SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Since 2020, I’ve been fixating on my viewing behavior, both as audience and critic, and hence began to keep track of films I saw, sat through, and occasionally mulled over. I created lists and rankings with the goal of having a headstart towards interpreting this mountain of content in year-end essays such as this, until the task proved to be taxing. Letterboxd, or maybe this whole notion of canonizing, is partly to blame for it. But creating this year-end list, in some ways, also means holding oneself accountable — for critics to dissect what remains undissected, to interrogate the ideas they promote, and to examine how film and film writing can counter or enable the status quo.

Cinema, after all, does not exist in a vacuum. This year sharply reminds us of that. While many releases fruitfully broke through the noise, led by the Barbenheimer hype, 2023 also saw historic strikes by the SAG-AFTRA union and the Writers Guild of America due to long-standing labor issues, effectively putting Hollywood productions to a halt. The writers’ guild won an agreement with the big studios in late September. The actors’ guild, on the other hand, reached a tentative deal in early November.

Around the same time, the Palestine Film Institute, alongside many other filmmakers including Filipino director Miko Revereza, pulled their activities and films out of the International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) following the festival’s condemnation of the revolutionary slogan “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” carried by protesters during the opening night. This, despite a Dutch court ruling stating that the said slogan is protected speech and doesn’t promote antisemitism. The response was in light of the ongoing genocide in Gaza by the Israeli occupation, which began decades ago and has since killed thousands of innocent lives.

These cases demonstrate both the strengths and limits of cinema in times of heightened oppression. Programmer and filmmaker Aiko Masubuchi boldly articulated this in her ballot submitted to Screen Slate’s year-end list: “Nothing this year has made me see the world differently and changed me more profoundly than the images and sounds coming from the Palestinian resistance toward liberation. Free Palestine.” To put it simply, business as usual no longer remains a morally and politically sound course of action.

But while moviegoing and cinema at large remains a privilege, it can also harness stories that would otherwise be sidelined for many selfish reasons, hence this list. And thumbing through hundreds of titles released this year can be quite debilitating. There is a lot to keep up with across genres, forms, streaming sites, and countries — even for a person who does all this for a living.

And yet there are films that tower over the commonplace, those that exhibit narrative and filmic daring, and those that gesture toward endless possibilities in the years ahead and hence make a strong case for essential cinema.

Honorable mentions

Noteworthy local titles are the following: Joseph Mangat’s Divine Factory, which expertly sketches both the divinity and carnality of queer bodies against the scale of religion, as it observes and interacts with LGBTQ+ workers mass-producing religious figures in the outskirts of Manila; Lav Diaz’s Essential Truths of the Lake, another foray into the auteur’s relentless chronicling of our nation’s woeful history, now set in the thick of the Taal eruption and Duterte’s drug war; Stephen Lopez’s Hito, a QCinema crowd favorite that careens into a bleak future yet refuses to cave into the dystopia; Carl Papa’s Iti Mapukpukaw, the Philippines’ bet in this year’s Oscar race, whose complex and evocative storytelling propels local cinema forward; Khavn’s National Anarchist: Lino Brocka, an exultant mapping of Brocka’s cinema and politics that doubles as a deconstruction of Philippine cinema and society at large; and Apa Agbayani’s Somewhere All the Boys Are Birds, which intricately understands its form not a shortcut but as a pocket-sized tool of articulation that, in this case, negotiates with queer longing and futurity.

Internationally, there’s Khozy Rizal’s Basri & Salma in a Never-ending Comedy, which touches on familial and generational baggage through a gutsy visual grammar; Emma Seligman’s Bottoms whose unhinged, lowbrow humor is an absolute blast; Elizabeth Banks’ trippy and audacious tragicomedy Cocaine Bear; Giselle Lin’s I Look into the Mirror and Repeat to Myself, a graceful portrait of collective trauma and healing; the singularly breathtaking visions and visuals, particularly those rendered in utter silence in Pham Thien An’s Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell; Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things, buoyed by its colossal and truly transportive world-building, as well as its epic ensemble work, led by Emma Stone; and Todd Haynes’ taut and cunty interrogation of the clutches of method acting and celebrity culture in May December, steered by perfect acting.

