SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Healer, first do no harm](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/08/smoking-vaping-sq.jpg)

My father is living out the final years of his life in regret.

For as far back as I can remember, my tatay was already a smoker. In many ways, he was forced into it. In 1958, when he entered the Philippine Air Force, cigarettes were not only the norm, but were almost a requirement to survive the stressful demands of the organization. That started his lifelong addiction to cigarettes.

Tatay didn’t see smoking as bad for his health. At the prime of his life, the stick between his fingers became his status symbol as a man.

Today at 88, the incessant “smoker’s cough” hounds my tatay — with painful sounds of wheezing and crackling deep in the chest. He also developed complications such as partial blindness, increased blood pressure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He has grown ever-reliant on inhalers and medication. Name an illness and he’s more likely to have it than not. He once told me that had he known back then what he knows now, he wouldn’t have started smoking, or at least he would have tried harder to quit.

Seeing my father fail in his lifelong struggle against his addiction would become a deep, personal undercurrent running through my work in the anti-tobacco and pro-health advocacy, although it took me decades to become completely conscious of the health risks of tobacco use.

Cure over prevention

As a young medical student in the early 1980s, I knew smoking was a bad vice, but I didn’t understand just yet the frightening degree to which smoking could harm one’s health. In class, there were no in-depth discussions on tobacco, and smoking was just one of those boxes you ticked off when collecting a patient’s medical history.

Yet as early as 1964, the US Surgeon General’s report concluded that tobacco was a definite cause of lung cancer, among other respiratory conditions. It was an important milestone in tobacco control, but it hardly made waves here in the Philippines.

Looking back, tobacco should have been a central topic in our subject called Preventive Medicine. After all, the class was designed to teach young healers how to help their patients avoid illness in the first place, instead of waiting to get sick and then seek treatment. But the emphasis was on the cure rather than prevention.

It is only with the hindsight afforded by decades of clinical experience that I understand now why the medical community is so muted in its opposition to tobacco use: The sheer magnitude of smoking, in the Philippines and elsewhere in the world, coupled with the tobacco industry’s aggressive push for their products, may not be for the faint of heart.

Tobacco scourge

The 2015 Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) shows that almost 16 million Filipino adults are current tobacco users, around 13 million of whom smoke daily. That means an average daily consumption of as many as 11 sticks — more than half a pack. The high number of active smokers means that tens of millions of non-smokers are exposed to secondhand smoke, particularly at work, at home, and in public places like restaurants and bars.

This fact alone should be enough to trigger outrage among public health professionals, but what’s more worrying, based on the 2015 GATS report, is that daily smokers started young at an average age of 17.5 years, even before they should have been able to legally purchase cigarettes. Indeed, the 2015 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) that was conducted in the same year as the latest GATS (2015) found that nearly 15% of teens aged 13-15 years young were current smokers.

Both reports also hinted at another impending crisis – e-cigarettes had already entered the local market. The level of use was just shy of 3%, but a third of Filipino adults have heard about them. In particular, these new products seem to be more popular among young adults aged 15-24 years.

It’s been six years since both reports came out (with updates initially planned for 2020 until the COVID-19 pandemic struck), but it appears millions of Filipinos continue to be trapped helplessly in their tobacco addiction. With the rise of electronic alternatives, many more are bound to fall into this trap.

Since I was a medical student in the 1980s, our knowledge of the health risks of tobacco use has grown explosively. We know – conclusively, and with no shred of uncertainty – that some of the most debilitating and deadly chronic diseases trace back to it.

And yet, we as a community, save for a few, still haven’t put up a united front against tobacco. Some of the leading professional organizations in the country don’t even have a dedicated anti-smoking advocacy group.

As a doctor, I understand that it’s not our job to enact laws to protect public health. But it is our responsibility to advocate for our patients. So why haven’t we done so yet, especially with regard to tobacco use?

Industry intimidations

By the time I became the chairperson of the Philippine Pediatric Society’s Tobacco Control Advocacy Group in February 2017, vapes and e-cigarettes were being marketed as alternatives to cigarettes, in bright and attractive stalls in malls that children and teens frequented. In 2019, I saw these dangerous products — laced with nicotine and potentially addictive — already being sold in convenience stores, easily available to anyone who could afford them. Health warnings were almost unreadable, and there were no locks, no disclaimers, and nothing else by way of regulatory oversight other than a couple of store clerks who didn’t know any better.

Against this backdrop, the anti-tobacco movement in the Philippines is determined, but is dwarfed by corporations. We don’t have as much funding, nor do we have friends in high places. So in July 2019, I turned to social media. I put up a post on Facebook, which achieved a small degree of virality.

Before long, an industry representative sent me a friendly email. They wanted to speak with me in person and show that their vapes were safe and were a healthy alternative to cigarettes.

I didn’t buy it.

