SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Against the royal blue and rich red of the Philippine flag, President Rodrigo Duterte stood behind a podium bearing the presidential seal, eyes focused on the camera as its lens zoomed in slowly, closing in for a tighter shot.

Frustrated over the events that took place on April 1 in Quezon City, a sudden announcement was given at past 9:30 pm, that the Chief Executive was to give a speech. Less than 10 minutes after the notice was sent to media, Duterte appeared on Filipinos’ screens to deliver a stern warning.

A furious Duterte said he would not hesitate to take action following the arrest of 21 Quezon City residents who were apprehended for demanding government help and protesting without a permit.

The protest, which Duterte accused lefitst group Kadamay of instigating, had manifested weeks of mounting desperation spurred by the government’s slow response to aid residents who were left hungry and out of work due to the lockdown in Luzon.

Lashing out at the Left, the President warned they would be detained.

Then he took it a notch up.

“I will not hesitate. My orders are sa pulis, pati military, pati mga barangay na pagka ginulo at nagkaroon ng okasyon na lumaban at ang buhay ninyo ay nalagay sa alanganin, shoot them dead,” he said. “Naintindihan ninyo? Patay. Eh kaysa mag-gulo kayo diyan, eh ‘di ilibing ko na kayo,” Duterte said.

(I will not hesitate. My orders are to the police and military, also the barangay, that if there is trouble or the situation arises that people fight and your lives are on the line, shoot them dead. Do you understand? Dead. Instead of causing trouble, I’ll send you to the grave.)

Outrage over Duterte’s remarks was swift. Social media timelines flooded with users who were shocked and angered over the President’s remarks, calling for his ouster.

By his next address two days later on April 3, Duterte claimed he hadn’t issued a “shoot to kill” order.

“I never said in public shoot to kill, period. Sinabi ko…if you think that your life is in danger, maging biyuda ang asawa mo na maganda, mag-asawa uli, at ang mga anak mo mawalaan ng tatay, ‘pag tiningnan mo na delikado ang buhay mo, patay, unahan mo na, patayin mo,” he said.

(I never said shoot to kill, period. I said…if you think that your life is in danger, your beautiful wife will become a widow, marry again, and your children will become fatherless, if you think your life is at stake, kill, go ahead, kill them.)

He then directly addressed the calls for his ouster. “Bakit pa ako magpayag na magbarilan tayo? Kaya ganun. Huwag na ‘yang ‘Oust Duterte’ na mga fake news,” he said. (Why would I allow us to shoot one another? So there. Never mind that ‘Oust Duterte’ that’s fake news.)

