SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When Mariza Hamoy felt lost, she looked to Darwin.

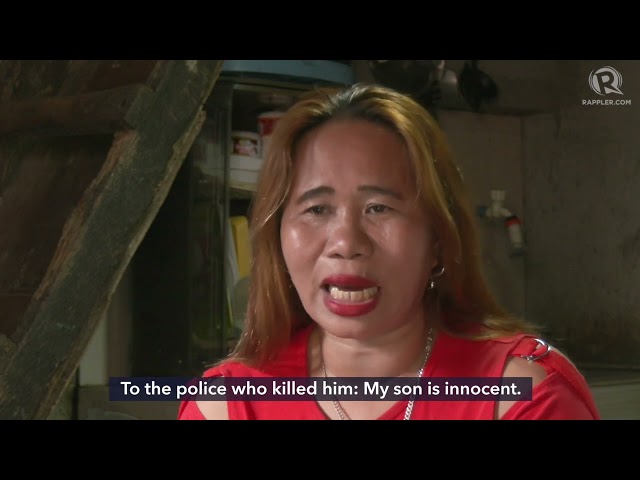

Mariza was a street sweeper from Payatas, that part of Quezon City known for its dumpsite. She was plump, had a boisterous voice, and was thorough with her work. Darwin was her son – lanky, tall, studious, and, at 17, wise for his age.

Mariza would ask him, “How should I budget what we have left?” Unsure about what to feed the family, she turned to Darwin, “What should our dinner be?”

Darwin said he wanted pork sinigang – his favorite – and that they should buy the meat a kilo at a time to save. Mariza bought the groceries and Darwin went home with pockets full of change from helping elders carry their finds at the local market.

Mariza could not afford to send Darwin to regular school, so he only had classes on weekends. In his free time, Darwin worked, aiding his mother, who had five other mouths to feed.

They shared a difficult life in Payatas, living inside a house with tarpaulins for walls and a thin cloth for a door, but they were complete.

In August 2016, a month into the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, Darwin was shot dead in a police operation. The police said he was a threat.

Lost, Mariza talked to him again, through prayer. “What should I do?”

She gathered the courage to file a complaint against the policemen who killed him, whispering to herself, and to Darwin, “I will give you justice.”

When I asked for an interview with her in December 2021, Mariza again looked to her son.

“Son, I’m sorry you’ll be exposed on TV again. I need this because I am fighting for your case. It can’t be that you’re not exposed,” Mariza whispered to him, now ashes in an urn after he was exhumed and cremated in October.

“Even when you’re not here anymore, you’re famous. Imagine that!”

The night they took him

When Darwin was still alive, Mariza took him to a wake in Payatas late in the evening of August 14, 2016.

Mariza gathered with the women in a vigil, and Darwin, bored, asked if he could be excused to play in a nearby computer shop. Mariza let him.

Around 15 minutes past midnight on August 15, Mariza heard unmistakable pops. Gunshots.

She flinched, but did not worry. Mariza had no reason to suspect anyone she knew would be a victim of the new police. It was at the start of President Rodrigo Duterte’s promised campaign to clean their community of drug addicts and criminals. She knew they were being killed, but she was acquainted with none of them.

Everything was alright until Mariza left the wake and found no Darwin home. Frantic, she woke her husband to start a search.

Mariza returned to the wake, asked if they saw a young man along their way. She walked farther, circling the area, asking again and again: “Have you seen my son?”

Near a computer shop, she was told by residents that some men had been shot and killed by cops just that night. Her son might have been among those killed, one of them said.

Mariza refused to believe them, but a small part of her also thought the unspeakable could be true. She went to the police station. There, she was told her son had been killed.

Mariza only saw Darwin two days later on August 17 – dead, caked with makeup, and enclosed in a casket.

According to the police, Darwin was killed for posing a threat to their lives after he participated in a pot session in a house no more than 100 meters away from where Mariza was whispering Hail Marys.

Past midnight, August 15, police raided the house of Cherwen Polo, a tricycle driver, then killed him and the men they claimed were inside with him: William Bordeos (also known as Blink), Sherwin Ternal, a certain “Ramboo,” and Darwin.

The police said the men fought back so they had to retaliate – they were among the first cases where these twin tropes of threat and self-defense were used by the police to justify killing suspects to protect themselves.

There was one survivor of the raid, Harold Arevalo, but he could no longer be reached by witnesses.

For Mariza, the police’s report was a load of lies.

How could her son, still a minor, shoot it out with cops when he never held a gun in his life? How could her son, smart both in school and in the streets, be foolish enough to deal in drugs and face cops head-on? How could her son, who has never hurt her, attempt to take the life of another, let alone an armed policeman?

She did her own investigation, but found out little. According to Cherwen’s neighbors she spoke with, Darwin was beckoned to buy cigarettes by a man in the vicinity and that was the last they saw of him.

The same questions swirled inside the heads of the women who knew the dead.

Kathrina Polo, Cherwen’s wife, knew her husband was innocent. She was there when the cops shot the men, and she was willing to testify.

A fighting chance

Kathrina offered all she could recall in a testimony on the day of the police operation. A policeman from the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group interviewed her. This was what she said:

The massacre started at 11 pm on August 14, 2016.

