SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In a perfect world, a list like this would be much longer. This particular selection below – of films released under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, criticizing or responding to his human rights abuses and authoritarian style of governance – is by no means exhaustive. But it’s still telling how few of these kinds of movies have been allowed to be funded or shown to the general public over the last 5 years.

This only reminds us what has always been abundantly clear: that much of the Filipino film industry is still so incredibly cordial with the very government it should be holding accountable. Producers continue to hire incumbent politicians or prominent members of political families to star in their movies. Meanwhile some festival organizers, and government agencies like the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (or MTRCB), continue to have the power to potentially censor films with more subversive content.

Just last year, Joselito Altarejos’s Walang Kasarian ang Digmang Bayan was removed from Sinag Maynila’s festival lineup at the last minute. The festival, founded by director and Duterte ally Brillante Mendoza, reasoned that it was disqualified due to the finished film’s deviations from its initial screenplay. However, it’s impossible to ignore just how brazenly critical of the government the film was supposedly going to be, making its disqualification all the more infuriating.

The films below, which did manage to get into cinemas or onto locally available streaming services, have much to teach us. Some of them act as essential voices of dissent in an industry that has largely lost its courage to protest. Others remind us of the limits of our industry that we still need to overcome—if we truly want our cinema to become a cinema for the people, and not exclusively for the elite.

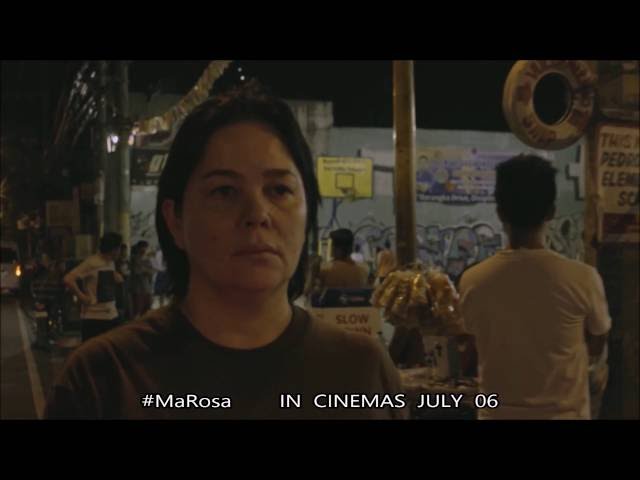

Ma’ Rosa (directed by Brillante Mendoza, 2016)

Ironically, the first high-profile film to be released under the Duterte administration about police operations against drugs was from Mendoza, who would later go on to direct Duterte’s first two State of the Nation Addresses. Mendoza has always claimed to maintain a certain political distance from the subject matter of his films, many of which are about Filipinos living in abject poverty. And 5 years since its release (and Jaclyn Jose’s Best Actress win at the Cannes Film Festival), Ma’ Rosa does seem to present a rudimentary – though still factual – account of police corruption and their harassment of the poor. It still displays an acute understanding of how easily money changes hands between criminals and criminal-cops in small, urban communities. But after seeing how willingly Mendoza has participated in Duterte’s own mythmaking, it becomes difficult to see Mendoza’s gaze as one of empathy and not simply base fascination with the plight of the poor.

Purgatoryo (dir. Derick Cabrido, 2016)

If Ma’ Rosa plainly shows us Duterte’s war on drugs at the onset of his administration, then the QCinema entry Purgatoryo imagines the worst possible outcome of six years of unchecked extrajudicial killings. Brutal and disturbing (to a fault, perhaps), the film follows an ensemble of characters who have built themselves multiple illegal streams of revenue using the corpses that pile into their morgue every day. Its bleak, almost dystopian view of Filipino society – where working people have been reduced to defiling bodies instead of organizing or calling for change – certainly didn’t provide any actionable ideas in 2016. But it now comes across as eerily relevant, as a sort of warning sign of what was to come. Today we definitely need more nuanced commentary than what Purgatoryo offers, but as a manifestation of the fear that Duterte’s campaign promises would spiral out of control, the film works as a cathartic scream of horror.

