SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Patricia Evangelista never planned on writing a book.

“No, not at all,” the former Rappler investigative reporter quickly replied when asked if publishing her own book was something she had set out to do.

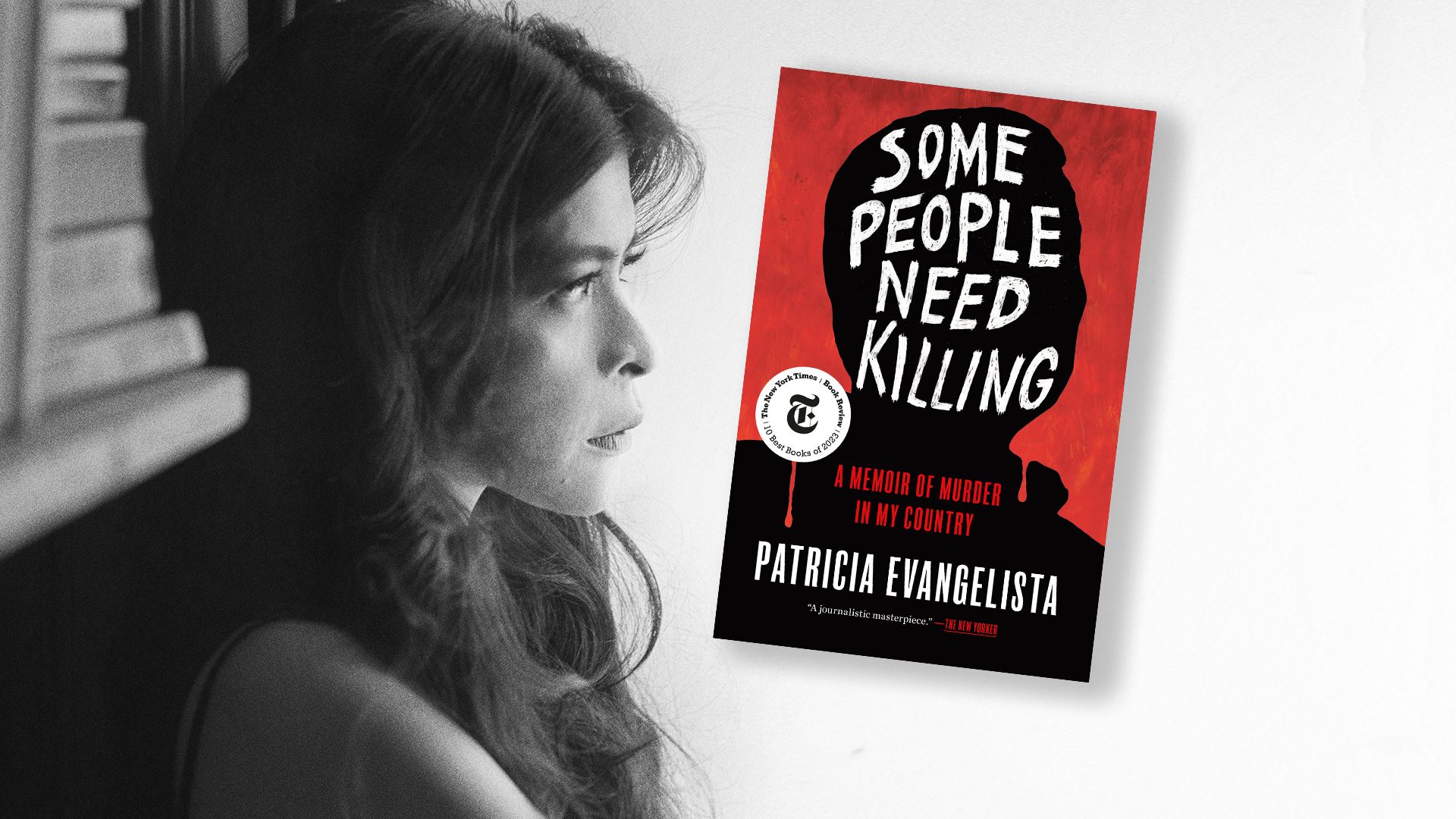

Eventually, however, she went on to author one of the most critically acclaimed pieces of literature in 2023 – Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country. The captivating memoir sees Evangelista vividly recount her coverage of former President Rodrigo Duterte’s deadly war on drugs, which led to the unjust killings of thousands of Filipinos.

Since its publication in October 2023, it was named among the New York Times’ 10 Best Books of 2023, the New Yorker’s Best Books of 2023, and TIME Magazine’s 100 Must-Read Books of 2023, among others.

In an online question-and-answer session with Rappler on Tuesday, April 2, Evangelista shared how the book came to be, what she keeps in mind as a trauma reporter, and how the success of the book changed things for her.

