SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Decriminalizing libel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/TL-libel-jan-4-2024.jpg)

Editor Edito Mapayo, of Radio Birada FM Claver in Surigao del Norte, faces up to 10 years in prison if convicted of cyber libel for calling out a local businessman for alleged false advertising; one of three online defamation cases since 2016. He is out on bail.

“Parang nasanay na ako sa mga kaso,” he says. “Binabalewala ko na lang. Kasi lahat ng inilabas kong isyu totoo naman.”

Arnel San Pedro was a correspondent for a Manila-based paper in 2004 when he was accused of libel. He was acquitted in 2021 after what he described as 17 “grueling” years. His newspaper, he said, did not provide him with a lawyer, “so I shelled out thousands of pesos for my defense… Sarili kong gastos.”

Journalists, and citizens in general, have reason to be weary about being charged with libel, a crime punishable by up to three and a half years in prison, and a fine of up to P1.2 million.

For decades, media groups here and abroad have been campaigning for its decriminalization, with little success to show.

What Article 19 means

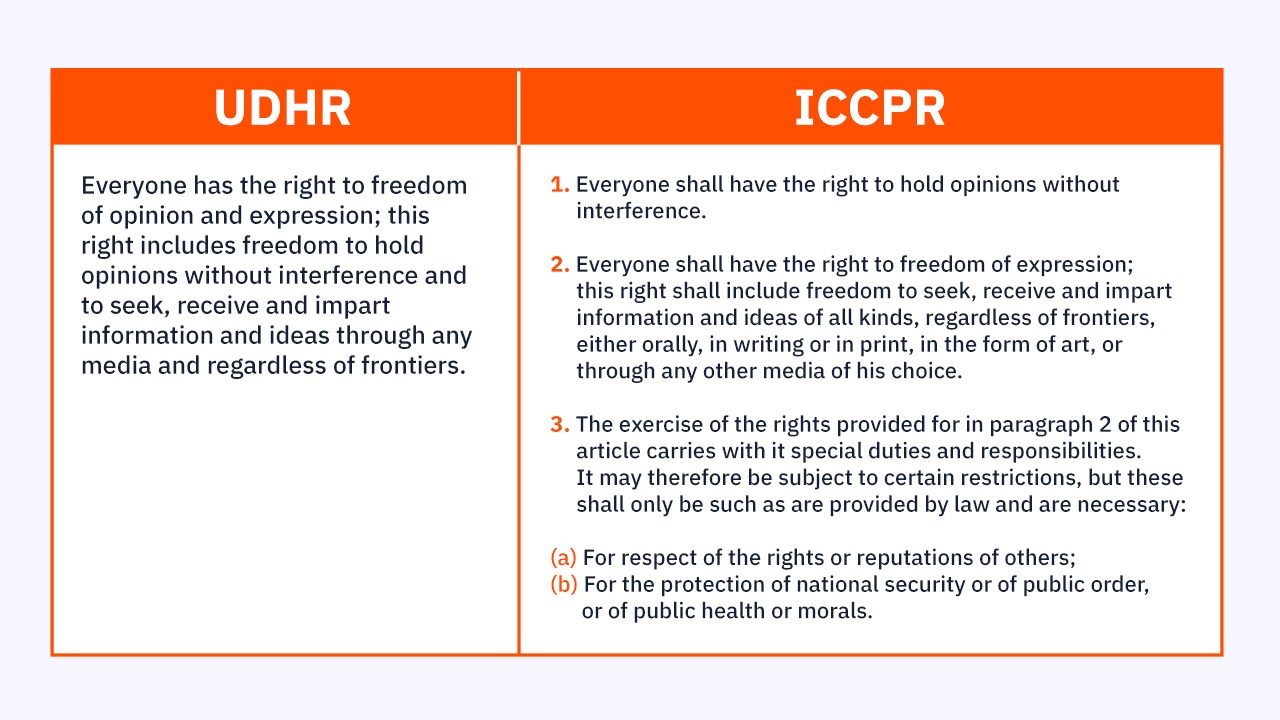

Article 19 of two landmark United Nations documents – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1949) and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) – has come to symbolize, among others, “freedom of opinion and expression.” The Philippines signed and ratified both documents.

In 2008, the UN human rights committee ruled that “imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty for defamation” and that a prison term imposed the previous year on Davao broadcaster Alexis Adonis violated the ICCPR. This opinion eventually led to a court order for Adonis’ release. The UN committee also asked State parties to consider decriminalizing libel.

