SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

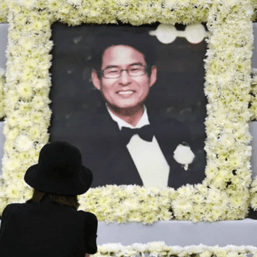

MANILA, Philippines – Alex, not his real name, is a veteran journalist based in Metro Manila. After the killing of broadcaster Percy Lapid, he said the police started to look for him – not because he was involved in the case, but because the cops said they wanted to secure him.

On October 3, Lapid was gunned down by still unidentified assailants in Las Piñas City. Two days later, on October 5, Alex said cops went to their house, but failed to see him.

When cops did not find him, they started calling him: “Nang hindi ako makita, nakuha number ko sa barangay, then ‘yon, panay tawag (When they did not find me, they got my number from the village, then after that, they started calling.)”

According to Alex, the police called to invite him to their headquarters for a dialogue between the cops and the media.

He added the police said they were doing it to protect journalists within their area of responsibility. In the program, the police will ask for the contact details of journalists or visit their houses to invite them to a caucus to talk about how cops can help protect journalists.

Even though it was meant for security purposes, Alex said he was not comfortable with how the cops were implementing this program.

“Alam mo, ayaw ko ng ganyang sistema, nakakatakot ‘yan. Kasi nalalaman ng mga pulis location ng house mo. Pa’no kung sila tumarget sa’yo? (You know, I don’t like that system, that’s scary. Because the police know the location of house. What if you became their target?),” Alex said.

In a statement on Saturday, October 15, National Capital Region Police Office director Brigadier General Jonnel Estomo confirmed the visits and said they were doing these to reach out “to our friends from the media especially those who have been receiving threats.”

Estomo adds, “the NCRPO is concerned about the safety and welfare of our media men, we confirm that it was our gesture to know if there are threats on their lives and of their families in order to assess the security assistance that we have to accord to them.”

In a statement released on October 7, the (NCRPO) said they were conducting a dialogue with journalists to preempt violence against journalists, like in Lapid’s case.

“To preempt similar event to happen in the future, the National Capital Region Police Office through its Regional Director PBGen. Jonnel C. Estomo directed all District Directors and Chiefs of Police of the five police districts of NCRPO to initiate a dialogue to all journalists, broadcasters and media practitioners in their respective areas to determine imminent threats if any and address their security concerns accordingly,” the NCRPO said.

The NCRPO said Estomo’s guidance also includes security detail if needed, depending on the gravity of threat against a journalist. In their statement, the Metro Manila police added, the program was based on pronouncement of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to ensure media safety and the directive of Philippine National Police (PNP) chief General Rodolfo Azurin Jr.

On October 11, the Southern Police District held a dialogue and threat assessment with journalists covering their area. The Eastern Police District also organized a same event with journalists covering the cities of Pasig, Marikina, Mandaluyong, and San Juan.

Same experience

JP Soriano, a GMA News reporter, also shared similar experience like Alex’s. Soriano shared in a series of tweets that a cop, who was not wearing proper police uniform, visited his private residence.

Like in Alex’s experience, Soriano said the cop told him that they were doing it to assess threats on journalists. The same cop also looked for the address of another journalist, who happened to be Soriano’s neighbor.

Soriano said he called Marikina Mayor Marcy Teodoro and the local chief executive confirmed that the visit came from the PNP’s directive. The GMA News reporter added that Teodoro told him the PNP did not coordinate with Marikina City.

Mark (not his real name), another journalist based in Marikina City, said he was also visited by cops in his house. He said Teodoro also confirmed to him that the program was being implemented by the police. But unlike JP, Mark’s residence was visited by cops wearing proper uniforms.

In his latest tweet, Soriano said Interior chief Benhur Abalos called him and assured him that he would probe the incident. The interior agency oversees the national police and all police units in the country.

Estomo, in his Saturday statement, apologized for the incident and said a probe will follow.

“The said police officer was already identified and summoned. An investigation will be carried out by the Chief of Police of Marikina City pertaining to this incident,” the NCRPO director said.

The NCRPO director added that he ordered police commanders “to stop and refrain from doing the same,” referring to the incident involving Soriano and a cop.

Violation of privacy

In a statement, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) said the surprise visits being done by the police are a violation of journalists’ right to privacy. They add these incidents trigger the anxiety of media workers.

“Assuming good faith, these meetings and dialogues are best done through newsrooms or through the various press corps, press clubs, and journalists’ organizations in the capital. Far from making us feel safe, the visits add to our anxiety as these were done without coordination from newsrooms,” the NUJP said.

Danilo Arao, journalism professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman, said the PNP’s program is a form of harassment and intimidation against journalists. Both the NUJP and Arao suggested that protection of journalists should be addressed in proper channels and with proper coordination with news media organizations.

Protecting media workers should also not be in the form of increasing police presence because they can be used to justify police surveillance, Arao noted.

“Such actions can be used to justify the surveillance the police are conducting on critical journalists, especially those belonging to the mostly red-tagged alternative media,” the journalism professor said. “To be frank about it, we cannot ask for help from the PNP when it is an enabler of culture of impunity. Therein lies the systemic problem that affects the very lives of journalists and the very practice of journalism.”

Instead of police presence, there are other ways to protect journalists, according to Arao.

“First, the government and PNP should stop red-tagging as it affects not just activists but also journalists and media workers. Second, repressive laws like the anti-terror law of 2020 and the cybercrime prevention act of 2012 should be repealed.”

Arao added: “Third, those responsible for the media killings then and now should be brought to justice, especially the mastermind.”

In the press freedom index of the Reporters Without Borders (Reporters sans frontières or RSF) for 2022, the Philippines ranks 147th out of 180 countries. The ranking measures the state of press freedom in each country – and this means the Philippines is one of the worst countries for journalists. (READ: IN NUMBERS: Filipino journalists killed since 1986)

The interventions made by the government, like the establishment of the Presidential Task Force on Media Security (PTFOMS), did not stop violence against journalists. According to the RSF, the PTFOMS “has proved unable to stem the vicious cycle of violence against journalists.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.