such territories, sharing common bonds of language, customs, traditions and other distinctive cultural traits.”

Despite national policies protecting IPs, many Filipinos still view them not as equals but as outcasts or inferiors.

Among the country’s IPs is the Mangyan, a collective term for the 8 indigenous groups in the island of Mindoro: Iraya, Alangan, Tadyawan, Tau-buid, Bangon, Buhid, Hanunuo, and Ratagnon. There are over 100,000 Mangyans, according to the Mangyan Heritage Center (MHC), comprising 10% of Mindoro’s total population.

The Mangyans originally settled along the shores of Mindoro, but were eventually pushed into the uplands. They were first forced to leave their coastal homes during the Spanish era, then again during succeeding episodes of colonization. After World War II, more of their lands were either occupied by outsiders or destroyed by loggers and developers.

Since Mangyans live far away from Tagalogs, misunderstanding between the two erupted. Some of the lowlanders called Mangyans dirty and uncivilized. Meanwhile, other Filipinos tend to mystify the Mangyan, viewing their society as a mere exhibit.

To combat discrmination, the MHC urges Filipinos to bust the following myths on Mangyans:

1. Mangyans destroy the environment

The Mangyans, alongside other IPs, have long been falsely accused of destroying nature by engaging in kaingin (slash-and-burn). The Mangyans, however, are very much in tune with nature. Their culture tells them to care for forests and lands they inherited from ancestors.

“Alam po namin kung paano ginagalang ang kagubatan (We know how to respect forests,)” said Aniw Lubag, president of Pinagkausahan Hanunuo sa Daga Ginurang, a people’s organization for the Hanunuo Mangyan.

“Sabi ang Mangyan, walang pinag-aralan, walang alam sa agriculture. Pero di po totoo ‘yan (They say Mangyans are uneducated, know nothing about agriculture, but that’s not true),” he added.

The Hanunuo Mangyan’s shifting cultivation, also known as swidden farming, has been extensively studied in the 1950s by anthropologist Harold Conklin of Yale University. Conklin stressed that such practice is different from the kaingin done by non-Mangyans, in which fire is not prevented from spreading into other vegetations.

In the 1990s, a follow-up study by Hayama Atsuko found that the Hanunuo Mangyans’ farming practices “have prevented land deterioration in spite of the fact that forest land degradation is now evident in their territory due to various factors,” according to the MHC.

In 2009, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) published a paper concluding that shifting cultivation is not a major cause of deforestation. In Asia, the main causes of deforestation and carbon emission are “intensification of agriculture and large-scale direct conversion of forest for small-scale and large industrial plantations.”

“When they clear, there’s a buffer zone so the fire won’t spread,” explained Emily Catapang of MHC. “They cover trees with saha ng saging (banana trunk) so they won’t be affected.”

Their swiddens are like forest replicas with its own vegatations, Catapang continued, “‘They don’t just plant rice, it’s diverse. A fallow period also allows the land to rest and recover.”

“Their agricultural practice is really organic, they also don’t use pesticides,” she added. “Deforestation here is not caused by Mangyans but by loggers.”

Parents also teach their children to plant and to never cut down big trees.

2. Mangyans are beggars

The Mangyans are an industrious people. Some Filipinos mistake them for beggars during Christmas season when in fact, they are selling self-made products like walis tambo (broom), duyan (hammock), bags, and accessories.

Mangyans mostly live on subsistence farming, which means they eat what they plant. Their harvests are only enough for the family. Sometimes surplus crops are sold for money, but with only small returns.

For additional income, women create and sell various handicrafts like woven textiles, baskets, and beaded items.

The MHC helps sell these products at prices set by the Mangyan themselves. Profits are used for MHC’s cultural program and scholarships for Mangyan students.

Some Bangyon Mangyans, however, do come down from the mountains during Christmas season, “Para mamasko since they know that the Christians are more generous during the Christmas season. It became a tradition,” said Catapang. Some of them carry products with them, others do not.

“But they just do this during the Christmas season, they return home after the holidays,” she added.

3. There are “white” Mangyans

There is one Dutch anthropologist who married a Mangyan woman, according to Catapang, but it is not true that there is a line of white or Caucasian Mangyans. Some Mangyans, however, have fair complexion.

4. Mangyans have tails

As ridiculous at it sounds, some Filipinos believe this myth.

The “tails” are actually part of the Mangyan’s bahag. “‘Yung tali sa likod ng bahag nila, kapag dumumi nagmumukhang buntot (When the rope at the back of their loincloth gets dirty, it looks like a tail),” said Catapang.

5. Mangyans are illiterate

Some Filipinos still call Mangyans mangmang (illiterate), dismissing the long and rich history of Mangyan script and poetry.

Rhythmic poetic expression with a meter of 7 syllable lines and rhythmic end-syllables

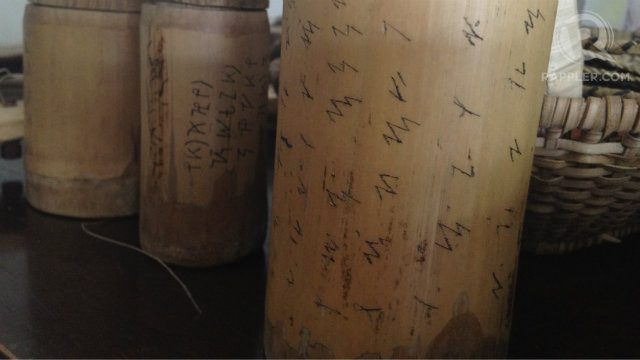

The Mangyan syllabic script is a pre-Spanish writing system which is still used and taught in schools until today. It has been declared as a National Cultural Treasure in 1999.

Meanwhile, the traditional poetry of the Hanunuo Mangyan is called Ambahan. The poems tell various stories ranging from childhood to friendship, love, old age, and death. It is usually written on bamboo.

Over 20,000 of these poems have been documented by Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma, who is married to a Hanunuo Mangyan and has been living with the Mangyans for more than 50 years now. Postma recored the ambahans in casette tapes, which were then digitzed by the MHC. They are currently preserved at MHC library in Mindoro and at the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

The ambahan can be presented as a chant. Some parents teach their children values and life lessons through songs. Aside from the Hanunuo, other Mangyan tribes also have their own literature and folktales.

Unlike in the past, many Mangyans are now able to study. Poverty, however, remains a hindrance for many.

Such myths on the Mangyans not only perpetuate discrimination, but also diminish the many roles of IPs in agriculture, education, history, art and culture. What other myths do we need to bust? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.