SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

VIENTIANE, Laos – The news media in this country is severely restricted, from who is allowed to own it to what it’s allowed to publish. But the growth of social media platforms has led to the proliferation of self-declared news outlets and self-proclaimed journalists who challenge government narratives and inform the public – yet also produce unverified and exaggerated reports.

Only members of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, the only political party in Laos, are allowed to oversee any public media content. According to Lao Media Law, all forms of Lao media must align with party directives, state laws, and socio-economic development plans. State bureaucrats are mandated to counter rumors and reports they deem are harmful to the government and its officials.

However, in the past several years, Laotians have gained access to various social media platforms, sparking a surge in citizen journalism throughout the nation, alongside a modestly increased acceptance of privately-owned media outlets affiliated with family members of party officials.

The tipping point happened in the aftermath of the July 2018 Xe Pien-Xe NamNoy dam collapse in Attapeu Province, southern Laos, which was a massive environmental and human-made disaster that left hundreds missing and at least 6,000 people homeless.

State-controlled media’s vague reporting during that crisis prompted social media users to share bits and pieces of news that they had gathered elsewhere, according to media watchdog Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFEnet). Following the dam’s collapse, the government initially provided limited information, but gave no official response to questions about the impact on affected families or the allocation of funds.

While Kaosan Pathet Lao, the state’s official news agency, said an investigation was underway, subsequent reports from the government were scarce. The news agency attributed the collapse to “substandard dam construction,” with no further updates.

In the days that followed, unofficial sources, including private Facebook profiles, started to divulge crucial information about the inner workings of the infrastructure project, including its Chinese origins. This news swiftly spread across the region, prompting international media coverage of the disaster. However, it wasn’t until six years later that significant corruption allegations surfaced.

On July 21, 2023, Radio Free Asia (RFA), a prominent human rights online publication, reported that up to US$4.2 million allocated for dam survivors had gone missing. That same year, Lao authorities said that the construction of housing for victims of the 2018 dam disaster was already 99% complete. However, a survivor told RFA that most families had relocated to resettlement villages where they were provided parcels of land that were too small for growing rice and vegetables.

“We were living in a camp that was very crowded,” one survivor told RFA. “We didn’t even have water in our bathrooms. The camp authorities said that they didn’t have money to install more pumps or to fix the broken pumps,” other survivors told RFA.

Facebook quickly got inundated again with images depicting the flood-ravaged villages in the aftermath of the collapse, prompting cautious discussions among its users about the extensive Chinese investments in hydropower projects.

Breaking state barriers

Facebook has cemented itself as one of the world’s most influential social platforms, with over two billion active users daily as of April 2023. This global influence is mirrored in Laos, where it serves as a primary platform for information dissemination. Compared to traditional media websites, Facebook posts by Lao media outlets garner broader reach and higher engagement, highlighting the platform’s dominance in the media environment across Laos.

Laopost, one of the very few privately-owned Lao language media outlets that publishes both on its website and social media, including Facebook and TikTok, demonstrates this dominance with statistics. In January 2024 alone, Laopost Facebook reached over 7 million devices, while the website reached only 31,000 users, data showed.

Meanwhile, combining 12 of the most popular non-government media pages in Laos that cover news along the lines of tourism numbers in Laos, daily accidents, government reports, and public opinion, results in an average reach on Facebook of 17.6 million in the entire year of 2023.

The proliferation of unregistered news outlets in Laos poses a challenge to understanding the country’s media landscape fully – and also unmasks the weaknesses of state control.

Laos’ regulations prohibit private media ownership, creating a disparity between traditional media and Facebook’s freedom of publication. This gap enables malicious actors to exploit the situation, disseminating information without adhering to Lao government regulations but instead abiding by the policies of Meta Platforms, Facebook’s parent company.

Malicious actors

Disinformation plagues news publications worldwide, and Laos is no exception.

However, what distinguishes news websites in Laos is their non-political nature, especially among unregistered outlets. In Laos, a one-party state with centralized governance, fake news outlets target society, rather than the government, to attract clicks and engagement.

