SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

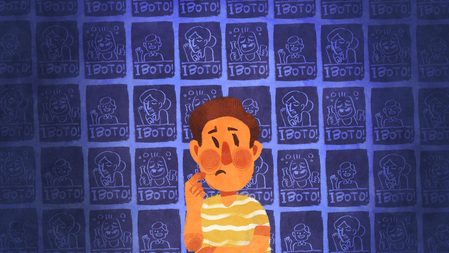

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg)

On the eve of the 2023 barangay elections held last November, my mom wondered: “Ano’ng barangay ba tayo?”

“Molino three,” I said, initially reading out the barangay number in English. “Barangay Molino tres.”

She paused for a few seconds, wondering which parts of upper Bacoor City exactly comprised the barangay we kept writing in forms, before concluding: “Importante pala ’yan, ang laki ng sakop.”

Barangays in theory

I was always taught in high school Social Studies (Araling Panlipunan) classes that “the barangay is the smallest unit of government.”

In many places around the Philippines, this still rings true.

A barangay is usually a neighborhood with a distinct identity. The barangay captain, who heads the local government unit (LGU) of the same name as the neighborhood, is a local known to many families, and a barangay by itself in one’s address can thus easily identify your lifestyle, livelihood, and socioeconomic class. Said barangays are communities first, local government districts later.

Barangays, inverted

The concept of a local government unit below the municipal level is certainly not unique to the Philippines, and like elsewhere in the world, it can be reused for a different purpose: barangays that serve as statistically or politically convenient government districts first, and communities later.

In old historic cities, such as Manila, Caloocan, and Pasay, a barangay is a small, tight-knit community consisting of a city block or two. This explains the three-digit numerical barangays often featured in noontime shows like Eat Bulaga, and the popular catchphrase “Isama ang buong barangay!” which would not be possible in my part of the metro.

Can you tell me what Barangay 666 in Manila contains? What about Brgy. 420, or Brgy. 123? Those are all real and existing barangays, per Philippine Statistics Authority data.

Further down south, cities like Parañaque, Las Piñas, and Bacoor developed the other way around. Rather than having the meticulous city-wide grid plan and four-digit house numbers Manila had, our cities developed as agricultural and greenfield lands converted into real estate developments, all exiting out into farm-to-market roads converted into city arteries.

With each residential subdivision comes a developer’s urge to slap their brand name for easier marketing, and subsequently a desire to maintain each subdivision’s environment so they can be used as a reference for future buyers of other projects with the same brand.

In these “sub-urban” places, homeowner’s associations (HOAs) are the perfect way to consolidate control in a given area. While government agencies building housing projects usually turn over all roads and utilities to a barangay — either the existing one, or an expressly created LGU for that community — to avoid maintenance costs, said costs can easily be eclipsed with the higher profit margins private developers can charge.

HOAs, the new kid in town

In an older neighborhood, or a government resettlement project, who is expected to maintain the basketball court? The barangay. What about the roads? The barangay fixes the potholes. The streetlights? Barangays are supposed to install them. Night patrol? The barangay tanods will handle it.

All these amenities and services are expected not of barangays, but of HOAs, by subdivision residents. After all, these oft-unaccountable private companies are usually the physically closest government-like organization in the area, and it is their name and logo that is marked onto every gate, every streetlight, and every phase’s basketball court.

So what then, of the barangay the area is under jurisdiction of? At the end of the day, every inch of land in the Greater Manila Area is under some group of barangay politicians who may or may not live walking distance from your home.

Barangays without identity

No one around me even knows how to pronounce the name of my home barangay properly.

Is the Roman numeral in “Molino Ⅲ” supposed to be read in English, or in Spanish? It depends who you ask.

The official pronunciation, used by politicians in the area as well as local branches of nationwide businesses, uses the Spanish number, “tres.” Along Molino Road, there is a “Molino Tres Proper” branch of the delivery courier LBC. During the BSKE campaign, we were also treated to jingles from loudspeakers of a candidate saying: “ibalik ang sigla at saya sa Barangay Molino Tres!”

But language evolves, and everyone in my subdivision, and every classmate I’ve ever had who lives here, uses English numbers (e.g. “Molino three” and “Molino four”) when asked verbally about their address.

So, it seems the media has adopted the same pronunciation, I remembered from the last time my area went into the news. Gardenia Valley, one of the many townhouse projects built by GSIS for its members in my district, reached national news when its HOA started charging toll fees on vehicles entering its main road, even jeepneys plying a decades-old route going from Molino to Las Piñas.

How did GMA’s 24 Oras report on the area? “Biro ng isang netizen sa GSIS Road sa bahagi ng Gardenia Valley Subdivision, Molino three…”

Barangays that fail to be accessible

I needed a certificate of indigency to apply for an internally-funded scholarship at my university. To get from home to my barangay hall, I needed to get on a 20-minute tricycle ride, and another 10-minute jeepney ride, before getting to their complex.

It certainly was not walking distance, and was far from what I would imagine from “the smallest local government unit.”

There is a Barangay Extension Office along my subdivision’s main road, but aside from being unreliable and incomplete in services offered, it still fails the spirit of the barangay’s mandate of having an LGU close to you.

Up for a break up?

It may seem that the easiest answer to issues of inaccessibility and lack of identity is to chop up the barangay into several parts.

The counterpoint to this could be efficiency. After all, if HOAs already exist and are already mandated to serve their communities, wouldn’t proposed smaller barangays end up as duplicates with split resources?

A split may not also consider the identities of the areas affected. Neighboring Imus City suffered the same problems as Bacoor; farmland was converted into subdivisions that turned rural parts of the town such as Anabu I and II, and Malagasang I and II, into massively populated “superbarangays.”

Today, residents of upper Imus joke about their barangays acting as alphabet soup, with Anabu I chopped into seven alphabetically arranged ones from northwest to southeast: Anabu I-A, Anabu I-B, Anabu I-C, and so on until I-G.

I still believe in the concept of barangays acting as communities first, government districts later. Will Greater Manila Area towns consume suburbia into efficient LGUs, or will they let themselves be consumed by suburbia? – Rappler.com

Luis Imperial studies BS Computer Science at De La Salle University–Dasmariñas. A native of Bacoor, Cavite, he also serves in various student organizations in the university, including the campus radio station 95.9 Green FM, where he is Junior Director for News & Public Affairs.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.