Tu Pug Imatuy (dir. Arbi Barbarona, 2017)

Among the many groups of people who have been belittled, persecuted, and demonized by the present administration, the Lumad are one sector of many peoples whose struggles against land-grabbing, displacement, and state-sponsored killings rarely get represented on film. Barbarona is one of the few directors working today who is committed to telling their stories, foregrounding them against clashes between the military and the New People’s Army. And while other Filipino directors are still putting actors in blackface in order to play indigenous characters, Barbarona actually employs Lumad people in central roles. In Tu Pug Imatuy, Malona Sulatan and Jong Monzon play a couple who are captured by soldiers and forced to point the way towards suspected rebel hideouts. This story would have been relevant under any administration, but is only more urgent under our current president, who has explicitly threatened wholesale extermination against indigenous peoples. As unpolished as it may be, Barbarona’s film is braver than most, and raises the question of why the industry won’t fund these stories more often.

Respeto (dir. Treb Monteras II, 2017)

One of the more popular films of the last 5 years to really engage with the Philippines’ history of violence, Respeto uses the evolution of Filipino spoken word poetry (from the Balagtasan to FlipTop rap battles) to illustrate how, in contrast, violence only continues to repeat itself. It’s one of many independent productions that has managed to get past potential censorship by placing its criticisms against Duterte within memories of Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship. But this film doesn’t just invoke the Martial Law era as an excuse. At its heart is the unresolved trauma endured by survivors of that regime—who have had to watch as the old dictator’s children attempt to rewrite their family as heroes, while the new dictator allows them to maintain positions of influence and power. Respeto states that, unless we do something, the same kind of trauma might just kill the hope and creativity of this new generation of survivors.

Ang Panahon ng Halimaw (dir. Lav Diaz, 2018)

Despite its obvious stylistic differences, Diaz’s four-hour, black-and-white a cappella musical is surprisingly similar to Respeto. This film also draws clear parallels between the Marcos regime and Duterte’s current rule, and it also places a poet (this time played by Piolo Pascual) at its center. Then and now, strongmen have displayed their weaknesses by going after artists, teachers, and doctors—trying and failing to emulate the good that these people bring to the world. Diaz demonstrates this through language, blessing the heroes with beautiful, ornate words, and cursing the villains with crude, inelegant chanting. Like all of Diaz’s works, it’s an incredibly audacious film that still struggles to find a wide audience in the Philippines, in part due to our country’s highly profit-driven industry and the lack of avenues dedicated to arthouse fare. So while a Diaz film might make waves abroad, there are still many forces here at home that stifle alternative cinema.

BuyBust (dir. Erik Matti, 2018)

Three years since its release, BuyBust remains a bizarre experiment: an attempt to bring together the mass appeal of action cinema (not to mention the built-in fanbase of lead actress Anne Curtis) and the very real and very painful experience of police barging into poor communities and massacring civilians. So while this film definitely had no trouble finding an audience, its messaging remains divisive. Is it a satirical take on the hypermasculinity flaunted by Duterte and his most ardent followers? Does it make too entertaining a spectacle out of poor Filipinos being killed? Is its ultimate message about police corruption earned after two hours of bloodshed? No matter how one feels about it, BuyBust proves that extrajudicial killings and the war on drugs can absolutely be discussed critically in the realm of entertainment. But with this access to a wide platform comes the filmmakers’ responsibility to ensure that entertainment never takes precedence over justice.

Madilim ang Gabi (dir. Adolfo Alix Jr., 2018)

This Pista ng Pelikulang Pilipino entry follows a couple looking for their missing son, just as they’ve decided to quit the drug trade. At first glance, the film seems to understand that “turning over a new leaf” isn’t so simple for people held down by poverty. But in hindsight, the film has become noteworthy not for its ideas but for its director. It didn’t take Alix two years to move from this transparently anti-drug-war movie to directing Bato: The General Ronald dela Rosa Story—a propaganda film lionizing the titular police chief (and one of Duterte’s most recognizable accomplices in his campaign to kill small-time drug pushers) mere months before he was elected senator. Alix isn’t the only filmmaker to walk back on their supposed principles. But the fact that he isn’t alone reminds us that, for many filmmakers, cinema isn’t about generating empathy or nurturing our culture, but serving whoever pays the highest.