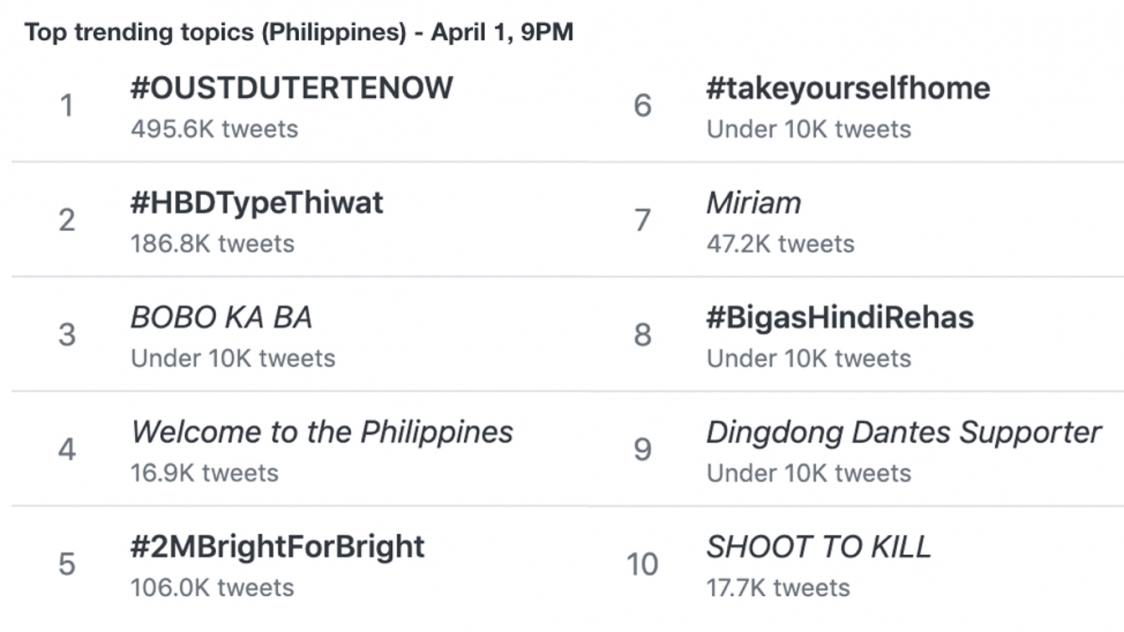

But by then, widespread online protest had already taken place. Outrage over Duterte’s remarks were widespread with #OustDuterteNow trending worldwide with almost 500,000 tweets.

To see how the public responded to the President’s speeches online, Rappler’s data team collected a sample of 15,000 tweets with mentions of Duterte and related words from March 30 to April 2, 2020, and clustered these according to topic using natural language processing.

Compounded with analysis from US-based Graphika that dove into the specific hashtags that trended, the data shows that these critical movements were not only large but organic – flooding out even the administration’s supporters known for their coordinated campaigns to mob critics and whitewash the government’s lapses on social media.

Seeds of discontent

While critical tweets against Duterte and his administration peaked on April 1, frustrations were already boiling from March 30, when he addressed the nation to give updates on the government’s COVID-19 response.

It was the first Monday after Duterte signed a law granting himself special powers to contain the spread of the virus. Filipinos were told to expect a message from the President tentatively set at 4 pm.

Filipinos waited for an hour, and then another, and then 5 more. It was past 11 pm when Duterte’s message went live on their screens.

“May mga doktor na, mga nurses, attendants, namatay. Sila ‘yung nasawi ang buhay para lang makatulong sa kapwa. Napakasuwerte nila. Namatay sila para sa bayan,” Duterte said early into his pre-recorded address.

(There are doctors, nurses, attendants who died. They were the ones who died helping others. They are so lucky. They died for the country.)

The statement, intended to praise health workers who have risked their lives, quickly drew backlash both online and in the front lines of the outbreak. Doctors, nurses, and health workers did not need the sort of “praise” from the President, Mikey*, a doctor at a coronavirus designated hospital told Rappler.

“I’m doing this because it is my duty, but I did not sign up to die,” she said. “I don’t want to die.”

Online, Duterte’s remarks drew fierce criticism with many users pointing out doctors died due to inadequate protection and the government’s failure to provide life-saving protective equipment early on in the outbreak.

Like other speeches, the President’s remarks targeted critics and focused on threats, instead of facts and concrete plans on the outbreak. Filipinos once again took to social media to express their anger at the government’s handling of the crisis.

