SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Newsstand] State of the opposition: Worth dying for](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/08/worth-dying-for-august-30-2022.jpg)

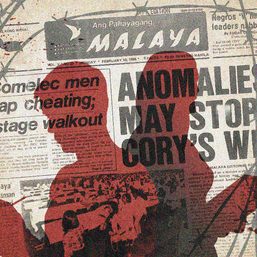

It wasn’t a surprise, but for many who recognize Ninoy Aquino’s heroism, the orchestrated attacks on his legacy on the anniversary of his assassination, subverting the very meaning of his martyrdom, still came as a shock. Maybe it was the brazenness of the deceitful counterclaims, or maybe it was the sheer scale of the networked campaign, or maybe it was the sinking sense that a new nightmare in disinformation and historical denialism had begun – but the blow that shocked many into a defensive crouch was visceral, real.

Can all of that history really be denied? The fact that he was killed by Marcos’s soldiers, the fact that millions of people turned out for his funeral, the fact that his sacrifice galvanized the opposition, the fact that his death in 1983 led to the end of the Marcos regime in 1986: Can all of that be deliberately forgotten, or reinterpreted, or hashtagged away?

Marcos and Duterte allies are certainly trying.

The groundwork had been laid during the Duterte years, when legislation to change the name of the Ninoy Aquino International Airport, the country’s main gateway, was first filed. Alarms over the possible removal of the image of Aquino on the P500 bill (part of the design since 1987) and that of his wife, the late president Cory Aquino (included in the design in 2010), were also first raised under the Duterte administration, when the Bangko Sentral initiated a new currency series that replaced heroes with Philippine flora and fauna.

But the anti-Ninoy campaign grew in volume and viciousness after Ferdinand Marcos Jr. won the presidency. One of the first bills filed in the 19th Congress sought the renaming of the airport from Aquino to the man with final responsibility for his assassination, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos himself, on the mistaken assumption that Marcos built the airport. A day before the 39th anniversary of the assassination, a handful of police accounts on social media used the hashtags #NinoyNotHero (sic) and #NinoyNPA in bizarre posts that were later taken down. And on the day of the anniversary, the coordinated smear campaign against Aquino erupted into full view: He was denounced as a traitor, tagged as a communist, blamed as a destabilizer or a chaos-maker.

And though the August 21 anniversary (which fell on a Sunday this year) remained a national holiday, the main institutions of government kept silent. No statements were issued. In his first State of the Nation Address the previous month, President Marcos Jr. deliberately avoided mentioning Aquino’s name; he spoke of creating “more international airports to help decongest the bottleneck in the Manila Airport.” The policy of official silence on the anniversary, then, was all of a piece.

To be sure, Marcos issued Proclamation No. 42 the day after Ninoy Aquino Day, listing the official holidays for 2023; both August 21 and February 25, the anniversary of the People Power revolution that drove the Marcoses from Malacañang, were still on the list. As I wrote before, I expect it will take him three years to finally drop the two holidays.

But I could be wrong. Of the factions in the ruling coalition, there is at least one that is maximalist; it seeks to rehabilitate the father AND degrade the father’s political archrival as quickly as possible. Republic Act 9256, which declared Aquino’s death anniversary a holiday, can be repealed within a matter of months.

Coalition objectives

Why the zeal to erase Ninoy Aquino from history?

Most of the parties and factions that comprise the ruling coalition, with the possible exception of the marginalized Arroyo group, are invested in reinterpreting mainstream Philippine history because a national narrative that celebrates Aquino as hero is necessarily a narrative that assumes Marcos as villain.

The dictator was gravely ill on the day Aquino was killed; it is very likely that while he approved his wife Imelda’s repeated attempts to warn Aquino against coming back because of the risk of assassination, he did not directly order the killing. He must have anticipated, if not the scale, then at least the kind, of consequences you reap when you turn your rival into a martyr. But Marcos did arrest Aquino when Martial Law took effect; he did imprison Aquino for seven years on made-up charges; he did allow a military court to try, and eventually, convict, a civilian defendant; he did install a dictatorship that denied Filipinos their basic freedoms; he did create the conditions that by the early 1980s had pushed the country to the brink of social upheaval; he did manufacture a subservient military that produced the soldiers who killed Aquino.

