SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

EXCLUSIVE: Marwan’s ties that bind: Aljebir Adzhar aka Embel

EXCLUSIVE: Marwan’s ties that bind: Ren-Ren Dongon

EXCLUSIVE: Marwan’s ties that bind: From family to global terrorism

Let’s start with a basic fact: the US has been actively involved in counterterrorism operations in the Philippines for at least 13 years. When the US special forces operatives landed in Zamboanga City in January 2002, I was on the tarmac chasing the soldiers as they got off the plane. When I asked them what they were doing, their answer was identical – and has remained that way over the years: “We’re here to train, advise and assist Philippine forces.” There’s a reason why.

Rappler looks at how US forces and resources have been used in counterterrorism operations in the Philippines within a global context. We speak with Filipino and American operatives and officials and look at examples of past operations to see the protocols in place for cooperation between the two countries. Many of those we spoke with asked for anonymity given the sensitive nature of the operations they were part of.

A day after the deaths of the 44 police Special Action Forces (SAF) operatives in Mamasapano was announced, I spoke with a former US special forces soldier who worked in the Philippines.

Explaining why the Americans could not be “boots on the ground,” the former Special Forces soldier said: “We’re allowed to provide support, intelligence, command and control support, mentoring, but we can’t be involved in direct action. I can tell you I never once witnessed something where American forces were conducting direct action. Some of us wished the Abu Sayyaf would engage us directly, but they would intentionally not attack us when they saw our Humvees on a patrol with the AFP (Armed Forces of the Philippines) because they know that if they shot at us, it was done! We would call in a quick reaction force, and we would’ve killed them.”

This partnership dates back to the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty. A former colony of the United States, the Philippines has an ambivalent attitude towards “Big Brother,” often fluctuating between love and hate.

In 1991, the Philippine Senate voted 12-11 to revoke the Military Bases Agreement between the two countries, closing down Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Force Base.

Reality check

The reality, though, is that Philippine security forces are one of the weakest in Southeast Asia, and Philippine officials have long turned to Washington for training and equipment as well as for support in conflicts like the South China Sea (what the Philippines calls the West Philippine Sea).

In 1995, partly because China built structures on Mischief Reef, Philippine President Fidel Ramos invited US forces back. Three years later, both countries signed the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), a controversial deal fought by the Catholic Church, leftist politicians and some members of the academe and civil society. It was ratified by the Philippine Senate in 1999. That agreement prevents the US from establishing a permanent base of operations in the Philippines and stipulates that US troops take a non-combat role – that they are in the Philippines “to train, advise and assist.”

In 2002, President Gloria Arroyo signed a Military Logistics and Support Agreement (MLSA), loosening the VFA terms. Now the US can use the Philippines as a supply base for military operations, and US special forces were deployed to help Philippine troops with counterterrorism operations.

In the next decade, the US military, the FBI and the CIA would begin training programs with their Filipino counterparts.

“The American forces love working with the Filipinos,” another former US special forces soldier said. “We are as good friends, allies, as it gets, and we can really help them. They do so much with so little.”

A Filipino officer said in an interview with Rappler, “We would be nowhere without them. You know we even have to count our bullets? So we can’t even do target practice if they weren’t here. Talking to them, working with them, training with them – all this helps us.”

A former commander of the US forces explained that training must go hand in hand with Philippine military-wide reform, as he cited sub-par or non-existent supplies because of a combination of corruption and inefficient processes.

“You know that the soldiers feel better going into conflict knowing that one of our choppers can medi-vac them out if they get shot. Some soldiers die bleeding after they’re shot because they can’t get help,” he said. “Look at the doctors with the troops. You know, there was a time when the doctor assigned to the fighting units was a dermatologist?”

In April, 2014 under President Benigno Aquino III, the Philippines and the US signed a framework agreement for EDCA or the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which allows increased US presence on a non-permanent basis and gives US troops greater access to Philippine military bases.