She arrived home and saw on the second floor that Cherwen was drinking with his friends Ramboo and Blink. She also saw two other drinking buddies she did not recognize. It was not a shocking sight as Cherwen was only celebrating his birthday, which was on August 12.

She proceeded to the ground floor to mix powdered milk with water for her and Cherwen’s youngest child when she saw someone open the door and a group of men carrying “guns and armalites” storming into their house, hurrying to the second floor, then shooting the men above.

Kathrina shouted that children – three of her kids – were with her downstairs. A man above shouted back that she should leave their house. Now. On their way out, Kathrina saw the men roughly inspecting their home’s cabinets. Two more gunshots.

She was ordered by one of the men again to leave, and was told to stay at a place far from their home. Rattled, Kathrina rushed her children to her brother’s house.

Kathrina could not sleep and returned to their home at around 4 am. The house was in disarray, the floors awash in blood. Cherwen and the men with him were already dead and taken to a funeral parlor.

In later interviews, Kathrina declared that Cherwen and all the men with him did not fight back, contrary to what the police claimed. Cherwen may have used drugs, but he did not carry a gun, and if he had, he would not have used it against the cops. He just turned 38.

The reversal

Kathrina was crucial in the case against the police because she was the only adult witness who was not suspected by the police of wrongdoing.

Along with Marilyn Bordeos – the aunt of William – Darwin’s mother Mariza filed a case with the Ombudsman, the Commission on Human Rights, and the Philippine National Police (PNP) Internal Affairs Service (IAS) in 2017.

Together, they rode jeepneys from Payatas to Camp Crame and to the Office of the Ombudsman, testifying where they had to testify, speaking to reporters, and hoping for the best.

But Mariza said their trust fell apart. While she continued to avoid and lambast the police, both Marilyn and Kathrina appeared to grow closer to them. Mariza accused them of giving in to the police, accepting money and working as informants for the cops. In text messages to Rappler, both Kathrina and Marilyn denied Mariza’s accusations.

The two stopped talking to her and stopped appearing with her in their hearings.

Kathrina and Marilyn recanted everything they said against the police. Without giving proof, the two women in their latest testimony in June 2018 said they were bribed by reporters to make up stories about what they saw that deadly night. Like the survivor Harold, Kathrina and Marilyn became unreachable, even to Mariza.

Mariza’s heart sank. She felt abandoned. In a matter of months, the case at the Ombudsman was dismissed for lack of evidence. The three jointly filed the case and it could not stand with just Mariza left on the stand. She was not there when it happened. Kathrina was. But she was gone.

The three filed separate complaints at the IAS. While Mariza’s case remained, the two had withdrawn theirs.

I asked Mariza what she planned to do next. She did not know. She had no lawyer to guide her.

She remembered having one, she said, but she was no longer in contact with him. Someone promised to help her, she said, but she had not heard from that person either.

It was back to her and Darwin.

The impossibility of justice

Seeking justice in the Philippine drug war almost never comes to anything.

Of the thousands of killings both by police and vigilante shooters, there has only been one case where victory for the victims was declared: the convictions of policemen in the killing of Kian delos Santos.

Kian was a schoolboy slain in a one-time, big-time operation in Caloocan City in August 2017. He was killed at 17, just like Darwin.

His was the only case where a neighborhood surveillance camera caught cops dragging a victim towards a dark alley moments before his death – a private execution.

The video went viral and the case was buoyed in the national agenda by public outrage. In a little over a year in November 2018, the three policemen in the operation were convicted of murder.

The Duterte government was quick to call Kian’s case an isolated one, even claiming the conviction of the cops was proof that the Philippine justice system was working. It was a glaring falsehood for Mariza.

Mariza was one of the few others who believed their loved ones were murdered too, but had no video or the public to back them.

“I have no video. My video is inside my heart and with the Lord. The truth will come out,” Mariza told me.

Five years later, the policemen in the operation that killed Darwin were promoted and reassigned to different police stations. The station police chief, Lito Patay, was assigned to the powerful Criminal Investigation and Detection Group, and, as of January 2022, he has become the chief of comptrollership for the Davao Region Police.

The chief of the Quezon City Police District at the time, Guillermo Eleazar, went off to become the chief of the country’s entire police force before retiring in 2021. He is seeking a senatorial seat in 2022.

As she fought to appear in hearings, Mariza claimed she and her family were harassed to submission.

Their barangay (village) hall, where she held office, has become a site of policemen seeking to strike a conversation.

One of them – she recalled the conversation but not the name – said that she should just demand P50,000 from each policeman she accused. The cop wrongly computed and declared: “Magiging milyones ka na (You will become a millionaire)!”

The flustered Mariza replied: “Sir, I do not need money. I am used to being penniless. Let us see each other in court.”

“Tell your friends, what if I shoot their children and just tell them I could pay? What they would feel is what I feel,” she said.

Mariza’s husband, Danilo, has also been arrested twice, in 2017 and in 2021, based on charges she said were fabricated by the police. In both instances, he was accused of illegal gambling. The first time, he was accused of possessing illegal drugs, a claim that was dismissed.

Mariza told her husband to be more careful, but she said she was not giving up. She will not surrender, she said, even until the day she dies.

She promised Darwin.

“Don’t worry. You may be dead, but, to me, you are alive. Win or lose, I will fight for you.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Uncle Bob] No whores at the Oarhouse](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/oarhouse-june-28-2024-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.