From 2004 to 2012, Philippine legislators filed more than 60 bills seeking the decriminalization of libel or at least the abolition of imprisonment with regard to libel cases. A total of 35 were submitted in the 15th Congress alone. But the farthest any bill reached was approval on second reading in 2009 of House Bill 5760, whose abstract partly reads: “to allow journalists to do their work without fear of being jailed by reason of criminal complaints by those who are offended by their reporting…”

In 2008, Chief Justice Reynato Puno reminded judges of “an emergent rule of preference for the imposition of fine only rather than imprisonment in libel cases.”

Four giant steps backward

The fight against criminal libel took four giant steps backward from 2012 when President Benigno Aquino III approved Republic Act No. 10175, the Cybercrime Prevention Act, which included libel among cyber crimes if “committed through a computer system.” Step Backward One: the law reinforces libel’s status as a crime.

It also increased the penalty for existing crimes one degree higher. Hence, cyber libel is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. Step Backward Two: from prisión correccional to prisión mayor.

After a legal challenge, the Supreme Court in 2014 upheld the law on cyber libel as valid and constitutional. Step Backward Three: you wake up to realize that the bad dream is for real.

In 2017, RA 10951 raised the fines for libel to up to P1.2 million. Step Backward Four.

While libel convictions are rare in the Philippines, UNESCO contends that criminal libel has “an inhibitory and silencing effect, even before a conviction takes place.” The document cites the impact of these laws in terms of time, financial resources, professional career and image, mental health, deprivation of liberty, and self-censorship.

In acquitting San Pedro, the Angeles regional trial court noted that the item in question cannot be deemed “to have been done with actual malice.” It also emphasized that the material “was true” and “done in good faith.”

Nevertheless San Pedro, now editor of the Pampanga iOrbit said, “Nasayang mga opportunities ko for 17 years.” And money: “P3k per hearing. Four times a year.” Or P204,000, not exactly loose change in a profession not known for fat salaries.

Because libel is a crime, respondents are either jailed or released on bail. Mapayo says he paid a total of P100,000 for his temporary liberty.

But that’s not all. He added: “Minsan naapektuhan [ako] dahil sa schedule sa hearing. Normal [din] lang siguro [na] hindi mawala ang takot sa atin baka biglaang bala ang gamitin ng kalaban.”

Media-citizen councils

Since last year, the Philippine Press Institute has been at work encouraging, assisting and inspiring local communities to set up their own multi-sectoral councils that will entertain complaints for accuracy or the right of reply, in lieu of court cases. These urban, provincial and sometimes regional councils can be found in various stages of development in Batangas, Davao, Iloilo; Aklan, Surigao del Norte; Central Luzon, and Eastern Visayas. Already existing are councils in Cebu (which boasts of a zero-libel record) and the Cordilleras. And more to follow this year.

Participation is not limited to PPI members, or to newspapers, or frequency-based broadcast stations. They are free to include social-media bloggers and other sectors they wish to engage. Following the concept of independent co-regulation, as opposed to self-regulatory press councils, these bodies are free to determine whether the non-media members will outnumber their media counterparts.

The short-term goal is to impress upon the public that complaints against the media will be heard by a group of respected individuals from their communities.

The ultimate goal is still the decriminalization of libel. There are four bills — SB1593, SB2403, HB1769 and HB5372 — in the 19th Congress. If and when libel ceases to be a crime, the councils can become ADR (alternative dispute resolution) providers, properly trained and accredited by the Department of Justice. – Rappler.com

Gary Mariano has taught full-time for 35 years at De La Salle University. A former chair of the Philippine Press Council, he is a member of the Commission on Higher Education’s technical committee for journalism. In retirement, he helps PPI promote community-based, media-citizen councils.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Be The Good] Introducing ‘The Listening Project’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/carousel-4.png?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

The sad thing here is that of all the Presidents, it was former President Benigno Aquino III who caused the four giant steps backward by signing RA No. 10175 (Cybercrime Prevention Act). Although in fairness to him, he is not a lawyer, so who advised him to do it? The Philippine Press Institute may constantly remind our lawmakers to pass the four pending bills in a consolidated law that will decriminalize libel. But more likely, it will be blocked by the combined Repression Machineries of both the Marcos-Romualdez and Duterte Political Dynasties.