Marcos bears final responsibility for Aquino’s sprawled corpse on the airport tarmac. That that airport has borne Aquino’s name since December 1987 (through a law that was enacted without the approval of his widow, the president at that time) is a continuing reminder of that ultimate responsibility. That is why President Marcos Jr. couldn’t even say the airport’s full name; his father and his family are implicated every time the name is invoked.

The Marcoses have apparently forgiven the late president Fidel Ramos for his crucial role in their ouster; they have not only forgiven their father’s defense secretary, Juan Ponce Enrile, for defecting from the Marcos regime, they have welcomed him into the official family as chief presidential legal counsel. The truth is that many of those who made the EDSA revolution happen have found ways to work with the Marcoses when they returned to political office. In that sense, EDSA as historical event is easier for the Marcos family to live with, or live down. But the Aquinos are a different matter.

Ninoy Aquino and his ragtag Lakas ng Bayan party had humiliated Imelda Marcos during the 1978 Interim Batasang Pambansa elections. Aquino had repeatedly rejected Imelda’s many warnings about not coming home. He could have stayed in comfortable exile in the United States, but decided (exactly like Jose Rizal) to return home to almost certain death. That decision led to the collapse of the Marcos regime, and cemented Marcos’ historical reputation, not as the enlightened strongman he believed he was, but as the brutal dictator the assassination revealed him to be.

To rehabilitate Marcos’s name and legacy, Aquino’s role in history must be degraded and denied.

Opposition opportunity

It is instructive to remember that when rumors of Aquino’s impending return circulated in 1983, the Marcos-controlled press (in an amazing display of editorial synchronicity) began printing unflattering, previously published stories about the opposition leader. Aquino before his arrest in 1972 was an easy target: rich, glib, flashy young man on the make, surrounded by bodyguards. The stories showed a man of great privilege and even greater ambition.

The current campaign against him draws on this portrait – and then adds a layer of outright fabrication. The new script includes old allegations: that he was a communist (or even a founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines); that his absence during the Plaza Miranda bombing of 1971, which was aimed at his fellow Liberal Party members, proved that he was behind the act of terrorism; that he had been naturalized as a Malaysian citizen, and so on.

But like Rizal, we remember Aquino because of the last 10 years of his life: seven years in prison and three years in exile changed him, we might even say purified him, and prepared him to be, in the final moment of his life, a hero.

I was at that massive funeral for Aquino on August 31, 1983 – 10 years ago on Wednesday. I was one of maybe two million, maybe even three million, who escorted him to his grave. It was the largest funeral in Philippine history, and one of the largest in the world. I was also at EDSA in February 1986, when as many as four million Filipinos thronged the streets. And I was one of the 16.6 million who voted for the 1987 Constitution: an astonishing 77% of all votes cast. I believed then, and I believe now, that all those millions saw Aquino’s sacrifice as a martyrdom, and Aquino as a hero.

The bracing thing: Lots of proof exist that Filipinos see Aquino as a hero. Many of the millions who turned out for his funeral or flocked to EDSA and other urban centers elsewhere in the country are still alive; many archives are accessible and easy to use.

In other words, the question whether Aquino is a hero, which Marcos and Duterte allies have seeded, is actually a contest that the political opposition should join willingly, because it is winnable. In its present state, the opposition is defensive by default. The war to define Aquino’s heroic legacy, centered on the principle that the Filipino is worth dying for, is an opportunity to go on the offense, to convert hearts and minds, to speak truth with power. – Rappler.com

Veteran journalist John Nery is a Rappler columnist, editorial consultant, and program host. “In the Public Square” airs on Rappler social media platforms every Wednesday at 8 pm.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] A Freedom Week joke](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/20240614-Filipino-Week-joke-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] Hitting rock bottom](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/Newspoint-hitting-rock-bottom-December-2-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=283px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] The Ninoy constituency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/TL-Ninoy-constituency-August-25-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=334px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.