SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

José Bula Moreno, a 23-year-old law student, was a teenager when he knew he wanted to pursue politics. For four years, he has been preparing for the regional elections in his hometown of Puerto Libertador, a small city in northern Colombia. The runoff, later this month, will decide whether he wins a seat on the municipal council.

Meanwhile, Espedito Duque, 57, who is a local political fixture with an opposing party and more than a decade of experience, is seeking a political comeback and running for a second term. Despite these men’s disparate backgrounds, the elections will unfold under the shadow of one man: the journalist Rafael Moreno, whom a local gunman assassinated one year ago this month.

José Bula, Moreno’s nephew, now uses his political platform to honor the legacy of the man he considered a father. “There’s not a speech I’ll recite without naming him […] it’s inconceivable to forget the good he did for our city,” José Bula said.

Known by locals as“the people’s voice,” Moreno covered Córdoba, a region in northern Colombia, investigating corruption and environmental crimes despite persistent threats. One of Moreno’s riskiest investigative targets was Duque, the mayoral candidate and head of the city’s most powerful clan, the Duque clan.

In early October 2022, Moreno contacted Forbidden Stories to store his work with the Safebox Network, a system designed to protect journalists’ most sensitive information. If a journalist is killed, kidnapped or imprisoned, Forbidden Stories and its media partners can continue their work and publish their findings. He had called Forbidden Stories from San José de Uré, where he found that companies were exploiting materials from the Uré River basin without any permits or licenses. Moreno was murdered 9 days later.

Despite investigators in charge of the case having access to photos of the hitman who killed Moreno (published for the first time by Forbidden Stories), the criminal investigation into Moreno’s murder appears to have stalled, and no one has been arrested to date. Many of the region’s journalists have stopped investigative reporting for fear of retaliation; some have fled the country.

The day after Moreno’s assassination, Forbidden Stories and its partners began a collaboration with 30 journalists to continue Moreno’s work. In Part One of “Rafael Project,” the consortium uncovered a system of favoritism in awarding public contracts worth more than 3 million euros during Duque’s administration. Between 2016 and 2022, the Duque and Eder John Soto administrations signed 99 contracts with 13 businesspeople close to the Duque clan. No official investigation has been opened against Duque, one of the men at the heart of this system of favoritism, according to Forbidden Stories’ sources.

Now, in Part Two of this project, one year after Moreno’s assassination and two weeks before the local elections, Forbidden Stories and Cuestión Pública resumed Moreno’s last major investigation. Through documents and testimonies, the consortium was able to confirm Moreno’s hypothesis that natural resources were being illegally extracted from the San José de Uré river, pointing to several high-level politicians in the Córdoba region.

A river emptied of sand

In January 2020, Moreno visited San José de Uré, a small town at the foot of the Paramillo Natural Park in northern Colombia, where much of the population lives off agriculture and fishing, to report on the tourism industry. In a video filmed during the visit, with accordion music playing in the background, Moreno stood in front of a pebble beach, praising the crystal-clear gorges: “As you can see, people come here to enjoy themselves, enjoy a meal with family and friends,” he said.

Still, despite its appealing summer season and apparent calm, the city of just under 15,000 inhabitants saw 62 homicides in 2019. San José de Uré is controlled by the ‘clan del Golfo,’ one of the fiercest armed groups in Colombia and responsible for most of the crimes in the region.

Two years after Moreno’s visit, he received tips from locals: hidden behind the city’s arresting beauty, illegal extractions were taking place. Moreno set out to investigate: he traveled along the river several times, interviewing locals and filming incessant truck traffic–vehicles loaded with sand extracted from the river basin. In a video clip, taken during one of several reporting trips in 2022, Moreno condemned the widespread and “illegal” plundering of sediment and sand from the river around San José de Uré, a village of some 12,000 inhabitants.

