SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

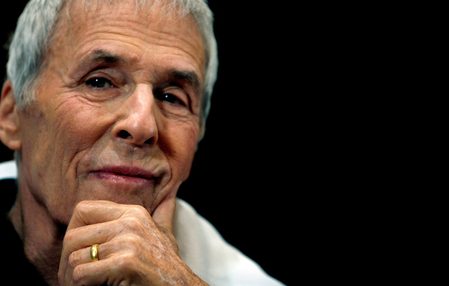

![[Only IN Hollywood] I say a little prayer and a lot of thanks to Burt Bacharach for his music](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/burt-pebrero-09-2023_PEOPLE-BACHARACH.jpg)

LOS ANGELES, USA – LA is a great big freeway / Put a hundred down and buy a car / In a week, maybe two, they’ll make you a star / Weeks turn into years, how quick they pass / And all the stars that never were / Are parking cars and pumping gas

As a boy growing up in Pangasinan, hearing Dionne Warwick sing that “LA is a great big freeway,” complete with a catchy pop hook, was one of my first introductions to Burt Bacharach.

“Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” and its infectious melody conjured an intriguing image of California, but it seemed so distant from where I was, in a town called Calasiao. I played games with friends while we sang out loud:

Why do birds suddenly appear / Every time you are near? / Just like me, they long to be / Close to you

Thanks to radio stations in nearby Dagupan City, we knew the lyrics of Hal David and the infectious music of Bacharach, but we did not know these two talents behind the songs then. We just knew them as hits of Warwick, The Carpenters, Herb Alpert, B.J. Thomas, The 5th Dimension, and Roberta Flack.

At home in a barrio called Gabon, I still remember holding the gold-colored album, Dionne Warwick’s Golden Hits Volume 2, and playing the vinyl record on our stereo turntable set – back then encased in a humongous cabinet and on each side, tall standalone speakers.

Eventually, I learned that “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?,” “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” “I Say A Little Prayer,” “Walk on By,” “Trains and Boats and Planes,” “What’s New Pussycat?” and many more came from the pop genius songwriting collaboration of Bacharach and David. Together, the duo composed many songs, with more than 70 landing in America’s Top 40 charts.

Bacharach’s TV specials – regrettably, they do not make shows like those anymore – enabled me to see this pop maestro playing the piano, even singing, or accompanying talents from Warwick, to Tom Jones, to Dusty Springfield to Barbra Streisand.

When news spread around the world that Bacharach passed away last February 8, tributes poured in.

Paul McCartney, in an emotional thread on Twitter, wrote, “Dear Burt Bacharach has passed away. His songs were an inspiration to people like me. I met him on a couple of occasions and he was a very kind and talented man who will be missed by us all. His songs were distinctive and different from many others in the ’60s and ’70s…”

Elvis Costello, a longtime pal and collaborator, said, “I’m not ashamed to say I did love this man for everything he gave, Mr. Burt Bacharach.”

Warwick, who had a series of almost 40 consecutive chart hits with Bacharach and David, said in a statement, “Burt’s transition is like losing a family member. These words I’ve been asked to write are being written with sadness over the loss of my dear friend and my musical partner.”

“On the lighter side, we laughed a lot and had our run-ins but always found a way to let each other know our family, like roots, were the most important part of our relationship. My heartfelt condolences go out to his family, letting them know he is now peacefully resting and I too will miss him.”

Warwick first met Bacharach when he asked her group, which included her aunt Cissy Houston (the late Whitney Houston’s mom) to sing background vocals in a recording of The Drifters. He also asked her to sing on several demo songs that he was offering to record companies.

Pop lore has it that Florence Greenberg, an executive at Scepter Records, exclaimed to Bacharach, “Forget the song. Get the girl!”

Bacharach and Warwick’s working relationship hit a snag when the film Lost Horizon, which he scored and for which he and David composed songs, flopped commercially and artistically. It was one of the songwriting duo’s rare failures. As a result, the two stopped working for a while, which impacted Warwrick’s career.

Warwick sued Bacharach and David for breach of contract. But eventually, the case was resolved and the three were on good terms again in later years.

Bacharach, in a 2016 interview with the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA), said about his and David’s muse: “Whenever we wrote something for Dionne, and we recorded it, we could see where the possibilities lay. They were intimate because she was capable of doing so much.”

“Make it three octaves? Yeah, she could do that. And she was capable of this and that. So it gave me the liberty and the chance to widen the musical scope.”

In that same HFPA interview, Bacharach recalled how he and David met in 1957 in New York: “We all wrote in a place called The Brill Building on Broadway.” Bacharach recalled how the songwriters systematically worked with each other: “[We] took turns writing with different people – writing with someone in the morning and somebody in the afternoon.”

“I was interested to work with Hal. We wrote some really bad songs. I mean, they weren’t all hits. There is a song called ‘Peggy Is in the Pantry’ which you will never hear. How about ‘Underneath the Overpass,’ which you will also never hear.”