This has facilitated the dissemination of fake news, bypassing government regulations.

The ease of creating these pages fosters a lack of journalistic accountability and professionalism. Operating without scrutiny, individuals pursue monetary and intangible rewards, such as greater reach and engagement. As a result, these fake pages often neglect journalistic ethics without facing consequences.

This was highlighted by an incident in 2021 involving a high school girl who suffered trauma after explicit videos of her were circulated online without her consent. Despite the perpetrator being identified, no legal action was taken against him. The girl requested to remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of the situation.

“The issue started when my then boyfriend and I broke up. He was mad at me, so he [reached out to] some news outlets to share sexually explicit videos of mine without my knowledge,” she said.

The post, which has now been removed, went viral on social media, with people from across the country commenting on it. Some advocated for the deletion of the post, while others pushed for banning her on Facebook, calling her a “prostitute” for sleeping with a boy at her young age and filming it, further claiming she deserved to be shamed on social media.

“It was a horrible time in my life,” she said as she reflected back on that period. “It was difficult for me to leave my room, I couldn’t look my parents in the eyes, I was ashamed to confront my friends, I felt like my life had ended right then and there.”

Although the person behind the initial posting was later revealed to her, no arrests were made nor fines imposed. We reached out to the girl, who is turning 20 this year, to clarify information that her parents did not initiate any complaint. She confirmed that her family did not pursue any case.

While some fake news outlets may not resort to the same tactics of targeting individuals for likes and shares, others have clear agendas and are willing to manipulate narratives, misrepresent facts, or oversimplify stories in their promotion, preview, or summary.

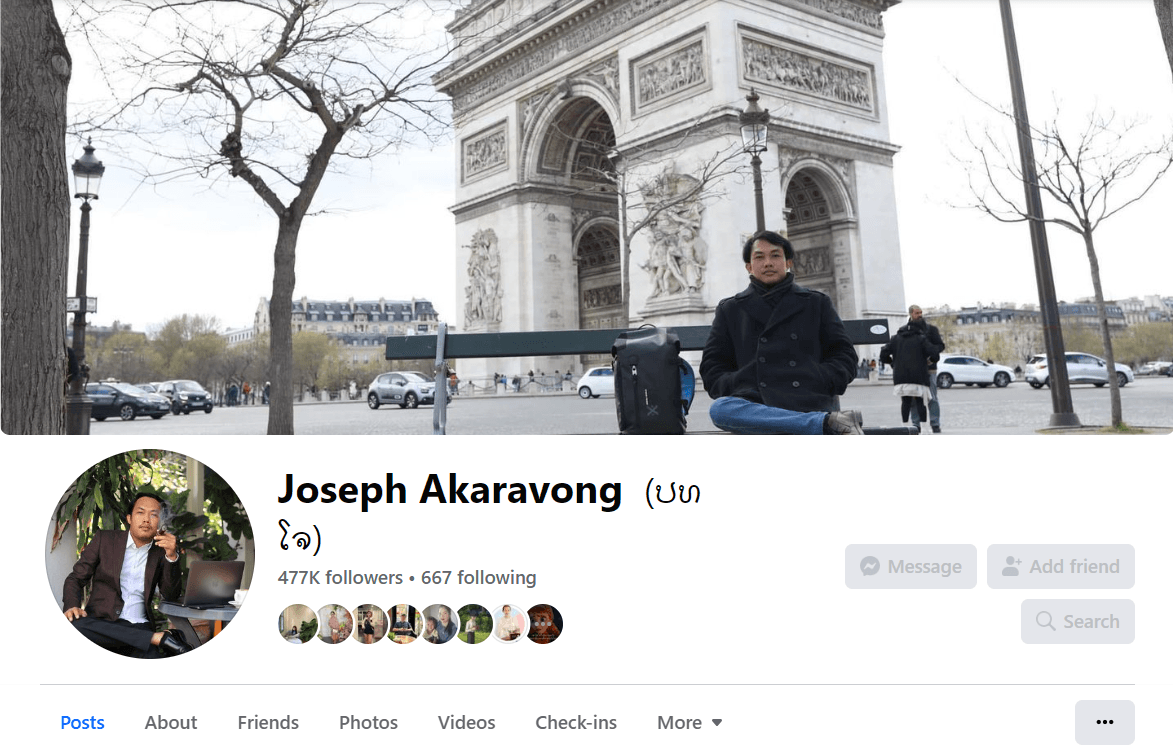

Among them, Joseph Akaravong stands out for the influence he has over the media landscape in Laos.

