SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Old methods, new platforms: The Philippine military on social media](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/10/FB-Takedown-Army-accounts-October-2-2020.jpg)

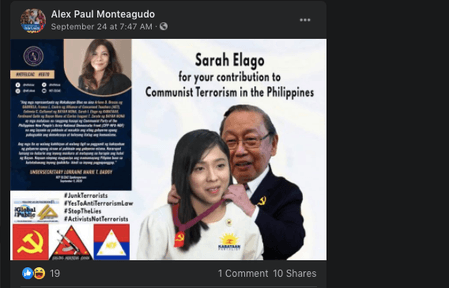

On the day Facebook announced the removal of dozens of pages and accounts across its platforms, I received several private messages from contacts in the Philippine military. As I responded I stated a caveat that while I kept tabs on social media content policies, I do not work for a social media company. There were queries about which identification cards or documents Facebook accepts to validate a person’s identity. At some point in one conversation, I asked along the lines of, “Bok, naka-on ba ang 2FA (two-factor authentication) ng account mo? (Buddy, is 2FA activated in your account?).” I was answered by an earnest question: “Ano yung 2FA? (Whats 2FA?)”

Seizing the initiative in the information space is a longstanding mission in the Philippines, even before social media. Shaping public opinion falls within the broader mission of “civil-military operations” (CMO). For a country like the Philippines, beset by multiple internal conflicts, the information environment is a muddled mix of offline and online, analog and digital, new and traditional media. A cursory look at Facebook pages associated with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) highlight ad hoc fusions of effort. Aviators would share videos of leaflet drops; CMO officers posting clips of loudspeaker operations mounted on Army trucks; civil relations personnel livestreaming AM radio broadcasts. These examples suggest a military that is adaptive and adept to the changing information environment.

Western militaries, particularly NATO member-states and the United States have publicly accessible manuals and doctrine that state what is permitted behavior and content on social media. Details differ when it comes to preserving operational security, but most are premised on online non-partisanship. US DOD personnel are reminded of the Hatch Act of 1939. In the Philippines, there are only nebulous mentions of a purported 2016 AFP policy on social media dated sometime in 2016. Lack of transparency over the AFP’s activities on social media underscores the common and accepted practice of identity obfuscation. Proponents would argue that a degree of deception is necessary to protect military personnel from physical harm such as targeted assassinations. Obscuring one’s identity on social media is also considered a way to prevent opponents from gathering information that could be used for vexatious litigation.

Over the years, I would notice how military friends would use backwards-spelled versions or anagrams of their real names as FB profile names. There is also the common practice of using the first syllables of surnames affixed with an “s” — one permutation of an obscured name for myself would be “Jo Franks.” Facebook’s September surprise did not mention it explicitly, but I suspect some of the suspended accounts did not comply with existing rules on the use of real names.

Lack of appreciation for current social media regulations can also be found on institutional accounts of the AFP. A couple of days after the September takedowns, I looked at the various FB pages used by the AFP. Nothing has changed. Only the main AFP page along with the 3 major service commands (the Army, Navy, and Air Force) had that blue tick mark — denoting a verified account for their accounts. All the AFP Unified Commands were unverified. Only the 1st Infantry Division (Team Tabak) was verified, while the 10 other infantry divisions lacked the blue tick and were haphazardly categorized as “government organization,” “government building,” or “government service.”

Personal FB accounts were misused, wilfully or not, as institutional pages. It is amusing to see special operations battalions, Air Force wings, or CMO from all the major services popping up on one’s list of “Mutual Friends” or as “People You May Know.” But it is also evident that there is a lack of understanding how identities work on social media. The uneven presence of the AFP on social media seemed to underscore that the priority was to get into the space quickly by any means. Hearts and minds moved into Facebook and Instagram. Tactics reminiscent of the nineties and the early oughties such as “text brigades” and “SMS blasts” were appropriated for AFP social media campaigns. Overlaid are both overt and covert campaigns to get AFP personnel, along with their friends and families who were exhorted to like, share, and follow pages. The organization leveraged on its offline human networks in an attempt to replicate social connections online.

Obscured identities combined with the multiple efforts to increase online engagement, however, was not too far from previous episodes of coordinated inauthentic behavior documented by Facebook. Given the inherently controversial and politicized nature of content moderation, social media platforms have largely swerved towards moderating behavior. Taken together, it was probably very hard for the algorithms to distinguish those illicit networks from the AFP’s nascent attempts to build engagement.

It is unlikely that the current debacle would lead to an honest introspection in terms of how the military and its allies operate in social media. Open and inclusive conversations seem to have been already pre-empted. Among the current narratives being pushed by some commanders is the trope of communists “infiltrating” Facebook’s moderation teams. Or how alleged anti-government activists have somehow duped social media platforms, global organizations with users numbering in the billions. President Duterte has himself brandished the prospect of banning Facebook altogether – perhaps an improbable and counterproductive option, considering the resources Manila has sunk to build a network of influencers to push whatever is the government’s agenda-of-the-day.

Thinking beyond presidencies, the military should go beyond recasting old methods and modes of thinking. Tough talk and swagger — pagiging ‘magan at siga — was never enough to shape the information space when the skirmishes between narratives unfolded in traditional media. It is even more out of place in today’s complex social media environment. – Rappler.com

Joseph Franco is Research Fellow at the Center of Excellence for National Security at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He studies best practices in countering violent extremism and addressing the non-ideological roots of conflict.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Rappler’s Best] US does propaganda? Of course.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/US-does-propaganda-Of-course-june-17-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=236px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.