“There are four or five diggers working day and night [to extract resources from the river]. It’s a disaster,” he said during his last call with Forbidden Stories. “They are doing irreparable damage to the basin, which is part of our region’s cultural and natural heritage,” he said. Moreno and colleagues filmed several videos from extraction sites, documenting excavators damaging the river and turning its banks into a construction site. They shared the footage on social media, which circulated widely.

During follow-up interviews by Forbidden Stories in the region, locals described the extraction’s damage to their livelihood. Felix Peñate Amor is a social leader–a term referring to human rights activists and community leaders–from Versalles, south of San José de Uré. His family is one of roughly 100 living in the village for whom the river is a primary source of income and food. “Almost all of us are fishermen and farmers,” Peñate Amor told Forbidden Stories. “The river’s level has significantly declined since trucks started coming through, running us dry,” he said. The water, he added, had become contaminated. The engine oils and lubricants from trucks persist in and around the river, and the excavators have muddied the once crystal-clear waters with sediments from the shallows. “We can’t drink it anymore; it’s almost like mud,” Peñate Amor said.

As he investigated, Moreno became convinced that this mix of rocks and sand plundered from the Uré river was being used to build roads around the village. Moreno hypothesized that some companies responsible for road infrastructure were using the river’s resources to cut construction costs. He sent public information requests to the municipality of San José de Uré and the regional environmental management body called CVS, a process that grants access to internal administrative documents.

In October 2022, Moreno, who had also become a social leader in his region, and a colleague filed a criminal complaint with the Córdoba prosecutor’s office. They denounced the “illegal exploitation of mineral deposits and other materials” and called for an urgent investigation “to safeguard the environment, public finances, health and road safety of the inhabitants of the municipality of San José de Uré.”

Ten days later, Moreno was closing his shift at Rafo Parilla –a fast-food restaurant where he worked part-time to support his wife and three children – when a gunman entered and killed him.

Wild extraction

One evening in May 2023, Yamir Pico, Moreno’s cousin who had collaborated on his investigation, found himself at home alone in his apartment in Montelíbano, a town in Córdoba. His bodyguards had just left when he heard a sudden clamor. Two hitmen had broken through his door, pointing guns in his direction. “One told me, ‘We don’t want to kill any other journalists, but the next time you touch the San José de Uré affair, you’ll be dead,’” Pico recounted to Forbidden Stories.

The men confiscated his work equipment, including his computer, notes, and two USB keys that Moreno had given him before his murder. Two days later, Pico secretly fled the country with his family and now lives in the United States.

Pico was part of a small band of journalists, local leaders and environmentalists who worked with Moreno, providing information and on-the-ground knowledge, who’ve since had to flee or abandon their work. Pico had published his findings on Caribe Noticias 24/7, a site that covers local news.

“There is not a more dangerous subject,” Walter Álvarez, a journalist and friend of Moreno’s, said. Álvarez also participated in the investigation, accompanying Moreno on his reporting trips. In August 2023, Álvarez’s eldest son, 22, was killed in the town of Salgar in the department of Antioquia, where he was visiting his mother. “I can’t see any other reason except that they wanted to shut me up,” Álvarez said. “But I had stopped investigating.”

One month later, Álvarez received a WhatsApp message from an unknown number. “You will soon be keeping Rafael Moreno company. You and your bodyguards. We are going to kill and burn you.”

“People think it’s a small story. In reality, it is a huge embezzlement system of public money and resources, involving many politicians,” Pico said.

According to information the mayor of San José de Uré, Custodio Acosta Urzola, shared with the consortium in response to requests for comment, between 2021 and 2022, he signed a series of contracts with several companies specializing in public works. The goal was to build and improve roads to open up the small, isolated community. These 20 contracts totaled 15 million euros (68 billion Colombian pesos).

Several months after those contracts were signed, locals started denouncing the extractive activities. For years, they had witnessed the rural Versalles zone, including the river and surrounding area, deteriorate, as the river banks transformed into an extraction site. There, Consorcio Versalles, a local construction company, had been given a mandate by the Municipality of San José de Uré to “improve an access road via the construction of a hydraulic concrete covering,” as written in the contract.

