SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

(Part 1 of 3)

- PART 2: Duterte government moves to get activists out of party list

- PART 3: Principles and compromise: How Makabayan survived under Duterte

At a glance

- Progressive groups affiliated with the Makabayan bloc in Congress continue to face increasing harassment and intimidation under President Rodrigo Duterte

- Rights group Karapatan documented 1,126 activists and grassroot organizers arrested and detained, while 414 were killed between July 2016 and June 2021.

- Many community organizers and their colleagues resolve to lie low for safety not just for themselves but also their families.

- They fear the attacks will intensify as the election period approaches.

Very cautious

Lai Consad should have been a principal now if circumstances were normal and if the Philippines isn’t ruled by a leader hell-bent on squashing dissent.

The 54-year-old secretary-general of Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) in CARAGA has all the qualifications. She passed all the prerequisite examinations, aside from having decades of teaching experience under her belt.

But in June 2021 Consad didn’t think twice about rejecting the offer to be a public school principal. She said she wouldn’t be able to meet the demands of the position since she was very cautious – “dahil sa imminent danger sa buhay ko (because of the imminent danger to my life).”

Consad was arrested and detained for two days in March 2021 on charges of attempted homicide in relation to an alleged New People’s Army (NPA) encounter in Agusan del Norte.

At the time of her arrest, she had been assistant principal at San Vicente National High School in Butuan City for two years and a special education (SPED) teacher for more than a decade.

Consad has been with ACT since 2015, becoming a regular figure in regional protests calling for better wages and benefits for teachers. With her public involvement came a series of harassment and consistent surveillance from what she assumed were state agents. She recalled being invited numerous times to a nearby military camp to “clear her name.”

“I thought to myself this is the result of my activism, of my being an ACT official. This is their way to silence me and to stop me from joining rallies,” she told Rappler in Filipino.

Worsening situation

Consad’s experience reflects the general situation of mass organizations affiliated with the Makabayan bloc at the House of Representatives, whose members Rappler interviewed.

The Makabayan Bloc in Congress includes Bayan Muna, Gabriela Women’s Party, ACT Teachers, and Kabataan Partylist.

They fear the attacks on their organizers will intensify as the May 2022 polls near. Gabriela and Kabataan face petitions seeking to cancel their registration. (READ: Which party-list groups is NTF-ELCAC trying to get disqualified?)

Many lives are put on hold and constantly in danger as the Duterte government continues its massive anti-communist insurgency campaign. The state blurs the line between activists and communist rebels, evident in its red-tagging spree led by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) and its supporters.

The United Nations (UN) rights office defines red-tagging as “labelling individuals or groups (including human rights defenders and non-government organizations) as communists or terrorists.”

The implementation of the anti-terror law further heightened the fear of arrests and persecution among progressive groups. (READ: Are activists at risk of arrest, being designated terrorists? They’ll rely on good faith.)

Rights group Karapatan has monitored at least 1,126 individuals affiliated with progressive groups arrested and detained under the Duterte administration, as of June 2021.

At least 2,725 were also arrested but not detained in the same period.

The total number of arrests made in line with the government’s anti-insurgency campaign continues on a steady rise since the failure of the peace talks in 2017. (READ: The end of the affair? Duterte's romance with the Reds)

There was a noticeable spike in the number of arrests with detention between July 2019 and August 2020, with at least 1,623 recorded incidents by Karapatan.

This huge increase was recorded in the latter half of the period when the coronavirus pandemic began and peaked in 2020. This reflects the observation of many human rights groups that the government took advantage of the health crisis to further commit violations.

Consad was released on bail two days after her arrest in March 2021. The case against her was then dismissed in July 2021. Yet, she has not returned to her home and embrace normalcy again with her two children.

“I frequently change houses because I carry the weight of their threat that they will kill me and my family if they find out I am still in Butuan or in CARAGA. I fear more for my family, not really for myself, that’s why I haven’t been home,” Consad said.

Deaths all over

Consad’s fear is not unfounded. The Duterte government has left such a bloody trail that many fear the extent state agents will go just to satisfy the orders of the leadership. In many cases, the intimidation does not stop with just arrests.

