SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Political experts and observers raised their eyebrows when Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte vowed to focus on his anti-corruption drive for the last two years of his term.

It’s not the first time he’s made such a promise. In fact, he makes it in almost every speech, using different words and anecdotes.

But Duterte’s speech on Tuesday, October 27, took it up a notch when he announced the creation of a new task force to investigate corruption in all offices of government, including lawmakers and local government chiefs like mayors and governors.

This is a gargantuan task, given the sheer number of departments, bureaus, and agencies, military and police personnel, hundreds of lawmakers, and more than 1,700 mayors and governors nationwide.

Duterte is giving the justice department, lead agency of the “mega task force,” until June 30, 2022, to finish the job. That’s only one year and 8 months away.

Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra, now in charge of this tall order, told Rappler that Duterte didn’t discuss this plan with him before announcing it.

The details of Duterte’s order raise doubts about its feasibility. What can such a task force really accomplish in such short a time, especially when Duterte’s first 4 years as president were not enough to quash corruption, as the Chief Executive himself admitted?

“I will concentrate the last remaining years of my term fighting corruption kasi hanggang ngayon hindi humihina, lumalakas pa lalo (because, until now, [corruption] has not waned, but intensified),” the President said on Tuesday.

It’s clear Duterte’s televised announcement is important to his messaging strategy. He especially planned to include it in his regular “message to the people,” which is aired or closely watched by virtually all media outlets. Only a few hours later, this message was drilled further during Presidential Spokesman Harry Roque’s press briefing, which also gets significant airtime, where he gave more details about the task force and answered media questions about it.

In recent years, Duterte’s fondness for creating “task forces” to address corruption or other problems has become apparent. It was a task force that probed Philippine Health Insurance Corp (PhilHealth) anomalies. It was a task force that implemented the closure of Boracay Island for cleaning and sewerage improvement projects.

It seems only a new task force can accomplish what another body created by Duterte in 2017, the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission, couldn’t do. The PACC, composed of lawyers supportive of Duterte’s presidential bid, was supposed to do lifestyle checks and investigate presidential appointees suspected of wrongdoing.

The infeasibility of Duterte’s latest order and the high-profile yet formulaic way it’s been communicated to the public leaves Joy Aceron, public policy expert and convenor of corruption watchdog G-Watch, to make one conclusion: “There hasn’t been any cases of systemic corruption that has been resolved, making task forces more like a show.”

Duterte’s track record as a crusader against corruption is lackluster, says Aceron, based on how he and his administration have handled the biggest corruption scandals during his presidency.

“His rhetoric keeps anti-corruption high profile, but it’s all just words and tricks. His approach is reactive, which can be construed as being responsive and decisive to corruption controversies. But looking at the big picture, his response is just for show. Follow-throughs are either non-existent or contradicting,” she said.

Similarly, Lica Porcile and Norman Eisen, writing for public policy organization Brookings Institution, likened Duterte’s anti-corruption rhetoric to his fellow populist leaders Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil) and Donald Trump (United States).

All 3, they said, reject “institutional mechanisms” to fight corruption and prefer to fight corruption “as individuals or through close allies.”

Duterte, who promised to punish even his close friends and allies, “equates governmental probity with personal probity,” they said.

“His promise implied not only that he would not tolerate corruption, but also suggested that his personal oversight was the only oversight needed,” wrote the two in their October 28 article, “The populist paradox.”

Despite Duterte’s rhetoric, his government continues to be “mired in scandal” and characterized by “institutional backsliding.”

“Duterte, Bolsonaro, and Trump have sought to consolidate their personal power at the expense of existing institutions, and this has had severe negative impacts on the justice system, hindering anti-corruption efforts,” wrote Porcile and Eisen.

