SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] A civilizational conflict](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/07/TL-civilizational-conflict-July-14-2023.jpg)

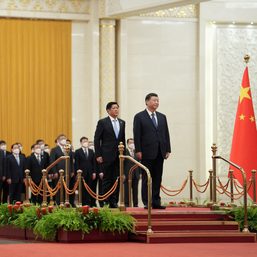

It needs to be recognized that the South China Sea issue has evolved not only from being a territorial and maritime dispute, nor even as a geopolitical contest between China and the United States, but as a civilizational conflict between those who share China’s cultural and ideological hegemony and those influenced by an international rules-based order.

China’s belligerent protest against the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), treating it merely as a piece of paper that is “null and void and has no binding force,” is a naked challenge to the architectonic structure of laws and systems that have grown out of the struggles for territorial borders and self-determination in international relations.

This system originated mainly from the history of the West.

Official Chinese statements made clear that “China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea shall under no circumstances be affected by those awards.” Xi Jinping has in fact thrown the gauntlet. He dared to rival the “Free World” by declaring his vision of an alternative world order, described as a ‘sea change’ in global diplomacy – his Global “Xivilization” Initiative.

Along with his reinvention of the old Silk Road and his aggressive inroads into the economies of pliable states, Xi now seeks to lead the charge towards dismantling internationally-agreed rules such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and its legal offshoots like the PCA ruling.

What accounts for this thrusting towards global power and cultural influence?

Century of humiliation

One possible reason, besides its obvious economic interests, is that China is still smarting from its century of humiliation in the hands of western powers.

A student from Mainland China tells me that since grade school, China has drummed into his generation’s ears that they should study well and beat the West in every possible way. It riles their gut that the Arbitration Court in the Hague has ruled that there is no legal basis for claiming “historic rights” over vast swathes of the South China Sea. Once again, their long memory counts this as another instance of historical injury inflicted by western hegemony.

Constructivist studies in strategic security have resurfaced the importance of beliefs and values that shape the psychological environment of a people.

In contrast to realpolitik approaches that put emphasis merely on economic forces and military hardware, this line of thinking revisits the effect of ideas on national policy. It shows how deeply-rooted concepts of how the world works can determine how a society’s leadership and its institutions are likely to behave when faced with strategic choices.

As China rises, for instance, we see the re-surfacing of its ancient self-image as “zhong guo,” – the “middle kingdom” or “central state.” China once saw itself as a benevolent ruler, not just of a country, but of an entire civilization.

The Chinese, it is said, think in terms of “tien hsia’ (tian xia), – ‘the world’ – that is, China was the world, or all that mattered. This is embedded in its language: in Chinese, we are told by linguistic experts, “world” and “empire” – “tien-hsia” – ‘all that is under Heaven’ – are synonymous terms.

This Middle Kingdom syndrome – the ethnocentric sense that it is at the center of the world – is an ideological construct based on a myth created during the Zhou period that the Central States, whose ruler held a Mandate from Heaven, has a civilizing influence that is to be extended to all the world. Since then, this has been at the core of Chinese self-identity, and continues to animate even the Chinese Communist Party, whose modern version of it is its mission to spread globally its brand of ‘socialism with Chinese Characteristics.’

In spite of having taken its place among modern developed nations, says a strategic analyst, “China continues to seek guidance from a past characterized by Confucian notions of hierarchical political order and a ‘moral geography’ that places China at the center of the civilized world.”

Similarly, this country at first behaved according to its traditional instinct for accommodation, even as it also shows acquired impulses originating from having gone through a deep and centuries-long experience of westernization.

Cultural divide

The debate over what to do with the South China Sea issue has opened up the deeper fissures in this society that lie hidden to outside observers. There is a very deep cultural divide that shows up between those who have been thoroughly laundered into western ways of thinking and doing and those whose universe of discourse and mental models continue to be framed within the native culture’s meaning system.

The former move within the larger orbit of a modern conceptual environment that shares the highly-developed language of the West for ‘rights’ and ‘rule-based’ approaches to ordering society. The latter operate within a more traditional code, preferring a more fluid and relational social exchange, where the lines tend to blur between the formal and informal structures and the force of personal connections can overrun policy and protocols.

This divide is mirrored by the difference in responses of former heads of the Philippine government. The government of the late president Benigno Aquino III, faced with unabated Chinese harassment of Filipino fishermen in the West Philippine Sea despite negotiations, chose to explore as a recourse the legal remedies available within the UNCLOS, marshaling the country’s deep bench of international law experts.

The Duterte administration, on the other hand, chose to capitulate, banking on his supposed personal friendship with Xi Jinping, and preferring opaque, behind-the-scenes negotiations such as that voiced by a former Philippine maritime official: “Negotiating and seeking consensus…It’s the Asian way.”

Yet far from doing consensus-building as is the “Asian Way,” China has become the big bully in the neighborhood, like the insistence on bilateral agreements instead of a binding Code of Conduct, backed up by this veiled threat to this country and other claimant states from Foreign Minister Wang Yi: “In waters where there are overlapping maritime rights and interests, if one party goes for unilateral development, and the other party takes the same action, that might complicate the situation at seas, that might lead to tensions and as an end result nobody will be able to develop the resources.”

Nevertheless, as a small country with very little hard power at its disposal, the Philippines resorted to international arbitration, and to everyone’s surprise, won resoundingly.

China’s analysts bristled at this, embarrassed perhaps that so small a nation should dare to thwart its ascendancy in the region. They denounced the Philippine case brought to the PCA and its ruling as a “political provocation in cloak of law.”

But this is precisely the point behind the recourse to the rule of law, particularly in situations of power asymmetries. The Philippine’s case against China’s inordinate claim of a historic nine-dash line shows the equalizing power of a global order where there exists a system of stable, clear and rules-based way of settling claims and disputes among nations.

In mustering the legal means at our disposal, we not only asserted our own rights but pushed the frontiers of international maritime law and redrew the legal landscape governing the South China Sea.

As a movie title once put it, “Minsan isang gamu-gamo ang lumaban sa lawin.” – Rappler.com

Melba Padilla Maggay is president of the Institute for Studies in Asian Church and Culture.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.