For Moreno and colleagues, this geographic proximity between the extraction and road construction sites is hardly a coincidence. Through several online posts, they denounced Consortio Versalles for committing an “environmental crime.”

One month after Moreno’s assassination, following a complaint he filed several days before his death, the regional environmental management body called CVS opened an investigation and sent a team on site.

The February 2023 report, kept internal but obtained by Cuestión Pública, confirmed Moreno’s observations, including the existence of illegal extractions and environmental damage and placed responsibility on Consortio Versalles. Members of CVS noted “traces of extraction in the bed of the river […] This seems to have been carried out without the required authorizations and permits, which is worrying for the ecosystem and the local population.” In February 2023, CVS ordered an administrative investigation against the municipality of San José de Uré and Consorcio Versalles.

Consorcio Versalles did not respond to Forbidden Stories’ request for comment.

“Construction workers started the work a year after signing the contract,” social leader Peñate Amor said. Residents of Versalles claim the road still appears under construction today, despite the 2021 contract stipulating a one-year deadline.

Consorcio Versalles is one of many companies that illegally extracted material from the river, according to several sources close to the affair. “Rather than buying certified construction materials, which cost a certain price, companies [hired by the municipality] enter into an agreement with politicians to extract natural resources for free, without a permit. The money is then shared between these companies, the mayors, and the Clan del Golfo,” Pico found in his reporting. “It represents a fortune. That’s why they are ready to kill anyone,” he said.“It’s why they sent two sicarios [hitmen] to my house,” he added.

San Jose de Ure in the crosshairs of clans

The natural resources of the San José de Uré region appear to have attracted several political clans vying for power in Córdoba, including the influential Calle family. The family owns “finca Marcelo,” a vast property that borders the river. Shortly before his death, Moreno filmed himself live from the farm, accusing the Calle clan of participating in extraction activities in the area.

One of the family members, Gabriel Calle Aguas – former campaign director of President Gustavo Petro and candidate for the government of Córdoba in this month’s regional elections – announced earlier this month that he hoped to make San José de Uré a hub of industrial production.

When contacted by the consortium in April 2023, Gabriel Calle Demoya, father of Gabriel Calle Aguas, denied any responsibility for sand extraction, blaming the companies that carried out the work. The family patriarch also told Forbidden Stories that it was the regional deputies who should be looked into.

Although the Calles have a vested interest in the area, the consortium’s investigation on illegal extractions in San José de Uré uncovered other leads. Sources, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution, identified several local figures, including the current mayor of San José de Uré, Custodio Acosta Urzola, the subject of an administrative procedure that Moreno initiated to obtain information on the extractions; his cousin, Luis José Gonzalez, former mayor of the city and candidate in the upcoming municipal elections and who occupies a property on the extraction zone.

José Gonzalez did not respond to Forbidden Stories’ request for comment.

In a lengthy letter to Forbidden Stories, Urzola asserted that mining activities are monitored by the Ministry of Mines and Energy and that “the municipality [of San José de Uré], through the Planning Secretariat, implemented measures to end this type of illegal mining”

He did also confirm that he visited Rafo Parilla, Moreno’s fast-food restaurant, the day before the murder. The conversation “was pleasant,” according to Urzola, because he and Rafael had been friends since 2019.

“That day, he told me about his plan to go back to school (…) I bought him some meat and left a gift for his daughter,” he said.

Erasmo Zuleta, a highly influential political figure in the region and current candidate for governor of the Cordoba region, running against Gabriel Calle Aguas, was another name mentioned by sources close to Moreno.

Widely favored for the upcoming local elections, Zuleta was a deputy in the House of Representatives from 2018 to 2022. He belongs to one of the most powerful families in Córdoba, the Becharas, and he was the coordinator of the National Development Plan, which implements strategic projects in different regions, from 2018 to 2022 for the department of Córdoba. “Zuleta was a deputy when the contracts were signed in San José de Uré. It is at this level that it is decided where the money goes and which are the priority municipalities,” an expert on the subject said.