Joseph Akaravong: Who is he and why is he influential?

Also known online as “President Joseph,” Joseph Akaravong emerged as a political influencer in 2022.

An exiled political activist from Luang Prabang, Joseph gained attention for exposing alleged corruption within Laos’ government, notably implicating former prime minister Phankham Viphavanh in mismanagement and corruption related to the Attapeu dam collapse in 2018.

Fleeing to Thailand and later settling in France as a political refugee, Joseph’s influence expanded further in 2022 when he reported on the murder of Viphaphone Kornsin, a 36-year-old businesswoman from the Saysettha District of Vientiane who was reported missing on September 10 that year.

The victim was initially found in a suitcase floating on the Mekong river and was brought ashore by villagers of Thailand’s Nakhon Phanom province, before the police arrived and discovered the body of a woman inside.

What propelled Joseph’s Facebook page to become one of the most influential in Laos wasn’t just the murder itself, but his revelation that the victim was allegedly a secret spouse of the former Laos prime minister Phankham Viphavanh.

Throughout the two to three months after the murder, Joseph posted texts alleging that the two individuals had a daughter together who was reportedly kidnapped and brought to Singapore. He also showed videos of the former prime minister at a birthday dinner with the victim. Subsequently, the former prime minister resigned from his position, leading many in Laos to embrace Joseph’s ideals, bolstering his influence.

Another incident highlighting Joseph’s influence occurred in May 2023 when Anousa “Jack” Luangsuphom, political activist and admin of anti-government Facebook page Power by Keyboard, was shot while in a cafe with friends. Minutes after the shooting, Joseph claimed that they were friends and that Jack had been killed, a statement that gained international attention, including coverage by the BBC. However, the report was later refuted when Human Rights Watch confirmed that Jack survived the shooting.

The problem is that Joseph’s influence lacks journalistic accountability, evident in his biased coverage against China’s presence in Laos, which has fueled growing anti-Chinese sentiment among the populace.

Fanning hatred toward Chinese

Unregistered media outlets in Laos have propagated hatred toward the Chinese through sensationalized reporting.

An example of this is when these outlets began disseminating reports of Chinese men purchasing Lao girls, particularly in rural areas. A post by Khaosod – ຂ່າວສົດ on February 4 showed a video of Lao girls in rural areas taking turns to stand on scales. However, the innocence of the video was marred by the accompanying caption, which said: “Chinese people buying Lao women is becoming an epidemic. Chinese people are claiming that they will get married and bring them [Lao girls] to the country. The brides cost between 100-300 million kip, depending on the beauty. There are also brokers who are Lao themselves.”

Alan (a pseudonym used to protect the individual) clarified that the video was misconstrued. He, being fluent in Chinese, explained that the girls were simply weighing themselves. However, due to the misleading presentation of the post, viewers inferred that the girls were being sold based on their weight, which was not the case in the context of the video.

Such instigations are common among Lao social media circles. It’s quite common to stumble upon videos featuring young girls or groups of friends engaging in seemingly innocuous activities. However, once these videos go viral, they often get misappropriated by many users.

This frequently leads to unofficial campaigns against Chinese influence in Laos. What is concerning is that those involved are typically Lao youths, who may unknowingly put themselves at risk by simply posting a “fun” video without any ulterior motives.

There’s a popular video of six young Lao girls introducing themselves in Chinese. Although the place where the video was posted is unclear, what is evident is that a Lao facebook page, “We are Lao Lets Love Each Other,” recycled the content to make it seem like they are selling themselves to Chinese individuals.

