SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

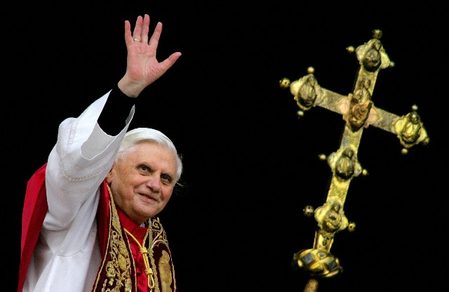

![[OPINION] Benedict XVI’s political theology](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/20230105-Pope-Benedict-Political-Theology.jpg)

When news on the death of Joseph Ratzinger, aka Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, broke out, commentaries, recollections, and analyses spread quickly all over social media. Western media has poised to conjure some spirits of the past and resurface assessments of a papacy that ended almost eight years ago.

Described by some if not most commentators as “conservative,” such a label is, for his critics, synonymous with both the person and its papacy. The New York Times has described him as the “unofficial figurehead of the conservative wing of the American church,” while Le Monde has used unreservedly the description “conservative theologian.” I, at some point, branded Ratzinger as one. I recall how my analysis, published in a journal article in 2008, considered his papacy as a factor that withheld the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) from issuing a firmer position against the administration of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (GMA) in 2005 and 2006.

It can be remembered that a few months after Benedict XVI’s assumption into the papacy, the Philippine Church was placed in a dilemma of whether or not it should support the call from some sectors for GMA to resign. After its plenary assembly, the bishops, led by its former president Fernando Capalla of Davao, issued a statement that the CBCP would not support any calls for the president to resign. In its 2006 pastoral letter titled “Renewing Our Public Life Through Moral Values,” the bishops cited Benedict XVI’s Deus Caritas Est (DCE), the newly elected pope’s first encyclical on charity. I remember how Mrs. Arroyo’s media liaisons used the papal document to support the bishops’ perceived pro-administration position. Years later President Benigno Aquino III would get back at the bishops in a speech delivered before Pope Francis no less.

But in retrospect many readers of the encyclical were selective, and some commentators, especially those who didn’t receive it quite well, were too colored by their pre-existing notions of Joseph Ratzinger as former prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In its own right, DCE actually gave us a fresh look at the Church’s mission and its vocation to social justice. Benedict XVI admits in paragraph 27 that “the Church’s leadership was slow to realize that the issue of the just structuring of society needed to be approached in a new way.” He’s not shy in mentioning, without necessarily agreeing, the Marxist criticism of the Church’s charitable activity which are “in effect a way for the rich to shirk their obligation to work for justice.”

Benedict reminds Catholics that “[a] just society must be the achievement of politics, not of the Church.” But this is not the entire message. To cut the statement would simply and surely yield a reading of him as conservative. The next line reveals the depth of his position on “Church and politics”: “the promotion of justice through efforts to bring about openness of mind and will to the demands of the common good is something which concerns the Church deeply.” Although he did not prescribe the specific “act” that must be used to fight for justice nevertheless it cannot be denied that he is of the belief that no Christian can run away from his duty to work for the good of all.

As a theologian who devoted his study to the works of Saint Augustine, Ratzinger would love to quote a line from the Church Father’s City of God: “a State which is not governed according to justice would be just a bunch of thieves.” He cited this in his first encyclical DCE and, again, in his address to the German Bundestag. Ratzinger then had had his own theology of politics, a position that he maintained even before he would become Benedict XVI. One can find this in his published debate with the philosopher Jurgen Habermas, Dialectics of Secularization, and the book published in 1991, A Turning Point for Europe?

His view affirms the importance of politics despite its fallen nature. For him it is a human necessity whose intrinsic criterion is justice. But he also believes that where politics promises too much, it becomes evil. He was of a strong philosophical position that at the deepest level faith cannot but intersect with politics, and theology should say something on justice. However, the question is not on the themes of “faith” and “justice” per se but of the ontology that precedes whatever interpretation that a theologian or a believer would take on God’s involvement in the world.

He would argue that the Church and its theologians cannot just naively talk about justice disconnected from “hope” and “charity.” It is wrong to say that because of Ratzinger’s conservatism the Church turns a blind eye to the injustices that have become globalized. On the contrary, his other encyclical Caritas in Veritate is more pronounced in condemning the dehumanizing effects of globalization and the neoliberal market.

In hindsight, my analysis of Benedict’s conservatism in 2005 was a product of the limitations of the time and of my readings. I am not shy in admitting that such a view was rather one-sided. “Conservative” has become quite convenient a label for the Pope Emeritus, and just like with anybody we would love to criticize, mental shortcuts are always preferable and comfortable. However, like the typical name-calling of the enemy we invent, it is not only lazy but also fails to consider the other side of things and their context.

For a pope and theologian who has written extensively and whose views have had to address various layers and shades of human experience, being judged “conservative” without qualification at the very least is not only unfair but also prejudicial. In the academic world, a way of giving due respect to one’s intellectual adversaries is by reading their work. No serious critique or literary deconstruction is possible without having first gone through the details of the text and more so its context.

Some theologians would contrast Ratzinger’s theology as the anti-thesis to the political theologies of Johann Baptist Metz and Leonardo Boff. But if political theology is first a theology before it is anything political, as it is a reflection and a spiritual exploration of how one’s faith in a living God can change the way we arrange our political structures and socio-economic relations, then Ratzinger surely has his own political theology that poses a serious invitation to all Christians. What he said in Introduction to Christianity deserves to be highlighted as our concluding words:

“The goal of the Christian is not private bliss but the whole. He believes in Christ, and for that reason he believes in the future of the world, not just his own future. He knows that this future is more than he himself can create.” – Rappler.com

The writer is director of human resource of the Sacred Heart School-Ateneo de Cebu, where he teaches Introduction to World Religions and Philosophy of the Human Person. He is also editor-in-chief of the PHAVISMINDA Journal of Philosophy. He has written two articles on Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI for said journal.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Wide Shot] Peace be with China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/wideshot-wps-catholic-church.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=311px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] A critique of the CBCP pastoral statement on divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-cbcp-divorce-statement-july-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=285px%2C0px%2C722px%2C720px)

![[The Wide Shot] Was CBCP ‘weak’ in its statement on the divorce bill?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/cbcp-divorce-weak-statement.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=258px%2C0px%2C719px%2C720px)

![[REFLECTION] Mary, Mother of the West Philippine Sea](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/may-mother-west-ph-sea-july-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=293px%2C0px%2C751px%2C750px)

![[OPINION] Ignorance and prejudice](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-ignorance-and-prejujdice.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.