SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BAGUIO CITY, Philippines — On the early morning of December 15, a barangay tanod (village watchman) handed Marie (not her real name) a letter for a meeting with the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

Attached with the note was a letter from a certain Police Lieutenant Laurence Aspilan, requesting Barangay Captain Arthur Carlos of Irisan, Baguio City, to facilitate a “personal dialogue” between him and Marie.

“(W)e are asking at your most convenient time to talk with her that I would like to engage her personally…,” Aspilan said.

Carlos confirmed the letter and the PNP request in a phone interview. He said the police did not explain why they wanted to talk with Marie.

Marie, a community health worker and activist, said she was not surprised about the incident.

“Somehow, I was expecting this. I have no illusion that they [police] will spare me from these things,” she said in a mix of Filipino and English.

Marie has had several experiences with being red-tagged. This time, however, she said the request brought chills and serious fears about potential harm.

“I am concerned for the safety of my family, especially the kids. What if they come to our house and try a tokhang approach,” Marie shared.

Tokhang, from the Visayan words, knock (tok) and plead (hangyo), is the catchphrase of the Duterte administration’s “war on drugs.” It is linked to the government’s “nanlaban” (fought back) narrative in the killings of thousands of drug suspects during police operations.

‘Visit and talk’

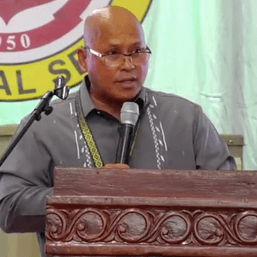

In the past months, red-tagged Baguio activists have experienced rising incidents of unwanted visits and calls for “dialogues” by the police. The topic inevitably is their alleged connection with communist rebels, said Tongtongan ti Umili chairperson Geraldine Cacho.

The “Dumanon Makitongtong” (visit and talk) strategy adopted by the Cordillera Regional Peace and Order Council (CRPOC) in July is patterned after tokhang, Cacho said in an interview with Rappler on Thursday, December 15.

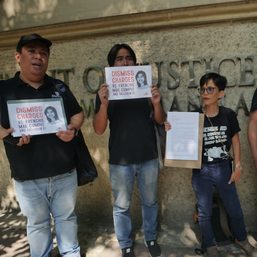

The Regional Law Enforcement Coordinating Committee (RLECC) in February also passed a resolution encouraging the conduct of Oplan Tokhang against “leftist personalities”.

The measure urges law enforcement personnel with local government officials, and civil society groups to visit the homes of “known members of communist front organizations (CFO).” The CFOs are almost always legal activist groups.

The aim is to convince the suspected communist sympathizers or members to stop supporting the rebels – even when the target is a legal personality.

Cacho, who also resides in Irisan, said that police started visiting their barangay in March, profiling members of the urban poor group Organisasyon Dagiti Nakurapay nga Umili ti Syudad (ORNUS).

She said these unwanted visits “generate fear and concern to the individual being tagged as rebel supporter and also to the neighborhood.”

“When police or military come to your place or ask about you, the usual connotation is that you have done something wrong or a crime,” she pointed out.

Retired PNP Chief General Guillermo Eleazar initially expressed concern about the strategy, saying “gray areas” may compromise their human rights commitment. However, hours after, he backtracked and voiced support for the measure.

In August, the New York-based Human Rights Watch warned of the “potentially catastrophic move” and urged officials in the region to rescind the resolution.

“Using the same ‘drug war’ methods to go after suspected rebels is a potentially catastrophic move that will be no different from the rights abuses we’ve seen in the ‘war against drugs’ by the Duterte administration,” said HRW Asia Senior Researcher Carlos Conde.

“Measures like this will definitely constrict even more the democratic space in the Philippines because it makes civil society actors, among them human rights defenders, targets for violence,” he said.

Cause for concern

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) acknowledged in its 2020 Annual Report that red-tagging is a critical concern, especially among indigenous peoples. It noted that individuals accused of supporting or membership with the communist rebels experienced heightened attacks.

The office recommends that state institutions should “desist from red-tagging and labeling [human rights defenders] as terrorists or enemies of the State, and other similar acts.”

In the Cordillera, red-tagging remains pervasive, with CHR Cordillera noting a significant rise of cases from last year. This is despite a Baguio court order and a resolution from the CHR regional office stating that such action endangers lives and violates human rights.

In June 2020, the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights had also expressed concern about the issue. The agency said the blanket labeling of activists as communist rebels “posed a serious threat to civil society and freedom of expression.” – Rappler.com

Sherwin De Vera is a Luzon-based journalist and an awardee of the Aries Rufo Journalism Fellowship.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] A little walk-back](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/tl-a-little-walk-back-05182024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=215px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.