In a 2020 report, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) said that the Duterte administration "created a dangerous fiction that it is legitimate to hunt down and commit atrocities against [human rights defenders] because they are enemies of the State."

Activists and human rights defenders, the commission said, live a “grim reality” with the constant delegitimization of their work that results in systematic attacks that place their “the life, liberty, and security… at great risk.”

This report is reflected in the number of activists killed since 2016. Rights group Karapatan recorded 414 activists and grassroot organizers killed between July 2016 and June 2021. At least 497 people, meanwhile, faced attempted killing in the same period.

The number is consistently rising over the years, with a noticeable spike between July 2017 and June 2019, where 198 deaths were recorded in a two-year period.

In 2018, the United Nations listed the Philippines as one of 38 countries where governments subject activists to "an alarming and shameful level of harsh reprisals and intimidation."

More than 50 deaths were recorded each in Bicol, Davao Region, Central Visayas, and Western Visayas between July 2016 and June 2021.

Activist Zara Alvarez was one of the 53 killed in Western Visayas. She was shot dead in Bacolod City in August 2020. (READ: Zara Alvarez asked for protection, but she died before the court could give it)

MIMAROPA and Calabarzon, meanwhile, saw 34 deaths, as of June 2021.

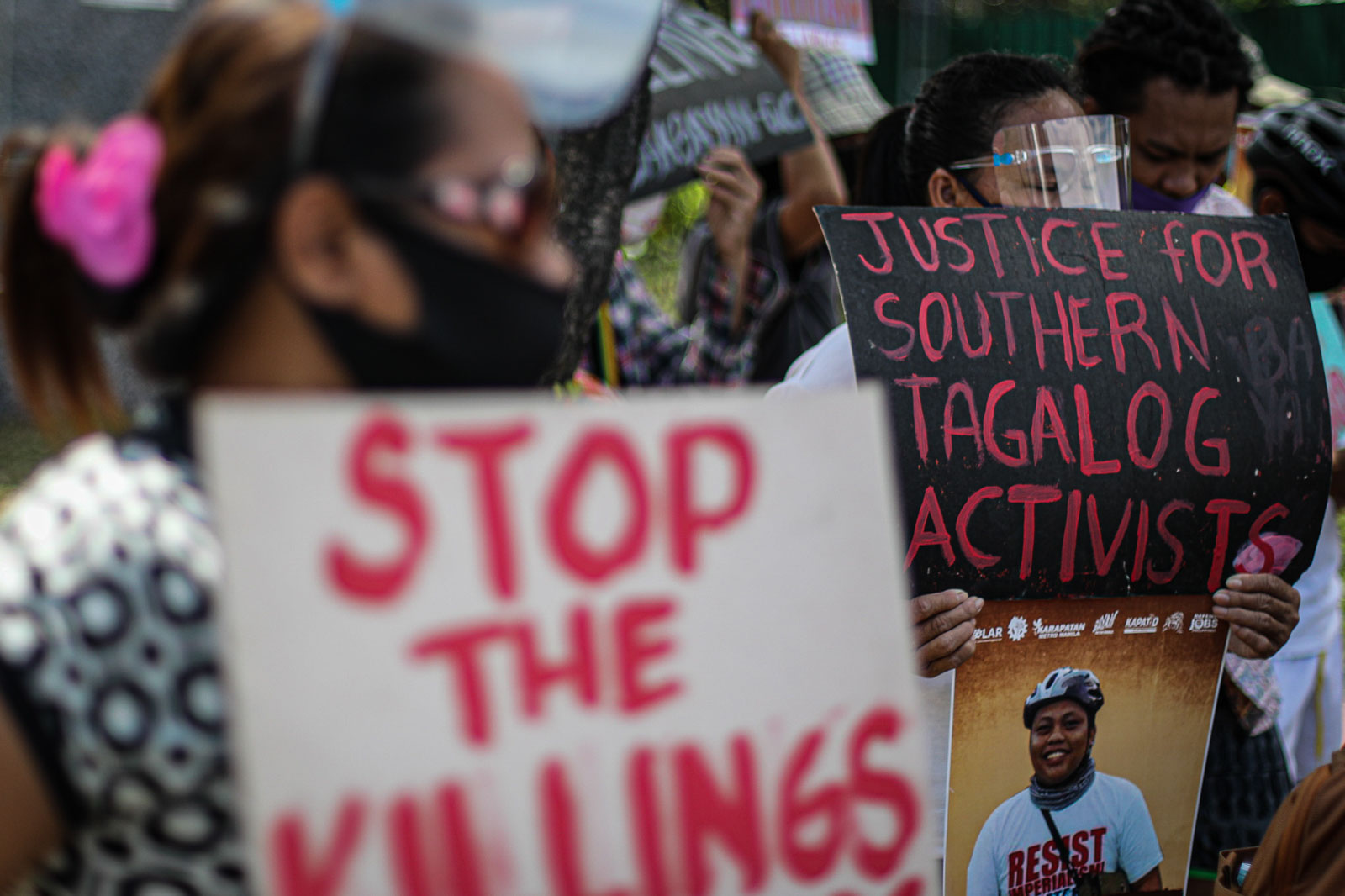

At least 10 activists were killed in the region in March 2021 alone. Nine were killed during the "Bloody Sunday" raids by police and military in Calabarzon on March 7. Three weeks later, labor union leader Dandy Miguel was gunned down on March 28.

Tonet Amorado, spokesperson of Bayan Muna Southern Tagalog, said the grave situation in their region was so palpable, especially with many people they worked and marched on streets with ended up dead in the past years.

“We acknowledge that there has been a decline [in organizing efforts] since our leaders and organizers fear not just for themselves but also their families. How can we address the issues faced by the masses if our leaders, organizers, coordinators all flee their homes?” Amorado said in Filipino.

There were cases when they weren’t able to respond to incidents of harassment in communities, to avoid possible further violence. Amorado herself received threats so harsh that her family often urged her to stop doing activist work.

“I got scared because there’s info that my photo is in the [police] camps. There’s so much fear so I left home because I didn’t know what would happen to me,” Amorado said.

The violence and impunity faced by progressive groups prompted leaders and families of those slain to ask the Supreme Court (SC) to intervene. (READ: CHR: DOJ-led panel 'slow' in solving extrajudicial killings)