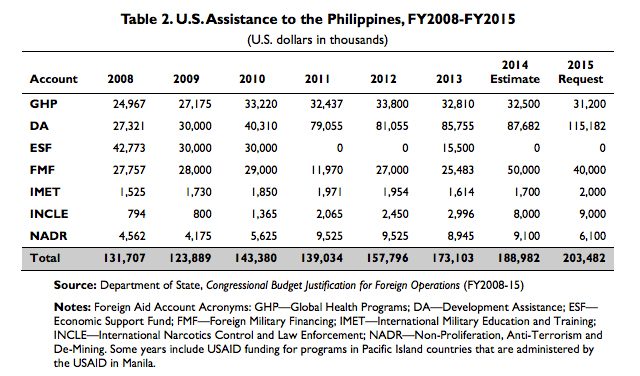

The Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, FY2014, said: “Security assistance supports the Administration’s strategic rebalance toward Asia by helping the Philippines become a more capable partner in promoting regional security.” Again, partly because of tensions with China, the Obama administration planned to nearly double Foreign Military Financing (FMF) in 2014.

Of course, there were tensions between the Philippines and the United States.

On the part of the Filipinos, there was friction when sometimes competing interests inside US agencies worked at cross-purposes, as the FBI and CIA did in the earlier years.

Over time, however, as workflows stabilized and parameters became clearer, that became better, according to officials familiar with the evolving partnership. There were also differences in priorities of threat assessments – with the Philippines long considering the communist threat its top priority while the Americans were prioritizing Islamist terrorism.

There were other issues. At one point between 2008 and 2013, the US Congress placed restrictions on about $2 million-$3 million of Foreign Military Financing (FMF) annually because of extra-judicial killings by the Philippine military.

Delivery of smart bombs

Between 2002 and 2013, the US gave the Philippines a total of $312 million in military assistance as well as military equipment, including smart bombs or Precision Guided Munitions (PGMs).

In the chart above from the Security Assistance Monitor, you can see the spike in arms sales from 2009 to 2010, when the US approved the delivery of at least 22 smart bombs to the Philippines.

In mid-2010, Washington pledged $18.4 million of precision-guided missiles funded under a US Congressional Act, which allowed its defense department to train and equip foreign military allies.

A classified document from the Philippines is explicit: “Fiscal year 2010 assistance for the Philippines provides a precision-guided missile capability to assist Philippine Armed Forces’ counterterrorism efforts in southern regions to combat the activities of the Jemaah Islamiyah and Abu Sayyaf Group.”

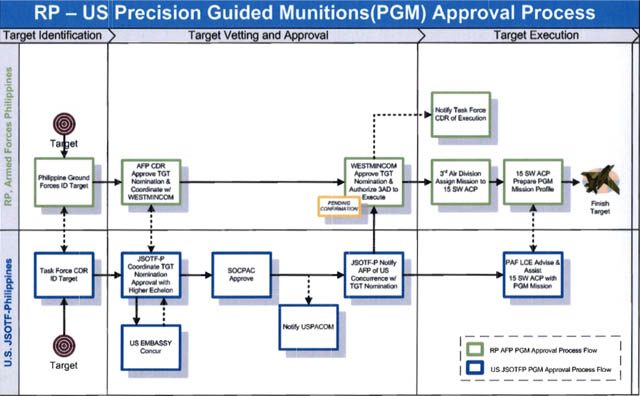

In February, 2012, the Philippines, working with the US, launched its first smart bomb attack targeting Malaysian Zulkifli bin Hir, better known as Marwan. (READ: Marwan and the ties that bind). While that attack failed, the classified chart below shows the meticulous planning and coordination between two separate countries and teams of special forces operatives.

In order to launch a smart bomb in the Philippines, the commanders and leaders of the two countries decided that it would take two keys to actually launch a bomb against a target.

From a high of nearly 2,000 US special forces in 2003 to an average of about 500-600 troops since about 2005, the Joint Special Operations Task Force-Philippines or JSOTF-P worked in western Mindanao with their Filipino counterparts.