Comments on the video also reinforce the misconception that was pushed by the admin of the page, stating things such as: “look as those prostitutes,” “Lao girls are all like this,” sarcastically stating “Congratulation” – a term often used to besmirch the Lao government – and even “Lao girls won’t date you anymore, they only go for Chinese money.”

The same page is also known for presenting content reminiscent of a news TV channel. However, it frequently resorts to taking videos out of context and sensationalizing headlines to capture online viewers’ attention.

For instance, on April 1, the page posted a two-hour-long video covering a wide range of topics. Despite this, the headline misleadingly stated that Lao roads were in a dangerous state due to the Lao government allowing Chinese companies to spread chemicals on Lao land. This was accompanied by footage of an unrelated accident. Additionally, the page included a video of Chinese roads at the 1:30 mark, while a Lao government official was speaking on the development of the country, further muddying the context of the content.

But these are not isolated occurrences. Negative actions attributed to Chinese individuals are widely circulated on social media and amplified by unregistered outlets. Posts and captions on platforms like Facebook often harbor language that fosters animosity and hostility toward Chinese people, a sentiment reinforced by supportive comments of hate toward them.

Ironically, the governments of Laos and China enjoy good relations. Could these incidents reflect a degree of unhappiness over how Chinese projects in the country have been implemented?

Laos and China first established diplomatic relations on April 25, 1961. In 2017, the two countries agreed to further strengthen ties. “Laos and China have always maintained a very friendly cooperative relationship,” Laos’ Prime Minister Sonexay Siphandone said during an interview with CGTN, a Chinese state-run English news channel.

Over the years, the two countries ramped up their diplomatic and economic relations, cemented by the establishment of the Laos-China Railway in 2021. In 2023, Chinese companies tripled investments from the previous year, investing in 17 projects worth $986 million in Laos. The increased investment has positioned China to soon become Laos’ top trading partner, replacing neighboring Thailand, according to the Lao Ministry of Planning and Investment.

What’s being done?

Efforts to combat disinformation in Laos have fallen short due to challenges in reaching the predominantly rural population and the late adoption of social media.

The Lao government has initiated measures to address the issue, including establishing a special task force under the Ministry of Public Security and ordering the registration of official social media platforms. However, these efforts have had minimal impact on the social media landscape.

On May 20, 2021, the Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism ordered the departments of Information, Culture and Tourism in all provinces to keep records of official social media platforms, including websites, online news pages, and Facebook pages, and to forward them to the mass media department.

Such initiatives have had little to no effect on the social media landscape in the country. As reported in October 2020, 20 Facebook pages, including Tholakhong, Inside Laos, and Lao Youth Radio, had been registered, while others such as Aunt Next Door and Power by Keyboard, which had been created since then had yet to comply with the order.

As Facebook becomes more integrated into daily life, understanding the impact of fake news on media outlets, especially in countries like Laos, is crucial.

To this end, the Ministry of Education and Sports created a national curriculum for information and communication technology education from the primary through secondary levels to cover themes such as computer basics, internet safety, online communication, digital citizenship, and coding.

Additionally, more campaigns to improve digital literacy programs are still awaiting additional support from government authorities. These programs include the initiative of Pathana Hoymoune, a Lao ASEAN Youth Advisory Group (YAG) member, who started Diginovator. The Diginovator campaign aims to equip young people with essential digital literacy skills, enabling them to become responsible digital citizens capable of discerning false from truthful information.

“Enhancing media literacy is not just about recognizing fake news; it’s about empowering individuals to critically evaluate information, navigate digital landscapes responsibly, and actively engage in shaping a trustworthy media ecosystem. Without these foundational skills, the Lao people remain vulnerable to misinformation, and manipulation,” said Viphet (pseudonym), administrator of a leading Facebook page.

It’s an uphill climb in a public sphere and media landscape constrained by decades of state control. – Rappler.com

This story was made possible through the #FactsMatterJournalism Fellowship.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.