“So when we did hook up together and start writing, it was like going to the office. We would meet at 1619 Broadway (Brill Building) and have a little office there, a very broken down piano.”

“Hal constantly smoked…in a room with a beat-up piano. I think I wrote some pretty good songs with Hal that didn’t turn out well and were not recorded well. The A&R man changed chord progressions and the arranger changed things. So I think we lost some songs that might have been very good and important.”

The Kansas City, Missouri-born composer recounted how he got his first big break: “There was a man named Calvin Carter…. He was an A&R man at Vee-Jay Records in Chicago. He said, ‘You got a song called ‘Make It Easy on Yourself’ that you and Hal wrote. I want to record it with Jerry Butler. I want to bring Jerry in from Chicago into New York. You book the session, get the band and singers you want, and write the orchestration. It’s basically your session.’”

“So somebody was giving me the freedom to take that piece of music and take it to the next step as I heard it. It was very freeing because if it works, you can pat yourself on the back. If it doesn’t work, you cannot blame it on any arranger or the A&R man. You can blame it on yourself.”

“So I am always indebted to Calvin Carter for that break. It’s like your first movie. You want to do a movie, you go in and you can’t get it, and then you get that first movie.”

Bacharach, often with David, went on to win many awards, including eight Grammys, three Oscars, and two Golden Globe Awards. The two gifted us with some of the most beautiful pop gems of the 20th century.

Music journalist Mark Voger wrote about Bacharach’s oeuvre, “It may be easy on the ears but it’s anything but easy. The precise arrangements, the on-a-dime shifts in meter, and the mouthfuls of lyrics required to service all those notes have, over the years, proven challenging to singers and musicians.”

On Wikipedia: “Bacharach’s selection of instruments included flugelhorns, bossa nova sidesticks, breezy flutes, tack piano, molto fortissimo strings and cooing female voices.”

Which one is the greatest Bacharach composition could be subject to a long and passionate debate: “Alfie,” “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “Walk on By,” “The Look of Love,” “Make it Easy on Yourself,” and “I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself.”

There’s more: “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” “Arthur’s Theme,” “What the World Needs Now is Love,” “On My Own,” “A House is Not a Home,” “That’s What Friends Are For,” and “Close to You.”

The list goes on. When Bacharach died, I learned about other pop classics that I did not know he composed.

On his songwriting process, what he needs – tea, wine, or a favorite chair – Bacharach answered, “I need my mind. And the keyboard because I write a lot in my head. I check things out then at the keyboard. It’s a different process. I need to see the long length of what the music is.”

“If you sit at the piano, you maybe get trapped into the four bars by four bars and they sound good, but how does it work and relate through 32 bars?”

“I wish I could say, ‘Yeah, every day I go to the piano.’ The intent is there but it’s dishonest for me to say every day.”

As to which songs were the easiest and hardest to compose, Bacharach replied, “Easiest, fastest, quickest song – ‘I’ll Never Fall In Love Again’ from Promises, Promises. I was in Massachusetts with pneumonia and we had Promises, Promises on the road.”

“I got out and they needed a song to go in the show maybe by the next day. I sat at a piano with Hal David and that’s where that line came from, what do you get when you kiss a guy, you get enough germs to catch pneumonia. Great line. The hardest song was maybe ‘Alfie’ because I thought it was a really very important song.”

Bacharach was quoted as saying in another interview about “Alfie,” the theme song from the 1966 movie of the same title starring Michal Caine: “‘Alfie’ could be as close to the best song Hal and I ever wrote. It was a hard one to write because most of it had to be said lyrically at first.”

“I had to set it musically and it was challenging but it turned out great. We went in and recorded it quickly with Dionne (Warwick) because the original record was with Cher. Sonny (Bono) made the record with Cher and that was different than how I had envisioned it.”

In the HFPA interview, Bacharach recounted how “Alfie” began: “I had the whole lyrics of ‘Alfie,’ so I said it, making a few changes as we went along. But, I just knew, ‘Are we meant to take more than we give,’ lines like that, I mean really, they do really honest justice.”

He added about his collaboration with David, who died at 91 in 2012, “Sometimes he would come in with complete lyrics or half a lyric and I would have maybe four bars of a melody and we would kind of ping-pong off that.”

On how he landed What’s New Pussycat?, his first of a dozen film scoring projects, Bacharach recalled a fateful encounter in London. “That was luck, that was sort of like the Jerry Butler thing, of being asked to record it. I was in England with (actress) Angie Dickinson and we hadn’t gotten married yet. Angie ran into Charlie Feldman (producer) and he had this movie.”

“He was at The Dorchester and he said, ‘Angie, what are you doing here?’ And she said, ‘I am here with this guy.’ ‘What does he do?’ ‘He writes music.’ ‘Is he any good?’ And Angie says, ‘Yes, really good.’ ‘What has he written?’ ”

“Angie gave him a couple of titles. Charlie went up to his suite and saw his lady and said, ‘Do you know ‘Walk on By?’ ‘Anyone Had a Heart?’ And she said, ‘I love those songs!’ And that is how I got What’s New Pussycat? That’s how I got my first movie. See, by accidental happenings and occurrences.”

