SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

Filipino auteur Lav Diaz has never been afraid to take on gargantuan thematic preoccupations: from the Philippines’ colonial history, to state-sanctioned violence, down to the Marcosian reign of terror that continues to seep into contemporary Filipino lives. In every Diaz work, cruelty grows like a contagious disease awaiting its next host. And when it festers, characters gently descend into madness, if not oblivion, at times in different forms but wretched and damaging all the same, forcing all possible routes to arrive at a dead end.

And it often takes a while before one could reach the right frame of mind to comprehend every point of discussion that Diaz is bent on interrogating film after film, over hours after hours of footage, confirming the multitudes and clarity of his vision. But what towers over his cinema is how he always thinks in historical terms, the very anchor that holds his films together to form a lengthy yet refined whole.

The same impulse informs one of Diaz’s latest epics, Isang Salaysay ng Karahasang Pilipino (A Tale of Filipino Violence), which debuted at Festival International du Cinéma Marseille in July 2022. In an interview, Diaz says that he created the “film-novel” out of his first-ever television series Servando Magdamag, which is based on a short story of the same title written by National Artist Ricky Lee, and slated for ABS-CBN streaming platform iWantTFC.

Clocking in at nearly seven hours, Karahasang Pilipino chronicles the sorrowful life of Servando “Bandong” Monzon VI (John Lloyd Cruz), who is set to inherit his clan’s power and fortune — and with it his family’s history of violence — given the impending demise of his despotic grandfather Servando Tres (Bart Guingona), who has long enjoyed impunity for his crimes, all of which are settled under the table.

However, things take a significant turn as the Marcos regime, enlivened by its thirst for blood and desire to control, begins to seize the Monzon hacienda. This puts Bandong at a crossroads, exacerbated by the affiliation of his pregnant wife Belinda (Hazel Orencio) and brother-in-law Delio (Gio Gahol) with the revolutionaries, all while he’s trying to protect their farmers and plantation workers, handle the mental condition of his Tiya Dencia (Agot Isidro), and play with the devil, Captain Leon Andres (Earl Ignacio), who is leading a military unit inside the Monzon farms.

Reminiscent of Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon, also a recent work by Diaz, Karahasang Pilipino interweaves two parallel stories, that of Bandong and his long-lost twin brother Hector Maniquiz (also played by Cruz), a madman who persecuted and killed his father Aris (Dido dela Paz) after allowing the abuse of his mother Helen (Charo Santos-Concio) at the hands of a cult leader they once worshiped.

Cruz, who has now made five features with Diaz, creates a twistedly disarming character out of Hector, allowing himself to disappear into the role and be consumed alive by Hector’s proclivity for destruction, like maggots feasting on one’s flesh, so much so that he doesn’t bat an eye after murdering the believers of their cult in broad daylight.

From Fabian in Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan to Primo in Alon, the likes of Hector are seemingly part and parcel of Diaz’s relentless probing of the Philippines’ impaired psyche and historical memory, finding a fitting metaphor in them for the network of impunity that has long kept the weak and poor unprotected and the powerful and rich untouchable, thus providing magnitude to the film’s title.

But in Karahasang Pilipino, Diaz also incorporates other interesting characters, such as a philosopher (Nanding Josef), the young pious leader Kristo (Reynan Abcede), and a blind group (Glendel Dacumos, Jo-Ann Requiestas, and Lhorvie Nuevo) to ruminate on the country’s complex relationship with truth and religion, and how such forces help facilitate horrible acts, whose harsh consequences are often buried and set aside, especially by those who are more than willing to look the other way.