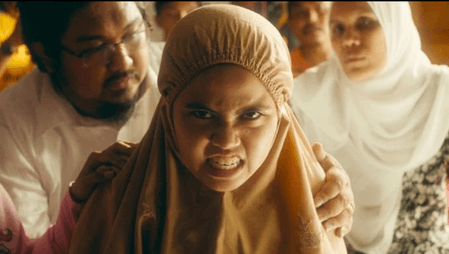

15. Tiger Stripes (dir. Amanda Nell Eu)

Written and directed by Amanda Nell Eu, this Cannes-winning feature debut is many things: a metaphysical coming of age, a mapping of tradition, a critique on environmental plunder, and a metaphor for transhood, all of which points to the shapeshifting beasts still lurking in present-day Malaysia, perhaps the chief reason why the Malaysian government censored the film. Tiger Stripes is loads of fun in the ways that it challenges the formality of body horror as a genre through its playful beat and off-kilter prosthetics, and how it doesn’t yield to the Western psyche in terms of narrative and vision.

14. Nowhere Near (dir. Miko Revereza)

Miko Revereza’s proclivity for double exposures, wayward visuals, and imperfect textures blends well with the ruminative soundscape of Nowhere Near, his latest (and perhaps his last) documentary on the immigrant experience — this cruel liminality that he has been interrogating for nearly three decades now. By browsing through census records, family photos, Google Maps, and locations fractured by history, Revereza comes in close contact with his personal, diasporic roots that eventually branches out to examining the futility of empire, colonial residues, the incoherence of memory and departure, and the limits of gaze. What Revereza achieves in this sober yet wounded retelling is hardly abstract, for it is the crossroad that countless immigrant lives remain to confront.

13. Passages (dir. Ira Sachs)

In a year of cinematic bisexuality and love triangles, Ira Sachs’ Passages is a sure-fire hit. Filmmaker Tomas (the ever-pulsating Franz Rogowski) begins a love affair with Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos), muddling his relationship with his husband Martin (Ben Whishaw), only to discover later on that he can’t commit to this very thing he willingly enters. Plenty of sexy and hot moments (that insane crop top, for one) occupy the film, but also loads of chaotic and narcissistic impulses, and the whole thing becomes so engrossing just for the wealth of feeling it evokes in every frame, unafraid to dwell in gray areas, in the wreckage. Sachs, in this career-best, makes us fall in love with a toxic, self-destructing, and deeply terrible creature but also offers us a caveat on dating filmmakers and the bitter pills we are forced to swallow in dysfunctional relationships.

12. Evil Does Not Exist (dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Evil does not exist, because we create and shape it, argues Ryusuke Hamaguchi in this latest work, which others might mistakenly tag as less ambitious or tame, considering the terrains explored in Drive My Car and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, but the film is far from that. Raw and introspective, Evil Does Not Exist looks wondrously into how a sense of belonging and care binds a community, especially the smallest ones, in the face of capitalist encroachment and corporate rapacity. What stands out here is Hamaguchi’s enrapturing attention to structure and dissection of scenes to really spin a great yarn, to articulate something so simple yet profound — with a stunning soundscape at that.

11. Of an Age (dir. Goran Stolevski)

Among this year’s overlooked films, Goran Stolevski’s Of an Age follows a frenetic story that begins with a 24-hour upending encounter between two people en route to separate futures. More than a study of queer awakening, the film turns into a full-throated exploration of aging, of the several lives that we have lived and thought to have outlived, only for it to come charging at us in moments we least expect it. Despite its crushing endnote, there is comfort in knowing that the film doesn’t limit itself by being cynical and hence embracing the complexity of this particular grief. What a thing of beauty.

