SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

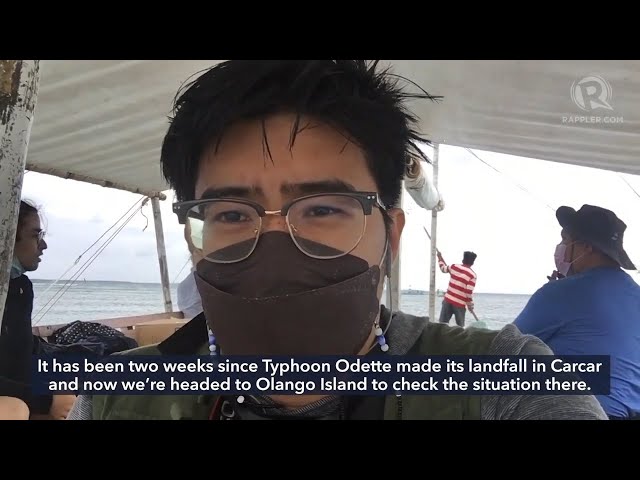

CEBU, Philippines – On Sunday, January 16, a month after Typhoon Odette devastated Olango Island, residents lined up for their first round of P5,000 in financial assistance.

The clouds were dark again. The wind was strong.

But for the first time in a while, on this sleepy isolated island, the people had at least something to look forward to.

It took at least two weeks after the typhoon for the first food relief from government agencies on mainland Cebu to reach the people here.

While Olango is only adjacent to the modern Metro Cebu, life here is much slower.

The disparity between the isolated fishing village of Olango and the bustling Metro Cebu has existed for decades but only became more pronounced in the aftermath of the disaster.

While power, water, electricity, and cell signal have returned in many of the urban areas of Cebu, many of the province’s rural villages remain in the dark.

Odette’s destructive winds wrecked the only port capable of docking large ships and RO-ROs (roll-on roll-off barges).

Bringing aid here has been a logistical nightmare for local government and non-governmental organizations trying to deliver the much-needed help for the residents.

The island’s geographic isolation has been a perennial challenge for the local government to take care of the needs of the over 41,000 people who live here, only pronounced further by the destruction caused by Typhoon Odette.

“Historically, Olango has always been in the background of Lapu-Lapu and Cebu cities,” University of San Carlos researcher Filipina Sotto wrote in her 1997 paper entitled, “Livelihood and the environment: Inextricable issues in Olango Island.”

At the time, a marketplace or trading center did not even exist. Fishermen’s wives would go house-to-house to sell their shells or fish. More than 76% of the residents lived below the poverty line.

But there have been some signs of progress. There is a small marketplace in Olango today.

Tourism brought about by the renowned bird and marine sanctuary created new employment opportunities and improved the local economy. But the COVID-19 pandemic shut down all of tourism activities in 2020.

Then came Odette.

Whatever little gains Olango had over the past decade were built on fragile grounds.

According to the local government, 85% to 95% of homes on Olango were either completely destroyed or had their roofs blown away, leaving them exposed to the elements for weeks now.

After the wind and rain began to settle in the first two weeks after Odette, the aid began to trickle in. But for thousands of residents without any livelihood or income, the help could not come soon enough.

No livelihood

For fisherman Ronel Sagarino from Barangay San Vicente, not being able to repair his boat means not being able to make a living to feed his family.

“Ang gas tag P10 tag-tumbok. Ang mga bata muinom og tubig unya ang tubig karon tag P15 pero parat. Mineral [water] tag P60. Asa man mig income? Wa man mi ikapalit,” said Sagarino.

(The gas costs P10 per small container. The children drink water, then the water costs P15 but is salty. Mineral [water] costs P60. Where do we get income? We can’t buy anything.)

Prior to the typhoon, Sagarino would fish starting in the late hours of the evening to sell in the morning.

On average, Sagarino said he would earn P100 per kilo from his daily catch. But, without any boat, it would be near impossible for Sagarino to go fishing.

“Wa na mi mga bangka kay nangaguba na tanan,” he said.

(We don’t have any boats because all of them have been destroyed.)

Villagers in San Vicente told Rappler they counted at least 50 fishing boats destroyed after the typhoon.

Sabang Barangay Captain Nelson Melanculico said almost all fishing boats in his village were destroyed.