Like being recommended by fellow composer Peter Matz to Marlene Dietrich, who was looking for an arranger and conductor for her club shows in 1956. At age 28, Bacharach was touring the world with the film icon and chanteuse.

“One essential lesson I learned from Marlene was if you want to get something done, you do it yourself, do not delegate,” he recounted.

He revealed, “With Dietrich, the music sucked. It truly did. I didn’t like the music I conducted. It was a job, it was a way to see the world, to go to Israel, to see what was happening in Germany when they didn’t want her there because she fought with the enemy. That’s why. So there were interesting things like that.”

He shared the last time he spoke to the movie legend: “She always wanted to do one more song to record with me. She wanted to do ‘Any Day Now’ and we were going to record it in her apartment. She had this idea that I was going to put the microphone under the door and we would record it that way. But then she died.”

Scoring the 2016 film A Boy Called Po, directed by John Asher, inspired by the true story of a widowed engineer who struggles to care for his autistic son, was an emotional experience for him.

“I had a daughter with Angie Dickinson very early on in the advent of autism,” he shared. “Nikki would probably be 56 or 60 now. And nobody knew what autism was at the time. It was very puzzling. So now we know what it is and we don’t know what causes it.”

Bacharach penned the theme song with Billy Mann, “Dancing with Your Shadow,” performed by Sheryl Crow. “There was never an intent to have a song. The intent was to score the film and be true to the film. I guess every film that I have done, has centered on what that person, or what the situation looked like, whether it was that first movie, What’s New Pussycat?”

“And looking at Peter Sellers as Dr. Fassbender and coming up with the theme, ‘What’s New Pussycat?’ So, being honest with the medium and what you are writing. Not trying to have a hit, just being true to service the film.”

“So with Po, I just had to get something melodically that was simple for me, this theme, and was written with this character and person, with no thought of, is it going to be a song, can we make it a hit, nothing.”

“John asked me to play at the end of scoring one day and I reiterated that theme and another theme as well. Then we got Billy Mann who has two autistic children. Billy wrote these brilliant lyrics.”

“So out of no intent to have a song, a song became born. So to get this lyric and all being connected, had I played the song, say for Angie? No. Would I like to play it for Angie? Yeah. Is it safe? I don’t know.”

“Wounds are very deep for Angie because Nikki couldn’t take it anymore and killed herself. So it’s a very hard one. It’s like seeing the film – same thing, it might be too hard for her. So a song was born without intending to be born. Sometimes I do believe that is the best way.”

Asked who among the contemporary crop of film composers he admires, Bacharach answered, “I like James Newton Howard and I think he is brilliant. I just have to hear more of this crop of films. There is a lot of music I have heard on films that seem covered with sounds and synthesizers, more like effects, just sound.”

The son of a syndicated newspaper columnist and an amateur painter and composer did not enjoy taking classical piano lessons. Instead, he discovered the likes of Dizzy Gillespie and Count Basie in New York nightclubs.

Their jazz harmonies influenced Bacharach even as he enrolled at Montreal’s McGill University, New York’s Mannes School of Music, and Montecito, California’s Music Academy of the West.

Over the years, Bacharach kept and sometimes lost precious mementos. “There was a letter from Richard Rodgers after he saw Promises, Promises at a matinee, with five substitutes in the band,” he volunteered.

“When I heard that happened, I was like oh Jesus, this is the worst. But he wrote me this great letter. It was lost for five or six years, and I finally found it, gratefully.”

Married four times – to Paula Stewart, Angie Dickinson, songwriter Carole Bayer Sager, and Jane Hansen – Bacharach commented, “If it’s not working, get out. If it’s broken, it’s not worth the house or the money and the grievance, everything. Give it all away. You just have one life.”

He was married to Hansen for 30 years at the time of his death. “[She is] definitely a keeper – the mother of these two (Oliver and Raleigh).”

In the 2016 chat, he reflected on his longevity. “I have two young children, and at my age, it’s kind of unusual to be my blood and everything. One is 23 and another is 20. Kind of unusual. So this part of my life, it’s about this family and these kids and being there for them as long as I can be there for them.”

“And there are no guarantees. You can do everything that is possible to do to stay healthy, to eat the right food and to exercise every day and be gone in a minute. So genes, maybe. My mother lived to 85, my dad lived to 85 so genes are pretty good, I would say.”

“And not smoking, I am sure, is a big help. And never being down. There’s something always to do, to make music or go to the piano and even if you are not going to write anything, just to be in touch with your muse.”

Bacharach died at 94.

I ended up living in LA and I discovered, when I arrived as an immigrant, that it is indeed a great big freeway. I did not become nor wished to be a star. I was not parking cars and pumping gas either.

But as Warwick sang, weeks do turn into years, and how quickly they pass.

What has remained fresh and timeless is Burt Bacharach’s music. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.