10. All of Us Strangers (dir. Andrew Haigh)

All of Us Strangers is deceptively simple. Director Andrew Haigh, the genius behind Weekend and 45 Years, seduces us with a pitch about a romance specific to the queer experience, until he unleashes a tender yet world-crushing ghost story. At the center of which is screenwriter Adam (played by the magnetic Andrew Scott) who bargains with space and time to again encounter even for a brief, transitory moment all that he holds dear. Haigh intimates both absence and presence, and how it can cut across different junctures in our lives, articulating that grief only truly ends when we can no longer hold space for love. In this decimating tale, healing is a room with its door left ajar, forever cursed to be invaded by incomprehensible pain, without anticipation, beyond warning.

9. Fallen Leaves (dir. Aki Kaurismäki)

One of the funniest bits among all titles this year belongs to Fallen Leaves, Aki Kaurismäki’s latest work since 2017, when two of its characters, shortly after seeing Jim Jarmusch’s zombie comedy The Dead Don’t Die, say in the most deadpan delivery that the film reminds them of works by Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson. In many ways, Fallen Leaves steeps itself in this absurd, wry approach to buoy its central narrative, about a Helsinkian couple (Alma Pöysti and Jussi Vatanen, one of this year’s best duos) in search of love and happiness amid heightened scraping-by. The film makes for a perfect watch chiefly because it doesn’t overstay its welcome. Its 81-minute runtime feels so succinct and emotionally full, never yielding to unnecessary sidestepping.

8. Tumatawa, Umiiyak (dir. Che Tagyamon)

It dawns on me now, after writing a couple of reviews about the film, how Che Tagyamon’s Tumatawa, Umiiyak attends to the dignity of memory. Just when one reckons that Tagyamon fabricates a world through a prism of innocence, she immediately dispels that by interrogating how fickle and malleable memory can be, especially in the hands of state spin doctors, and how vantage points cement many structures that tower over us and our inner lives. Even when the film speaks about destruction, the images burn with life, suffused with depth and meaning. More than anything else, it perseveres against the capture of our imagination.

7. Past Lives (dir. Celine Song)

Parallel to Nowhere Near, albeit in an entirely different approach, Past Lives, Celine Song’s directorial debut, also makes sense of the immigrant experience, initially packaged as a romance story between two souls separated by geography but linked by a mystical contract, their so-called in-yeon. Much of the discussion orbiting the film fixates on its supposed lack of an overt, if not grander, conflict, but departure, especially in diasporic terms, isn’t always straightforward. This is what Past Lives exhibits so eloquently in how it renders the friction between its trio of characters in utter silence, in awkward pauses, in every tentative gaze. It’s a story about connections and the lack thereof, about how we compartmentalize parts of ourselves to tame all the years of ache, about the several lives we once had but can no longer inhabit.

6. Rye Lane (dir. Raine Allen Miller)

Leave it to Raine Allen Miller to craft one of the slickest and most daring romantic comedies as of late. The story pivots on the meet-cute between Dom and Yas (played by David Jonsson and Vivian Oparah, respectively, another perfect pair this year), 20-somethings still reeling from their respective heartbreaks and hence end up sharing a day in South London. How Miller concocted this feature directorial debut with a production design that makes every single frame pop and ooze with zip and excitement feels totally terrific. It crosses many lanes, without losing its overall direction, all within 82 minutes, which is a pretty cool feat.

5. The Breaking Ice (dir. Anthony Chen)

Whereas Perfect Days speaks about the mundanity of achieving happiness, Anthony Chen’s The Breaking Ice conveys the opposite, cracking open endless sorrows that simply can’t be explained. We journey with three “sad hot people,” to borrow the words of IndieWire’s David Ehrlich, whose lives are caught in a moment of freeze. The entire thing works because of how Chen renders the film’s landscape parallel to the hollow spaces that inhabit its characters, this profound immobility they all share. Like Perfect Days, its endnote also packs an emotional punch, thick with hope and warmth, despite everything.