JSOTF-P states its mission, hammered out based on bilateral agreements, simply: “At the request of the Philippine Government, JSOTF-P works together with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to fight terrorism and deliver humanitarian assistance to the people of Mindanao. US forces are temporarily deployed to the Philippines in a strictly non-combat role to advise and assist the AFP, share information, and to conduct joint civil military operations.”

Many of these operations are classified, with 4 major counterterrorism objectives against terrorists and insurgents: deny sanctuary; deny mobility; deny access to resources; and separate the population from the terrorist.

Retired Col. David Maxwell, had 2 tours of duty in the Philippines, first as commander of 1st Batallion, 1st Special Forces group with JSOTF-P’s precursor, JTF-510, then later as the JSOTF-P commander. Maxwell is adamant in his email sent February 3, 2015: “The US does not control any operations conducted by Philippine forces.” Named “a son of Basilan” in his first tour of duty, Maxwell is now the Associate Director of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University and makes it clear he has no inside information about what happened with Marwan.

“All the advice and assistance cannot prevent every tragedy,” he adds, “Especially if the Philippine military and police do not coordinate operations.”

Role in Mamasapano

Was there US involvement in Mamasapano?

“At the request of the AFP, US service members serving in JSOTF-P responded to assist in the evacuation of casualties after the firefight in Maguindanao,” said Kurt Hoyer, US embassy spokesman and press attaché.

Still, if you look closely at provisions of the existing agreements and workflows between the two countries, the mechanisms are in place for, at the very least, intelligence gathering and command-and-control support. Another former US forces operative told me, “The PNP would not do it without the Americans.”

That’s bolstered by the admission of Philippine police officials that the proof that the covert operations achieved its goal, the cut-off finger of Marwan, bypassed Philippine police hierarchy and was instead given directly “to the FBI.”

What’s not as well-documented in US public records is the extent of American involvement in counterterrorism operations involving the Philippine police, which began with the Anti-Terrorism Assistance Program or ATAP then intensified after 2008.

Did the US control the Filipinos as some reports suggest? Both American and Filipino forces involved in past operations I’ve spoken with say they think that would be impossible: the Filipinos would never allow it; and the Americans would never ask.

If there’s one case the Americans would’ve wanted to control, it would’ve been Operation Daybreak, the rescue operations for American hostages Martin & Gracia Burnham in 2002. Later at the sidelines of a conference at West Point, I spoke for several hours with American operatives who criticized the operations which killed Martin Burnham. Their repeated refrain: “They wouldn’t listen to us.”

The covert operations in Mamasapano are particularly tricky.

“We have long tried to avoid any appearance of US involvement in any operation that could hinder the peace process with the MILF,” said Maxwell. The Moro Islamic Liberation Front or MILF ended 17 years of negotiations and signed a peace agreement with the Philippine government in 2014.

The peace process has been a long-term goal for both the Philippines and the United States. Analysts and officials from at least half a dozen countries I’ve spoken with say there’s no choice but peace because the Philippine police and military cannot win the war.

The incompetence of the Mamasapano operations sparked strident political rhetoric and demagoguery – all of which may doom the passage of the Bangsamoro Basic Law or BBL, the last part of the peace deal.

If that happens, the MILF central leadership will lose credibility and control over about 12,000 armed men in a part of the Philippines where governance and security are weak at best.

This could potentially create a power vacuum – an open invitation to more extremist and violent groups from the region and around the world. The greater danger is the devolution of the radical ideology that once powered al-Qaeda. Now loose on the Internet, it has become a social movement that has sparked attacks from Iraq and Syria to Boston to Paris. – Rappler.com

Maria A. Ressa is the author of Seeds of Terror: An Eyewitness Account of Al-Qaeda’s Newest Center of Operations in Southeast Asia and 10 Days, 10 Years: From Bin Laden to Facebook.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] Patricia Evangelista](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/unnamed-9-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=486px%2C0px%2C1333px%2C1333px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.