Many fishermen are still unable to repair their boats because, out of the over 3,000 registered fishing boats on Olango, only 13 had insurance, according to the fisheries office of the local government.

No power, no water

After decades, Olango only began to experience a 24-hour power supply beginning February 2021. But Odette took down the power lines again on December 16.

As of January 19, villages here are still in the dark.

Mactan Electric, the power provider for Lapu-Lapu City and Olango, estimates some areas may not get power back until the end of February.

For some, the lack of power may be a matter of inconvenience, but for elderly residents and others who are prone to health issues, no electricity can be a matter of life and death.

For three days from January 1 to 3, Nene Ompad from Barangay San Vicente searched for a place to plug in her nebulizer. Unable to find any place to charge the only machine that could keep her out of the hospital, she was admitted to the hospital for an asthma attack. Even houses with solar chargers could not power up because the skies had been cloudy for almost two weeks straight.

Residents of Barangay Sabang shared how a senior citizen died after the typhoon after he was unable to go for dialysis due to the power outage.

The cell signal tower coming down, coupled with the power outage, has made emergency response even more difficult.

Signal is sparse – and emergency medical services have become limited.

Santa Rosa Community Hospital, the island’s only hospital, is running on a generator. When Rappler visited on January 2 at around 6 pm, the small emergency room was completely dark.

Olango’s only sea ambulance was also badly damaged by the typhoon, making it difficult to transport patients to better-equipped hospitals in Mactan or mainland Cebu.

Local government, private groups scramble to help

In the first two weeks after Odette, the local government of Lapu-Lapu focused most of its attention on responding to the needs of the barangays in mainland Lapu-Lapu.

“Here, on the Mactan side, you can ride the boat, but you’ll have to step in the water because the port was completely broken,” said Alex Baring, the city’s special director for environmental concerns and head of the city’s agriculture and fisheries office.

According to Baring, the damage to the agricultural and fish industry on Olango alone is at an estimated P38 million.

Barangay chief Melanculico only began distributing to his village of almost 7,000 residents the aid from the Department of Social Welfare and Development on January 1. He said then that the little aid coming in was still not enough.

“Aside from people remaining homeless, the food we received is not enough,” Melanculico said in Cebuano.

By the third week of January, Lapu-Lapu City Mayor Junard Chan was able to strike a deal with neighboring Cordova town to allow the use of its RO-RO port while the Angasil port in his city had yet to be repaired.

This allowed food, water, solar street lamps, and construction materials to be brought in to – hopefully – speed up Olango’s recovery.

Rappler visited Chan’s office, called him, and texted the City Social Welfare and Development Office to ask about the recovery process so far, and specific plans moving forward. We have not yet received a reply as of this writing. We will update this once the local government responds.

Private groups have stepped in to make up for the void in aid coming from government agencies.

Non-governmental organization SEED4COMM was able to deliver at least 60 solar lamps to families on Olango Island. They were also able to deliver food, water, and construction materials with another group called CollaboX.

A group formed in April 2021 called “Dispensilya Sugbo” (Cebu Pantry), led by well-known writer and actress Bambi Beltran, was able to already deliver drinking water, rice, canned goods, noodles, instant formula, Aquatabs (water purification tablets), and used clothes to 269 families in Sitio Bunga in Barangay Santa Rosa.

The situation in Olango is only one example of many that were hard hit by the typhoon in the Visayas and Mindanao.

According to a statement by Alibyo Cebu, an organization working on relief in the southern towns of the province, they have been to dozens of communities that have yet to receive any form of aid from the government.

“There is also no clear plan for rehabilitation and recovery for typhoon-affected communities, particularly low-income sectors,” they said in a statement on January 16.

But for families in Olango, being in the background and behind other cities in the province is nothing new.

Dioscora Ompad, 72, who has lived on the island all of her life, told Rappler in early January that the simplicity of life in Olango was the very reason why she had never left to live in the city, where there were more opportunities.

“We had just enough here,” she said in Cebuano. “To tell you the truth, if this typhoon didn’t hit us, we wouldn’t be struggling this much.”

While waiting for aid, Dioscora said that she had been praying: “I pray that people can go and make a living. That help comes. And that people of Olango find grace.” – with reporting by John Sitchon/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.