4. Anatomy of a Fall (dir. Justine Triet)

Courthouse dramas and crime procedurals are usually not up my alley, for how too calculated and too mannered they could get, but Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall is a welcome surprise, precisely because it expands on the dictates of the genre, a marker of any great work. At the heart of the narrative is a German novelist (the volcanic Sandra Hüller) accused of killing her husband following an accidental (or intentional) fall. But what the film unravels later on is no longer the case at hand but the anatomy of reality, of truth, of memory, and how it can get so tricky, depending on who’s telling and who’s questioning. And when the verdict is finally handed down, we very well know that the damage has been done. Astute and precise, Anatomy of a Fall exhibits the formula for perfect storytelling.

3. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World (dir. Radu Jude)

You can expect everything about Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World yet you’ll still be left in awe of the towering heights that it is able to achieve in terms of narrative and filmic daring. Romanian visionary Radu Jude tours us around Bucharest through the film’s heroine Angela (the gripping Ilinca Manolache), an overworked and underpaid gofer hired by a multinational company to shoot a workplace safety video, only to unearth the opposite. At once deranged and sane, hilarious and depressing, sprawling and clinical, the film makes for a mordant critique of corporate exploitation, the depravity that internet culture molds, and the failures of many imposing systems we all participate in. Throughout its 164-minute runtime, this masterwork sucks us into its world like an all-consuming black hole — a world so familiar and has long been ending for many of us.

2. Perfect Days (dir. Wim Wenders)

Happiness does not have to be so spectacular. This seems to be the chief argument propelling Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days, which orbits around the quotidian life of Hirayama (played by Kōji Yakusho, who should be sweeping the Best Actor race this season), a middle-aged man who routinely cleans Tokyo’s toilets and prefers to keep to himself. In his leisure time there’s his favorite books and cassette collection. Then on most days there’s the quiet, the lingering stillness. What Wenders calibrates here, without ceding an inch on cheap emotion and romanticism, is nothing short of perfection. He tracks the most minute of details, the tiny pockets of ache, the many hows and whys that yield no definite answers with such grace and lyricism, until all the feelings wash over us, like watching the burning sky in the golden hour, and finally understanding what it takes to truly like ourselves and appreciate the gentle gestures of life, even on our rough days.

1. Woman Of… (dirs. Małgorzata Szumowska and Michał Englert)

So many of the films I’ve seen this year are titles that I’ve anticipated and marked in my personal watchlist, carefully picking out what to see first and to invest time in, save for one — this Golden Lion-nominated drama written and directed by Małgorzata Szumowska and Michał Englert. In fact, it was K, a filmmaker and dear friend, who urged me to check the film at this year’s QCinema. We sat next to each other during the screening in the company of no more than 15 people. And having no knowledge of Woman Of… prior to viewing it is no doubt the best decision I’ve made this year, at least in terms of viewing habits.

The story tracks the 45-year odyssey of transgender woman Aniela towards liberation, set against a post-communist Poland, with Malgorzata Hajewska-Krzysztofik sublimely taking on the central role. That the directors refuse to present Aniela’s life in its terminus but rather in its living, multiple terms, to loosely paraphrase K, is what pulls me into this masterwork. It’s a rarity these days to encounter a story of a trans woman that is not about the people around her and how they have come to accept her but simply about herself and her personhood, with all the joy and pain it carries.

I don’t have the exact word for it, except grace. Do you know what that means for someone who barrels through a world of erasure, who looks at her body still thinking about countless prying eyes, and whose transhood is not shaped by painless love? Absolutely everything. So, I took it all in. I let the tears run. I disappeared into the years. And I came out of the film understanding this part of me a little bit better and this tension between what is and where to. Woman Of… above all else points towards worlds beyond where trans people are not dead and whose existence is no longer radical, no longer reduced to corporeal cruelty. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.