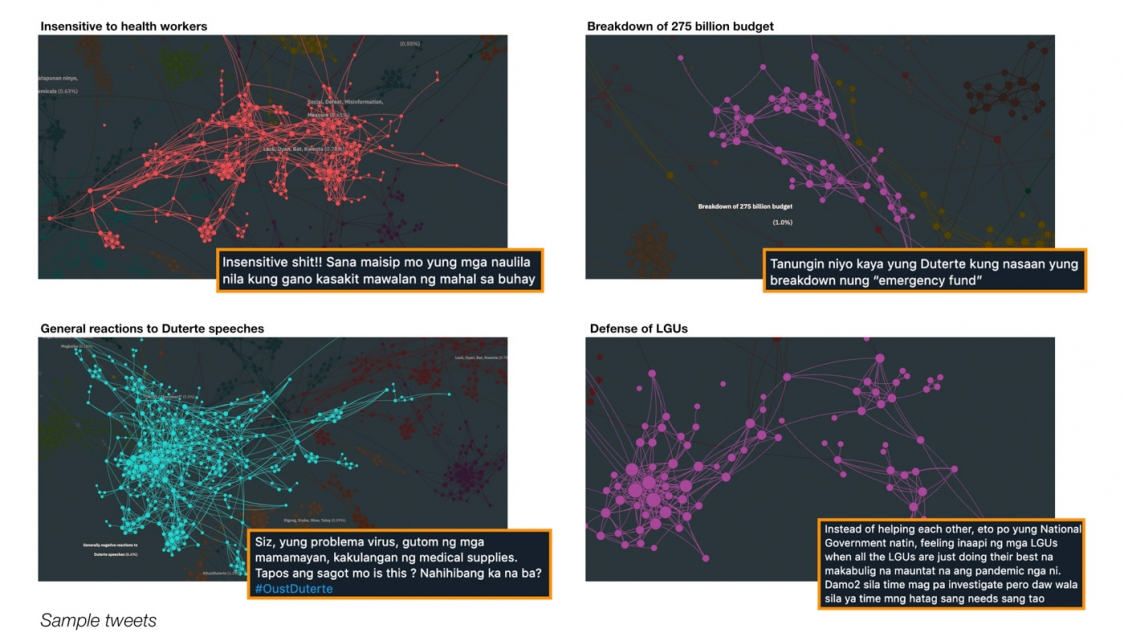

Rappler found that the two speeches on March 30 and April 1 made for the core of online conversations on Duterte. Tweets were largely critical of the Duterte administration, with the one of the largest clusters hitting the President’s remarks on how health workers are “lucky to die” for the country.

Filipino Twitter called the President out, saying he “should not romanticize their deaths” and that the remarks were “insensitive” to medical workers who risked their lives.

On the sidelines are criticisms on other fronts.

As early as 6 pm on March 30, #DuterteStandardTime trended on Philippine Twitter as people waited for the Duterte speech broadcast 7 hours late. Online users criticized his tardiness at such a crucial time, calling it a trend for the President.

“As both head of state and head of government, the President is expected to not only provide direction and lead government but also provide a sense of unity among citizens, particularly during periods of crisis,” University of the Philippines Political Science professor Ela Atienza said.

She added, “Unfortunately, President Duterte’s statements, timing of public statements, and style of delivery have not provided reassurance and trust in government.”

Public sentiment manifested this as others online also criticized the lack of concrete plans in his speeches. With Filipinos halfway into the lockdown first set to end on April 12, the public demanded clearer directions from the government on what to do and expect. (Duterte later extended the lockdown until April 30 and then again to May 15 for certain areas, including Metro Manila.)

Conversations were also dedicated to calls for greater transparency on the breakdown for the P275-billion response fund related to the Bayanihan law.

Aside from these topics, the bulk of the 15,000 tweets sampled that centered on Duterte consisted of general reactions to his speech and mostly of people cursing the President and the government, accusing the administration of being “incompetent.”

Outrage peaks

The day’s events on March 30 catalyzed reactions on social media. By April 1, public outrage against Duterte and his administration peaked after he ordered cops and soldiers to “shoot dead” people who broke quarantine protocols.

The timing of it could not have been worse.

Duterte’s words, delivered during an impromptu televised message on April 1, came hours after the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) summoned the popular Pasig City Mayor Vico Sotto for a possible violation of the Bayanihan Act, the law which granted Duterte special powers.

The NBI did not disclose which specific Pasig policy was under investigation. Sotto had earlier appealed to Malacañang if he could allow tricycles to operate in his city to ferry frontliners and people with emergencies – a pitch that several executive officials rejected.

The incident followed with Duterte scolding local government units, warning them to “stand down” and abide by orders issued by his office and the government’s coronavirus task force. While the President made no direct mention of Sotto, conversations had related the two incidents to one another.