Pattern in Duterte’s approach to corruption scandals

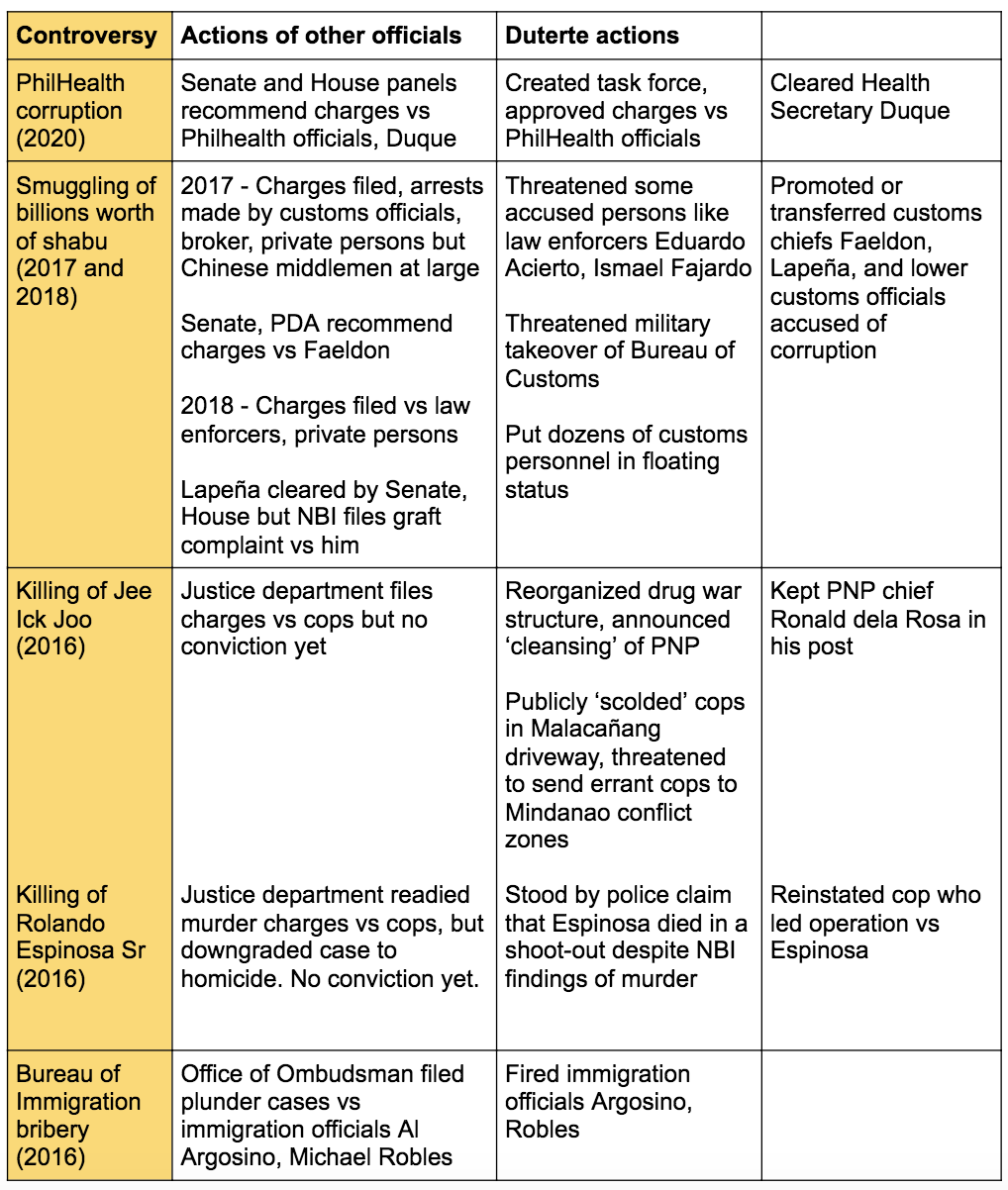

To show a sample, we look back at 4 of the biggest corruption controversies during Duterte’s presidency: PhilHealth anomalies, billions worth of shabu smuggled in 2017 and 2018, the killing of Jee Ick-Joo and Rolando Espinosa Sr by cops, and the immigration bureau bribery scandal in 2016.

There’s a pattern to how these controversies arose and how Duterte responded:

- They blew up independently of any investigation by Duterte, with more shocking details revealed in congressional hearings. Duterte’s most high-profile actions were reactions to media headlines and investigation findings. Many of his actions had a distinct dramatic flair – like summoning “scalawag” police to Malacañang’s driveway for a televised “scolding,” threatening a military takeover of the Bureau of Customs, or claiming he slapped a corrupt budget department official.

- Duterte has stood by some of the implicated officials, like Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, former customs chiefs Nicanor Faeldon and Isidro Lapeña, former police chief Ronald dela Rosa, some lower-level police officers, and customs officials.

- He parted ways with others, agreeing to charges against PhilHealth CEO Ricardo Morales, firing disgraced immigration officials Al Argosino and Michael Robles, and making threats against law enforcers Eduardo Acierto and Ismael Fajardo. Save for Morales, these are lower-level officials who have minimal close personal ties with him.

Here’s a comparison of the 4 scandals, in terms of how Duterte and other officials sought to resolve them:

More detailed summaries of the scandals and what became of them can be found at the end of this article.

These controversies show that Duterte has been largely reactive and inconsistent in holding officials accountable for anomalies. In the PhilHealth, shabu smuggling, and Espinosa scandals, he even vouched for the integrity of officials (Duque, Faeldon, Espinosa, Marvin Marcos) before investigations ended. Critics pointed out that a vote of confidence from no less than the Chief Executive could influence investigators and color their findings in favor of the accused.

If that’s not worrisome enough, Duterte has done other things that poke more holes into his anti-corruption stance.

A majority of officials he claimed to have fired for corruption still aren’t facing any charges.

He has kept officials tainted by more than a “whiff” of corruption in his government, though in different positions. (READ: Duterte transfers customs officials accused of corruption to DOTr)

He has kept his last two Statements of Assets, Liabilities, and Networth from the public, the first president to do so in 30 years. The SALN shows how much wealth a public official has accumulated for the year that has passed. Harry Roque, tired of SALN questions from the media, finally said on Thursday that he would “ask” Duterte about plans to publicize his SALNs.

Duterte has skirted around allegations that he himself has hidden wealth. Instead of proving the claims false outright, he has threatened the Anti-Money Laundering Council and fired officials in charge of the investigations.