A Thousand Cuts (dir. Ramona Diaz, 2020)

The year 2020 finally saw the local releases of two feature documentaries about Duterte’s attacks on press freedom and the poor. The first of these films, A Thousand Cuts, is arguably aimed more towards international viewers rather than a Filipino audience that already understands just how dangerous it’s been to report on Duterte during his term. But while the film might not necessarily reveal any new information for us, there’s still a sense of satisfaction in knowing that it exists at all—and that Filipino censors can’t stop international audiences from accessing it. Still, we can’t expect documentaries to immediately solve any problems; just days after the film’s local release, its main subject, Rappler CEO and co-founder Maria Ressa, was convicted of cyberlibel. Filmmakers might be able to commit the truth to video and celluloid, but the battle that needs to be won is offline and alongside other people.

Aswang (dir. Alyx Arumpac, 2020)

A month after A Thousand Cuts was released in the Philippines, Arumpac’s feature documentary on Duterte’s war on drugs also had its local online premiere. Acting almost as an unintentional response to the previous film’s internationalized, middle class perspective, Aswang covers the brutal effects of extrajudicial violence from the point of view of the ordinary people who are surrounded by it every day. One might argue that Arumpac’s film also restates facts and accounts that are already common knowledge. But it’s in the way the film packages its stories – using the titular creature from Filipino folklore to explain how monstrous our police have become – that Aswang asserts itself as a unique and valuable record of history. Still, as important as the film is, the question of access remains. Online streaming severely limits the audiences that can see these movies, and the ongoing pandemic makes it too risky to stay inside a cinema. Being a filmmaker in 2021 should also mean taking on the responsibility of challenging the limits of our existing models of distribution.

The Kingmaker (dir. Lauren Greenfield, 2019) and A Rustling of Leaves: Inside the Philippine Revolution (dir. Nettie Wild, 1988)

The struggles of the Filipino masses are also universal struggles against tyranny, and toward genuine revolution that actually has their well-being at heart. So it shouldn’t be surprising that some foreign filmmakers have also taken an interest in chronicling the country’s bloody political history. Two more documentaries that studied just that found their way to the Philippines in 2020, despite the potential dangers of having them screened.

In a twist of irony, the American film The Kingmaker, a biographical documentary on Imelda Marcos’s twisted and ultimately destructive view of reality, had its local premiere at the Cultural Center of the Philippines—established by the Marcoses themselves. The premiere happened a year after the film started making the rounds at over a dozen international film festivals. Meanwhile the 1988 documentary A Rustling of Leaves, directed by Canadian filmmaker Nettie Wild, was finally made available to Filipino audiences in 2020, through the Daang Dokyu film festival. Set during Cory Aquino’s presidency, the film documents the activities of both left- and right-wing groups either fighting to maintain the new, post-Marcos status quo or fighting to claim liberation from the ruling elite.

Neither of these documentaries is explicitly about our current president, but both films still echo into today’s political landscape—inhabited by delusional fascists, and violently opposed to any ideologies or movements that seek to redistribute power and resources to the people. It’s distressing that the state of our nation now appears so similar to how it was under our previous dictator. But at the very least, these films reassure us that the struggle for justice and liberation will never disappear from memory. One way or another, cinema will always find a way to break through the restrictions of our industry, no matter where it has to happen, no matter how long it takes. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Only IN Hollywood] Restored ‘Bona’ draws raves as biggest Filipino delegation gathers at Cannes](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/Cannes20242Ruby-Ruizs-right-first-film-was-with-Nora-Aunor-and-Rustica-Carpio-in-Bona.-I-was-18-years-old-Ruby-recalled.Credit-Carlotta-Films1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=313px%2C0px%2C1350px%2C1350px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.