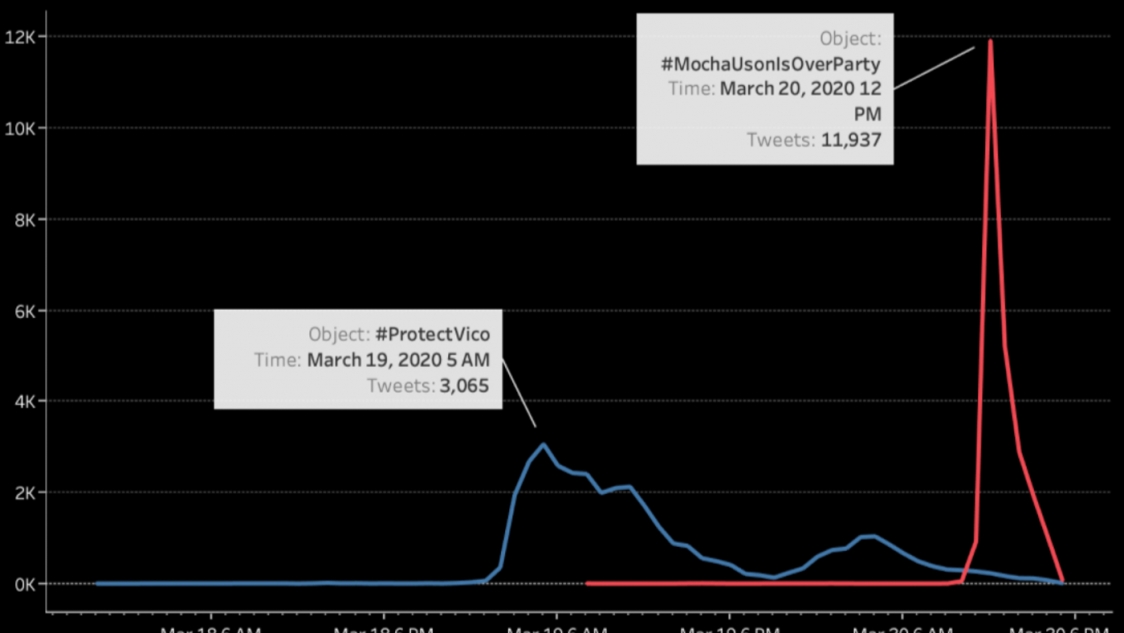

This triggered widespread protests online, with #ProtectVico trending on Twitter (the second time the hashtag trended within two weeks), condemning the government for politicizing response to the crisis.

By the time Duterte delivered his April 1 speech, public sentiment against him pushed to a tipping point: #OustDuterteNow trended worldwide on Twitter at 9 pm – the same hour his speech took place – generating almost 500,000 tweets.