The memoir’s origins

In 2018, Evangelista had been in the midst of completing her Murder in Manila series, where she investigated the police’s alleged outsourcing of vigilantes to carry out extrajudicial killings for the drug war.

“When the story was coming into fruition and it was clear that we were going to publish and I had been interviewing vigilantes and policemen, there was a risk. It was considered in my best interest not to be in the country when the story was going to be published,” Evangelista said.

In New York, Evangelista entered a nonfiction fellowship. She had no intention of writing a book. But with the help of her friend and literary agent David Granger, she had submitted a proposal for her book anyway, which she decided would center on the drug war.

The memoir had initially been written in the third-person point of view, akin to a reporter’s notebook. But with the grimness of the drug war, Evangelista’s publishers had deemed it fit to be written in the first-person point of view instead.

She was already two years into the process when she decided she was going to be a character in the book. Even then, she still had to figure out what her own voice was outside of the usual reporter’s third-person voice that she had gotten so used to telling her stories with.

“As it went along, it felt that [the publishers] were correct, na dapat pala first-person ‘yung libro kasi I was writing not just as a reporter. I was writing as a Filipino, as a citizen, so there was no way na kayang i-explain ‘yung filter ng nakikita ko without saying who I was and where I come from,” Evangelista said.

(As it went along, it felt that the publishers were correct, that the book really should have been written in first-person because I was writing not just as a reporter. I was writing as a Filipino, as a citizen, so there was no way to explain the filter I was seeing without saying who I was and where I come from.)

Telling stories of trauma

Covering the drug war and writing her book meant that Evangelista had spoken to a myriad of interviewees who all carried trauma with them. But in any kind of trauma reporting, Evangelista finds it important to make it clear to her interviewees from the beginning that she’s there as a reporter.

“Hindi mo pwedeng ipangako na, ‘’Pag ikwento mo sa akin ‘yung pinagdaanan mo, makakakuha ka ng hustisya.’ Hindi mangyayari ‘yun eh, at kung mangyari man, hindi mo mapapangako kasi hindi mo alam. So, make sure it’s clear that you’re there just as a reporter, to tell the story, that all you promised is the story because if you promise many things, you’ll re-traumatize people in the aftermath as well. And you’re getting your story on false pretenses,” she said.

(You can’t promise them that, “If you tell me about your experiences, you will get justice.” That won’t happen, and if it does, you can’t promise that because you wouldn’t know. So, make sure it’s clear that you’re there just as a reporter, to tell the story, that all you promised is the story because if you promise many things, you’ll retraumatize people in the aftermath as well. And you’re getting your story on false pretenses.)

Consent is also key for Evangelista. While she had received permission from the parents of the kids she interviewed during the drug war, she felt it was necessary to ask for the kids’ consent again when her book’s publication date drew nearer as it wasn’t just the Philippines that would be able to read the memoir – but the world, too. They had already been 18 years old at that point, so they were able to personally grant Evangelista consent to tell their stories in the memoir.

“The most [important thing] in a trauma interview or interviewing people in the aftermath of trauma, is not to re-traumatize. Not to make them go through the hell that they don’t want to go through. If they feel telling the story is good, is important, that’s great. Pero walang (But there shouldn’t be) compulsion. Consent is always important,” she explained.

Beyond the numbers

Having been exposed to the drug war and the families that have become victims of it, Evangelista is able to look far beyond the numbers in the death toll. She has the privilege of hearing these families’ stories and carrying them with her for life – and her memoir is a testament to that.

“I think we should listen more to people. I’m no more moral than anyone else but I think my advantage, like a lot of drug war [and trauma] reporters, is that we hear people tell the stories. I can’t say that there’s something wrong with society just because they see the numbers. They don’t have the privilege of seeing the story in front of them, so I think our job as reporters is to tell the story in as human and a personal way as possible,” Evangelista said.

In writing Some People Need Killing, Evangelista merely wanted to honor the people in the story and get the facts right. It came as a total surprise for her when the acclaim began pouring in. She admitted that until now, she is still trying to accept the praise it has received so far.

But Evangelista also said that numerous people who had read her book thought it was “too sad.”

“Not that the book isn’t sad, it is, but they’re angry that it is. They’re surprised. The book is about the death of thousands in a country. There is no happy ending. It’s not a spoiler. There’s no happy ending, and that’s what people demand: hope. I am not good with hope, at least in this particular book,” Evangelista explained.

More than anything, however, the success of her book also brought significant changes for Evangelista, who stood as a character in the story so she could tell it to the whole world.

“[Before], my byline was there but I wasn’t. Hindi ako kailangan ng istorya (The story doesn’t need me). The book changed things because now I’m in front of it. It’s a personal story, and it requires that I tell it because the story is important to the Philippines,” she said. – Rappler.com

To watch the full interview, be a registered Rappler user for free! Once registered, you will be able to watch the entire interview on this page.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.