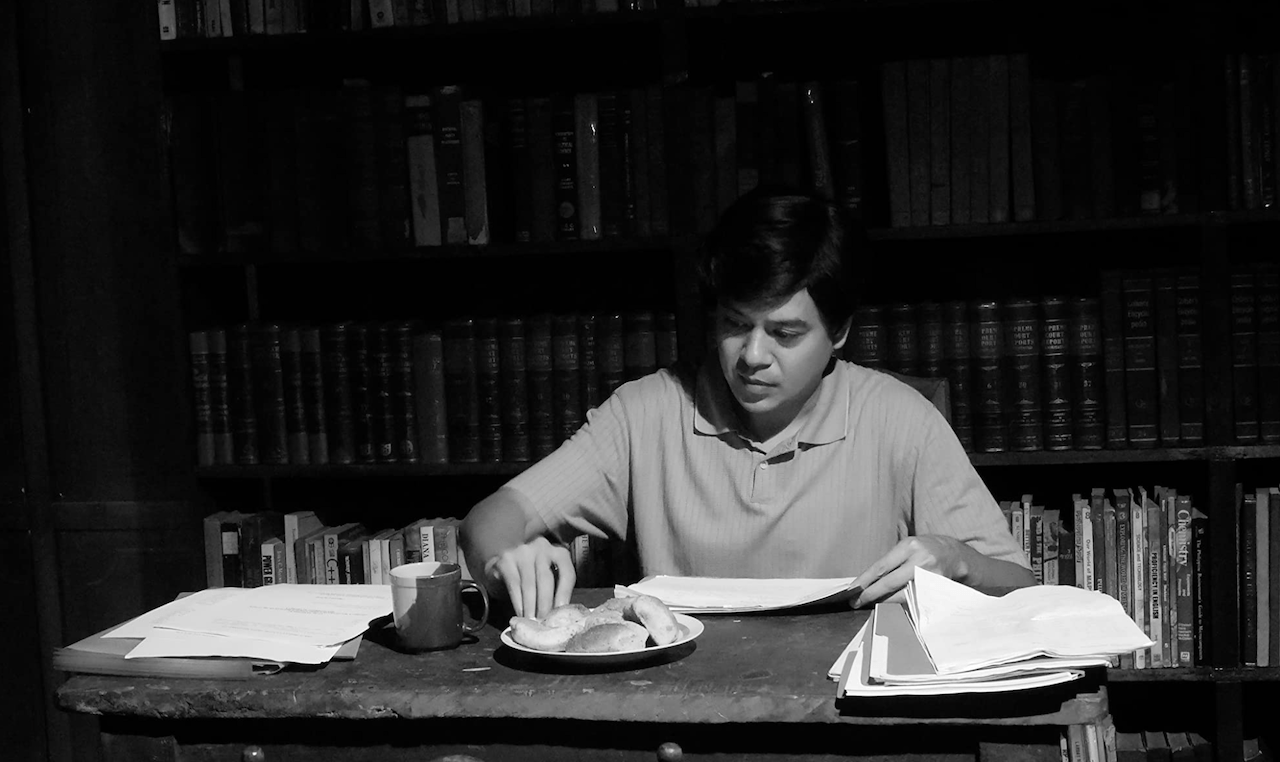

Working with cinematographer Daniel Uy, who also shot Diaz’s Ang Hupa, the director again goes for his signature monochromatic world, static long shots (most of which are sharpest during night scenes), carefully constructed framing, and recurring images of water and the forest. All of these demonstrate Diaz’s keenness to observe and ability to use the passage of time in examining the deeper trenches of the human condition. In this way, Karahasang Pilipino expands on its source, both in length and narrative scale, expertly creating an ouroboros of a nation that keeps finding itself in the same sorry state that it vows to eradicate, as though God has finally turned his back on it. “God sees the truth, but in the meantime, he wanders first,” says Bandong’s close pal Luke (Erwin Romulo).

However, one, especially a seasoned viewer of Diaz’s cinema, cannot help but ask why the filmmaker is so keen on depicting people of authority as central subjects in his films, even as he explores occasional departures — pursuing plot points that can hold water on their own, injecting dream sequences, and letting an image last longer than it should to highlight details that often go unnoticed yet are pivotal to the narrative. The duration of the film alone allows one to come up with several answers, but all of it boils down to this sense of urgency, that characters like Bandong are necessary to interrogate how power, magnified by a culture of neglect and more power, can erode many lives and command a nation’s fate, and Diaz knows better than to leave stones unturned, to leave such a social position unexamined, slowly and patiently parsing every possible nuance.

Inherently tied to the story of Bandong, a child of privilege and nepotism and buoyed by his bourgeois inclinations, are the stories of the likes of Belinda and Delio, who belong to the masses and, on such an account, squarely understand what it means to fight for their rights, endure the brutality it entails, and desperately cling onto hope (because without hope they would have nothing) — the very reason why Diaz creates the stories he keeps creating. Gahol’s Delio, in one of his monologues about the nation’s woeful past and the plight of the working class, leaves the audience to relish his quiet intensity and firmness that his truth would never waver, and he holds this conviction even at the expense of his own life, echoing the cycles of violence the state has long perpetuated and the terrible reality of those living on the fringes.

Throughout the film, there’s an image that Bandong recurrently dreams of: an obscured figure of a man watching a home set on fire. Inside it, a family is getting burned alive, desperately crying for help but to no avail. The man can do nothing but listen to the sounds of pain. “It keeps repeating in my dreams. It seems like a never-ending nightmare,” says Bandong.

This image captures the menacing darkness that looms over the film, the same darkness that will direct Bandong to pull the trigger, for he cannot escape his history. So it’s difficult to see the film as another cautionary tale, precisely because we have seen the caveats and forebodings before yet choose to ignore it, because despite our noble efforts, we still find ourselves at the behest of the dictator’s son. But this brings to mind some wise words from a dear friend: “In the struggle for national liberation, there are no lesser ways, only greater ways.”

In this morally gray area that Karahasang Pilipino operates in, violence is present at every turn and only awaits the ripening of conditions before it reduces everything to dust. And we endure it, as if we’re watching the cruelty in the dark, behind a curtain, carefully measuring our breathing, praying that the gun will never find us. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Only IN Hollywood] As his films go to Rome, Marseille, Lav Diaz makes 1st TV series as writer-director](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/07/lav-diaz.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[Only IN Hollywood] ‘Kinds of Kindness’ cast, Lanthimos on their ‘bizarre, special’ film](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/KindsofKindness-Emma-Stone-Yorgos-Lanthimos-and-Jesse-Plemons-at-the-New-York-premiere-of-Kinds-of-Kindness-Searchlight-Pictures11.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=238px%2C0px%2C853px%2C853px)

![[Only IN Hollywood] Producer Alemberg Ang reveals details on Isabel Sandoval’s ‘Moonglow,’ other projects](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/AlembergAng-Alemberg-Ang-Isabel-Sandoval-and-Arjo-Atayde-on-set-of-their-Moonglow-set-in-the-60s-and-70s.-Contributed-Photo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Only IN Hollywood] Kevin Costner’s big financial gamble to make not one but four ‘Horizon’ films](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/kevin-costner-standing-ovation.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=187px%2C0px%2C853px%2C853px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.