Organic groundswell of anger

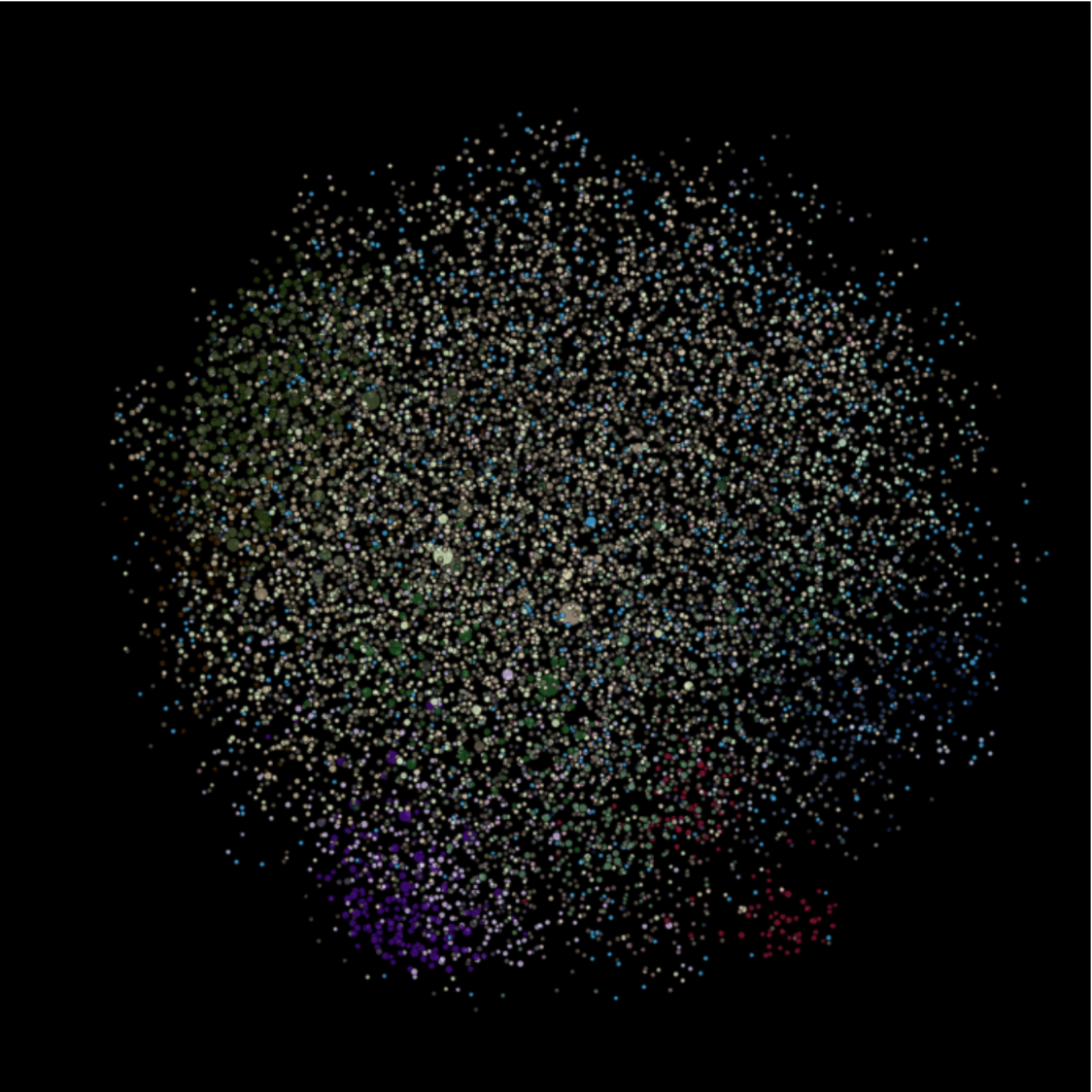

Analysis by Graphika showed that #OustDuterteNow was a largely organic movement, with little signs of manipulation.

Their mapping of the hashtag below shows a wide range of interest groups engaging with the hashtag, with the majority of these segments being largely non-political and clustered instead on entertainment and cultural topics.

Among accounts that engaged in discussion critical of Duterte were users from various interest groups like Philippine K-pop, celebrity fan groups, LGBT groups, western pop celebrities, and Philippine culture, celebrities, music. Others that participated were from the Philippine opposition and activists.

This suggested a wider online dissatisfaction with Duterte beyond the usual online activists.

Atienza said widespread public frustration seen on social media may be because unlike other issues that have hounded Duterte’s administration – such as the drug war or his preference for warmer ties with China – the coronavirus outbreak affects each Filipino.

“The pandemic affects everyone, or at least threatens everyone, not just a sector of the population. The threat of the pandemic is so real that there is a feeling of urgency and greater demand for government to act fast and be accountable,” Atienza said.

Yet despite this, according to Atienza, Duterte and other government officials have been unable to foster a sense of unity.

In response, Filipinos who have increasingly turned to social media during the lockdown took to speaking out against Duterte and his administration.

The rather sparse and more loosely connected map (shown below) reflects the traction of #OustDuterte among users grouped by interest on Twitter. The majority of the map showed conversations consisted largely of entertainment and cultural interest segments that lack the density typically observed in politically coordinated accounts.

This was evidence that politically focused groups did not appear to be the main organizing force behind the campaign.

Ateneo School of Government Dean Ronald Mendoza said public frustration seen in online discussions reflected how the government’s weaknesses were made more obvious during the coronavirus crisis.

“Crises test the government’s ability to facilitate collective action (even across its own line agencies) typically exposing the lingering need to boost whole-of-government response capabilities,” Mendoza said.

He added, “The government’s seeming insensitivity to the realities of ordinary working citizens who were quarantined, combined with delayed plans to provide income support… all may have also exacerbated the sense that government was insensitive and disconnected from reality.”

The sense of frustration and Filipinos’ apprehension over uncertainty brought by the pandemic drowned out any response that attempted to express support for the government’s response.