In a letter submitted to the SC in May 2021, the groups "earnestly ask that these incidents of attacks and concerns be seriously taken into account in the process of formulating and issuing any preventive and remedial steps to address the worsening state of human rights in the country."

Spilling over into communities

According to Nica Ombao, regional coordinator for Bicolana Gabriela, many of her colleagues were forced to lie low or leave organizing work due to the constant threats to their lives.

She said she couldn't blame the members who had gone out of sight, fearing for their lives.

“Kasi napakalakas ng paniniktik dito sa Bicol – sinusundan sila, binabantayan sa labas ng bahay, at nakakatanggap ng actual threats sa tawag at text messages,” she told Rappler.

(Surveillance has intensified here in Bicol – they are being tailed, watched from outside their homes, and they receive actual threats through phone calls and text messages.)

At least 58 activists have been killed in Bicol since 2016.

Two activists were killed by policemen in Guinobatan, Albay, after they were caught spray-painting an anti-Duterte slogan on July 26, hours before Duterte's last State of the Nation Address.

In May, two activists – Anakbayan Naga chairperson Sasah Sta. Rosa and Bayan Bicol spokesperson Pastor Dan Balucio – were arrested in separate raids in Bicol for alleged illegal possession of firearms and explosives. Their groups alleged the evidence was planted.

But beyond threats to their lives, Ombao said, they also fear for the communities they work with, especially with rampant militarization in many far-flung areas under the government’s anti-insurgency campaign.

She told Rappler that they always saw either the police or military lingering in areas where they held feeding programs or other relief operations, especially in Albay.

“You really can’t shake off the fear that the threats might spill over into communities we work with,” Ombao said. “Their willingness to continue working with us comes from the fact that we constantly hold discussions with them about what we do.”

With the coming May 2022 elections compounded by efforts to discredit Makabayan bloc and its affiliated mass organizations at the national level, Ombao said they were “preparing for the worst case scenario” of continued cases and deaths in the Bicol region and elsewhere.

“Duterte is desperate to remove Makabayan from Congress,” she said in Filipino. “He’s very desperate to stay in power.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[New School] Tama na kayo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-tama-na-kayo-feb-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=290px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.