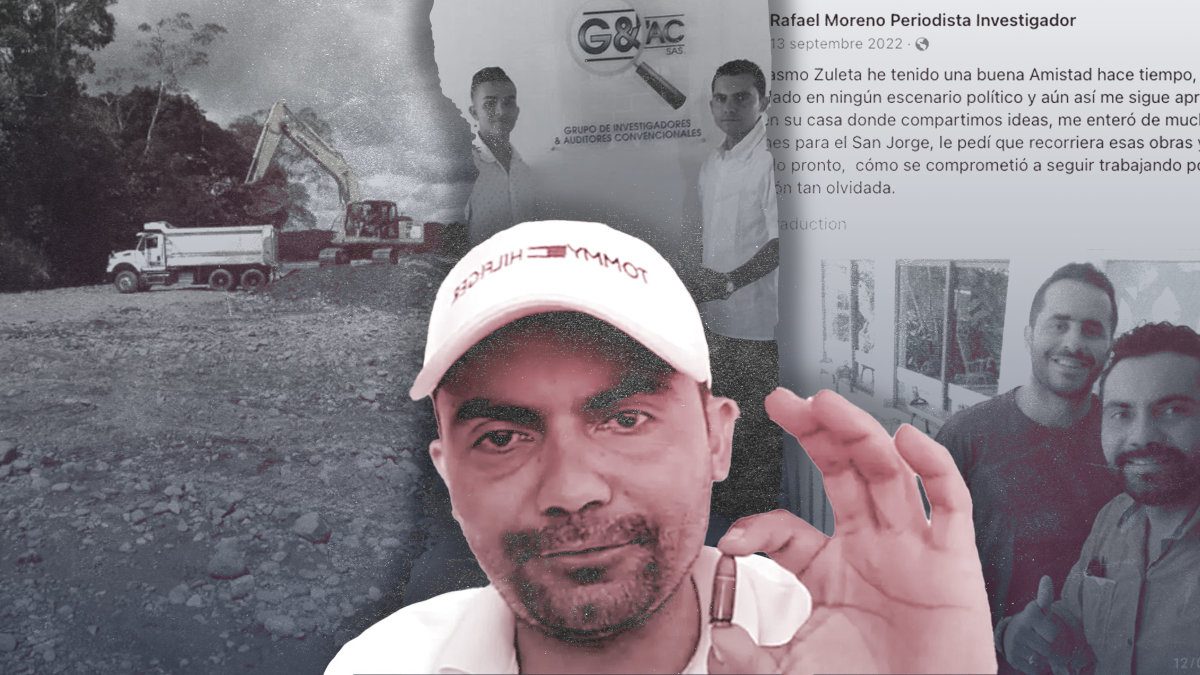

In September 2022, just over a month before his death, Moreno spoke to Zuleta, whom he referred to as a friend on social media. “We exchanged ideas, I learned about the many efforts he made for San Jorge,” (the name of the area around San José de Uré) a post published by Moreno read alongside a selfie of the two men. In response to our findings, Zuleta told Forbidden Stories he has few links with the region and strongly denied discussing illegal extractions with Moreno.

Many questions on Moreno’s last investigation remain unanswered, and each new lead raises more questions.

A year after Moreno’s murder, his killers remain on the loose. “Things are getting worse, and I really wonder where justice is […] I would like his work and his investigations to continue to have an impact here after his death,” his nephew, José Bula, said. The upcoming elections, he continued, “will be a moment of truth,” and a test of whether Moreno’s death has marked a turning point in the region. – Rappler.com

This article has been republished with permission from Forbidden Stories.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Judgment Call] Who’s after Quiboloy? The media should be.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/judgement-call-quiboloy-media-2.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=484px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.