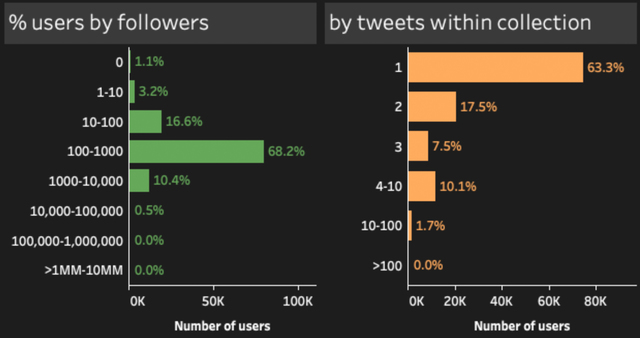

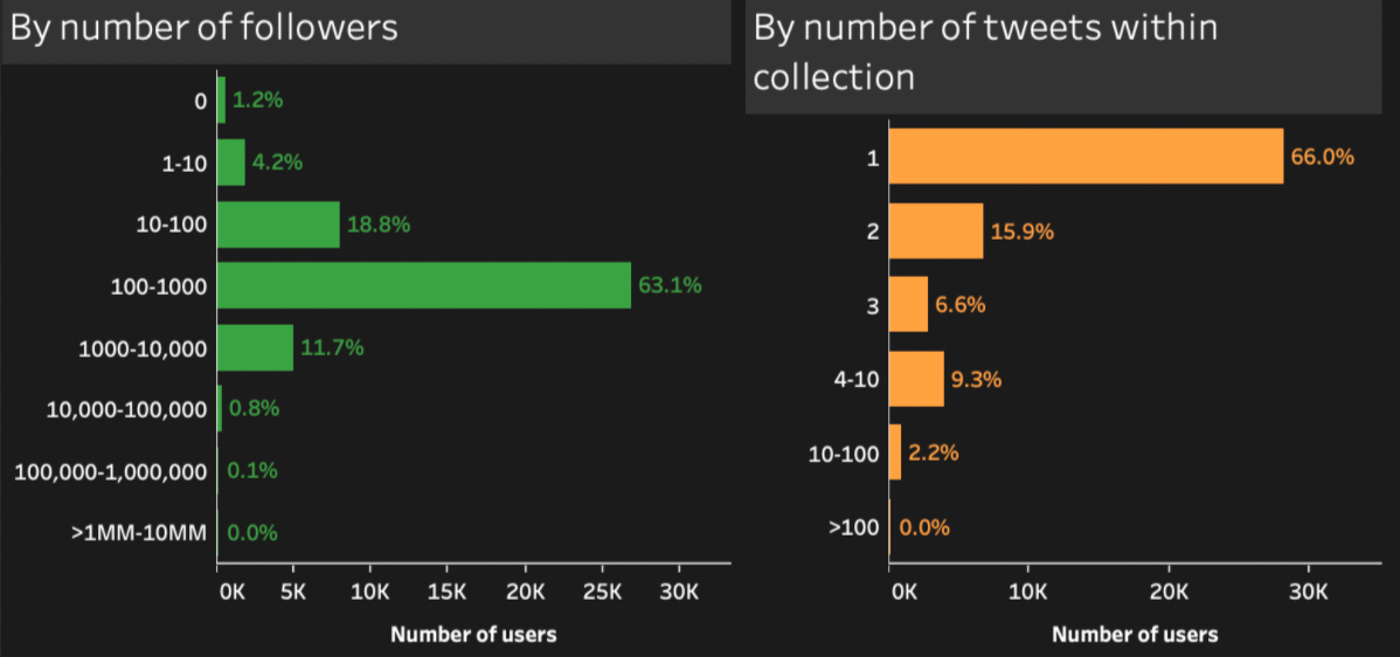

Meanwhile, Graphika’s analysis also showed that about 80% of the accounts that participated in discussion critical of Duterte have more than 100 followers and over 60% of these accounts produced just one tweet using #OustDuterte.

The most shared tweets using #OustDuterte also did not originate from influential or celebrity accounts but were posts from seemingly normal users that went viral.

About 80% of the accounts that used the hashtag have more than 100 followers and over 60% of accounts produced just one tweet using #OustDuterte.

Data showed the #OustDuterteNow trend was largely organic and participatory with little signs of manipulation or coordination. This pointed to a groundswell of negative public sentiments against the President’s handling of the crisis, with users who typically did not discuss politics joining in on these conversations.

Overpowered propaganda

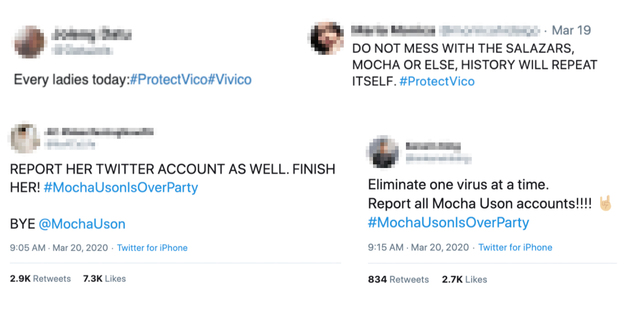

Signs that propaganda tactics were failing were seen in mid-March when discontent online began to stir. Duterte’s supporters tried several times to resort to old efforts of drowning conversations with praises of the President and mobbing perceived enemies on social media.