He’s threatened and undermined independent constitutional bodies like the Commission on Audit and the Commission on Human Rights. The COA scrutinizes how the government spends public funds, while the CHR investigates human rights abuses by state forces like the police and military.

Duterte’s biggest contributions to fighting corruption may be his efforts to increase the take-home pay of police and soldiers, signing orders and legislation to reduce red tape, and his near-constant railings about government agencies sitting on permits.

His spokesman, Roque, says the strategy of making corruption task forces may at last be the winning solution to persistent malfeasance.

But glaring inconsistencies in the President’s own actions could undermine his promised crackdown in the months he has left to make it count.

Summary of top corruption scandals:

PhilHealth anomalies

Of the allegations of widespread corruption in PhilHealth, what stood out was the questionable emergency cash advances to hospitals and a supposedly exorbitantly priced IT system. Amid congressional hearings, Duterte asked PhilHealth CEO Ricardo Morales to resign. He then created a task force to probe the accusations and file cases against officials suspected of involvement. The task force eventually filed a criminal complaint against Morales and other PhilHealth executives before the Office of the Ombudsman. The complaint spared Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, though lawmakers recommended he face charges too because he chairs the PhilHealth board. Duterte continues to defend Duque.

P6.4 billion and P11 billion shabu smuggling scandals

In 2017 and 2018, customs officials were grilled in congressional hearings on how billions worth of shabu from China were able to enter the Philippines, despite Duterte’s hardline stance against drugs.

In the 2017 controversy, only the Filipinos charged over the importation were arrested. The Chinese middlemen are still free. Nicanor Faeldon, head of the Bureau of Customs back then, was taken out of his post but given another position by Duterte. Earlier, the justice department, run by Duterte’s alter ego Vitaliano Aguirre II, had cleared Faeldon despite the Senate and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) saying Faeldon should be held accountable. Duterte also recycled two customs officials accused of collaborating with the drug smugglers. Milo Maestrecampo and Gerardo Gambala were given positions in the transportation department.

For the 2018 case, most of the private individuals and customs officials have been charged and arrested. But Eduardo Acierto, one of the accused and a retired police anti-drug official, is on the run with a hefty P10-million price on his head offered by Duterte. Shocking the law enforcement community further, the PDEA’s second in command at the time, Ismael Fajardo, was implicated in the smuggling. Fajardo is also missing. Lapeña, the customs chief at the time, was promoted to a Cabinet post. Unlike Faeldon, Lapeña was cleared by both the Senate and House panels. The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), however, filed a graft complaint against Lapeña. He continues to hold the post of Technical Education and Skills Development Authority chief. Meanwhile, Duterte also promoted Vener Baquiran, a district collector being investigated over the shabu shipment, to customs deputy commissioner.

To address customs corruption in general, Duterte summoned a large group of its officials and personnel to Malacañang to warn them of administrative charges if they don’t resign. He placed them on “floating status” and asked them to report to his office while they are under investigation.

Killings of Jee Ick-Joo, Rolando Espinosa Sr

The murder of Korean businessman Jee Ick-Joo by police was so scandalous that Duterte called a temporary halt to his famous campaign against illegal drugs. He gave a sudden press conference where he announced a “cleansing” of police personnel and reorganization of the drug war where it would be led by the PDEA and not the embattled police. He then called some 200 “scalawag” cops to the driveway of Malacañang, where he berated them on live television. Police officials later on admitted many of the cops present were guilty of only minor violations like being late or not reporting for duty. Then-national police chief Ronald dela Rosa stayed in his post until his retirement from the force. The government has identified and sued suspects, most of whom are police officials, but none have been convicted. The killing of Jee Ick Joo led to the abolition of the PNP Anti-Illegal Drugs Group, but when the controversy subsided two months later, the unit was reincarnated as the Drug Enforcement Group.

The killing of a Leyte town mayor while in jail became more scandalous when the NBI concluded that it was murder and not death in a shootout, as claimed by the cops involved. The mayor, Rolando Espinosa Sr, was linked to the drug trade. But unlike with the Jee Ick-Joo case, Duterte did not punish the police. Instead, he even sided with them and ordered the reinstatement of the cop, Marvin Marcos, who supervised the operation. The town’s police chief, Jovie Espenido, received praise and accolades from Duterte. Espenido was the same cop who masterminded a police operation that led to the death of another mayor suspected of drug links, Reynaldo Parojinog of Ozamiz City. After getting promoted to head Bacolod City police’s drug enforcement team, he was relieved after his inclusion in a preliminary drug list.

Bureau of Immigration bribery

The earliest scandal to taint the Duterte administration, it involved Bureuau of Immigration officials allegedly asking Chinese businessmen for a bribe for the release of their workers arrested for illegally staying in the Philippines. BI officials Al Argosino and Michael Robles, Duterte’s appointees and fratmates, were eventually charged with plunder.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[PODCAST] Duterte’s secretive Malacañang](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/09/seat-of-power-podcast-09052020.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] What kind of citizens are we?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-what-kind-of-citizen-are-we.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=333px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.