In a fellowship with the American Academy of Pediatrics, I learned all about the electrical circuits that powered these devices, the chemical make-up of the vape juices, and how these components all come together to replicate essentially the same cycle of addiction that cigarettes elicit. That episode taught me how insidious the industry was, how dogged they were at pushing their propaganda.

In August 2019, barely a month after my Facebook post, the hospital I was affiliated with received an invitation to a “medical symposium” sponsored by one of the big e-cigarette companies. It came with all the trappings: big names in the industry, free accommodations to an upscale hotel at the cosmopolitan Bonifacio Global City, and thousands of pesos in honoraria.

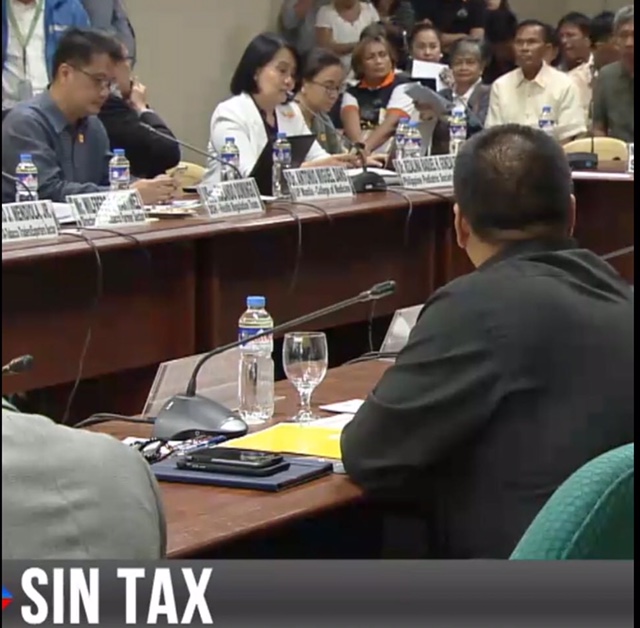

I would soon learn that the industry had its tendrils in the government, too. A few months after the sham symposium, the Senate held a hearing about a proposed bill regulating e-cigarettes. The pro-health and anti-tobacco advocates, many of whom were doctors, were seated far off to the side, tucked in a corner away from the main floor.

In stark contrast, industry representatives, dressed in slick suits and carrying around their product samples, were right smack in the middle of the action, personally mingling with our lawmakers during breaks in the session.

Over the years, since I became more vocal and involved in the pro-health lobby, I’ve learned to thicken my skin in order to cope with the industry’s aggression. Just a year ago, a Congressional representative, who had consistently backed industry-friendly bills and arguments, even accosted me publicly at a hearing, casting doubt on my medical expertise, before telling me that I should just keep quiet, or I would be thrown out of the hall.

A long and difficult process

Whenever I speak to other doctors about my advocacy, I inevitably get told something along the lines of, “Maganda yan, Riz, kaso mahirap.” (That’s great, Riz, but that’s difficult.)

With all these challenges, it’s quite understandable that there hasn’t been a stronger outcry from the medical community. But as doctors, not only are we the most qualified to speak up about the hazards of smoking, we are also compelled by the oath attached to our license.

It behooves us to start reframing our understanding of medicine and pursue a more preventive approach rather than an over-reliance on treatment. It’s a long and difficult process of unlearning, but it’s something that I believe the medical community needs to go through.

Much of what we know about tobacco from the media — particularly these novel alternatives — is either incomplete or tainted with the industry’s manipulation. I encourage my colleagues to be skeptical about all of these health claims, and seek training, guidance, or even just advice from professionals in the field whose credentials they trust.

But most importantly, I think we need to revisit the fundamental reason we chose to become healers in the first place, and to reorient ourselves with our ethical promises. Monetary rewards shouldn’t be our main motivation. We are dealing with lives, after all. Not stocks, not products, but lives.

As an important rite of passage into becoming doctors, we make the pledge to first, do no harm. Above all else, this is a pledge of humility: that we be honest enough to admit when we lack knowledge and experience on a certain subject to provide counsel to our patients.

As the tobacco industry continues to blur the line between what is safe and what is not, and undermines the authority of the medical community, there has never been a more crucial time for us doctors to hold fast to our oath. – Rappler.com

Dr. Rizalina Gonzalez has been an anti-smoking advocate since 2012, when she became the president of the Southern Tagalog Chapter of the Philippine Pediatric Society (PPS). Currently, she is the chairperson of PPS’s Tobacco Control Advocacy Group and is an international fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Tristan Mañalac is a freelance journalist focusing on health, the environment, and science. His work has appeared on various local news outlets, and he writes regularly for a medical trade magazine with an Asia-Pacific circulation.

This article is produced under the Nagbabagang Kuwento (Burning Stories) Tobacco Control Media Program of the Probe Media Foundation, Inc., which is supported by the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Tobacco, vape groups are bullying public health advocates in a pandemic](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/07/imho-tobacco-bully-1280.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[Free to Disagree] Sabwatan ng mga doktor at drug companies](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-sabwatan-doktor-drug-companies-April-22-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=292px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.