But these were shut down by angry Filipinos.

In fact, at the peak of the online outrage against Duterte, #IStandWithThePresident also trended online, generating more than 130,000 tweets at its height (including tweets that mocked the hashtag). This, however, was largely drowned out by #OustDuterteNow.

Another attempt to push out messages against those critical of the administration also contributed to the build up of public frustration by April.

On March 18, administration officials and supporters blasted Sotto for allowing tricycle drivers to operate while Luzon was on lockdown. This included blogger-propagandist Mocha Uson who called Sotto “pabebe” (childish) on her Facebook page. Uson’s page has a following of some 5 million users.

This was in keeping with the type of systematic and sustained response seen in the past 3 years against journalists and critics of the President: officials around Duterte hit perceived critics on the ground, while online supporters pounded them en masse.

This time around, however, this attempt was not met with the usual silence. #ProtectVico quickly trended online, generating over 37,000 tweets from almost 22,900 users. It then snowballed into an online campaign targeting Mocha Uson, with users encouraging everyone to report her blog on Facebook in an attempt to close it down.

On March 20, her Facebook page became unavailable. People speculated that she might have deactivated the page herself.

In celebration, #MochaUsonIsOverParty trended on Twitter, with 24,000 tweets from over 11,800 distinct accounts. Campaigners then started targeting other blogs notorious for spreading pro-Duterte propaganda, such as Crabbler, Mark Lopez, and Mr Riyoh.

Like #OustDuterteNow, the data suggests that #ProtectVico and #MochaUsonIsOverParty was largely organic with little signs of manipulation. Over 80% of the accounts have between 100-1,000 followers and over 65% of accounts produced just one tweet using either (or possibly both) combination of hashtags.

This laid the groundwork for widespread dissatisfaction seen online on April 1.

The most retweeted tweets to feature either hashtag were in support of Sotto’s actions to control the COVID-19 outbreak or were used to counter criticism from blogger Mocha Uson.

Some users went as far as requesting social media administrators to suspend her accounts. These posts were popular across all groups including both the culture and entertainment segments critical of Duterte – the same ones that participated in the bulk of conversations on April 1.

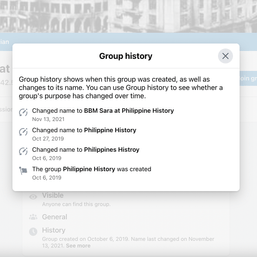

Later on April 10, Twitter “hundreds of accounts” tweeting under specific hashtags meant to defend the Philippine government response to the coronavirus pandemic.

An email from Twitter to The Washington Post, said the accounts in question violated Twitter’s policies against platform manipulation and spamming. This includes posting duplicate content across multiple accounts, making duplicate or multiple accounts, and sending a large number of unsolicited replies or mentions.

The Washington Post report noted that hashtags in support of Duterte followed after public outcry over government actions against the poor during the coronavirus quarantine. These hashtags included #IStandWithThePresident and #YesToABSCBNShutdown.

The mass takedown by Twitter was part of a wider effort of other social media platforms to get rid of accounts that spread disinformation during the pandemic. It’s also the first announced case of Twitter actually taking down a network connected to the propaganda machine.

When it came to the Duterte administration’s handling of the outbreak – genuine online users drowned out propaganda tactics.

Duterte’s test

As the coronavirus pandemic rages, political analysts say the outbreak may be Duterte’s biggest test yet. Now more than ever, Filipinos are demanding transparency and accountability in government’s response.

The stakes are high as missteps in government’s response could mean the loss of lives due to the disease.

For Mendoza, the crisis carries a high political cost for Duterte as the outbreak hits several of his main constituencies in both the middle class and overseas Filipino workers.

“If government is unable to respond effectively to mitigate the crisis impact, then we may witness change in political support,” he said.

According to Atienza, Duterte and his team may have touted the war on drugs, massive infrastructure programs, and development in regions outside Metro Manila as legacies of his administration, but what is clear is the pandemic “has changed the agenda for the rest of his term.”

“President Duterte’s leadership style appears not fit for this crisis. This is a different kind of crisis that requires reliance on experts and stakeholders as well as making sure people are involved and not left behind,” she added.

“Whether he likes it or not, he will now be judged based on what he and his administration had done and did not do during the pandemic,” Atienza said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.