SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

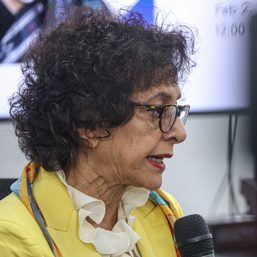

For the second time around and on the basis of a complaint by the same businessman, Rappler CEO Maria Ressa was charged on November 23 with cyber libel over a tweet.

Prosecutors claimed Ressa’s tweeting of a Philstar.com story published in 2002 was malicious. The news group, saying it was threatened with legal action, took down the article the same day Ressa tweeted the screenshot.

This is uncharted territory for the new Philippine cybercrime law. Ressa filed a motion to quash on Wednesday, December 2, citing a Supreme Court decision that says aiding and abetting a cyber crime is not a crime in itself. In this context, it refers to tweeting screenshots of a supposedly libelous article.

The complaint was filed in February 2020 in Makati by businessman Wilfredo Keng, whose earlier suit in Manila got Ressa and former researcher Reynaldo Santos Jr convicted of cyber libel in June this year. The conviction is on appeal at the Court of Appeals (CA).

In charging Ressa before a Makati court on November 23, Makati prosecutors said that the journalist’s tweeting of screenshots was not a mere act of sharing – an act, which the Supreme Court ruled, could not be described as criminal because it constitutes knee-jerk internet reaction.

“Obviously, the foregoing cannot be considered a knee-jerk reaction on the part of respondent, hence, she should be liable for the consequences of her Twitter post,” said the resolution signed by Senior Assistant City Prosecutor Mark Anthony Nuguit, and approved by Senior Assistant City Prosecutors Aris Saldua-Manguera and Roberto Lao.

The motion to quash prepared by Ressa’s lawyer Ted Te of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), said: “(Ressa) is not the author of the defamatory PhilStar.com article, she cannot be made liable for sharing or RT’ing the content under Section 4(c)(4) (online libel).”

Ressa posted bail on Friday, November 27, before Makati City Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 147 Judge Maria Amifaith S. Fider-Reyes, who issued the arrest warrant that same day and set bail at P24,000. This is Ressa’s 9th arrest warrant for what she claims are “politically motivated charges” meant to intimidate her.

PhilStar takes down its story

The case stemmed from a tweet that Ressa posted on February 16, 2019, three days after the journalist was arrested for the Manila case.

Ressa tweeted screenshots of an August 12, 2002 Philstar.com article linking Keng to an alleged murder. On the same day in February 2019, Philstar.com issued a statement that said it had removed the 2002 news story from its site because, according to the news organization, Keng had raised “the possibility of legal action” against the company.

Ressa had argued to prosecutors that when the Supreme Court upheld the Cybercrime Law, it declared unconstitutional the provision that punishes the aiding and abetting of a cybercrime which, in this context, means sharing a supposedly libelous post.

“Except for the original author of the assailed statement, the rest (those who pressed Like, Comment and Share) are essentially knee-jerk sentiments of readers who may think little or haphazardly of their response to the original posting,” the Supreme Court had said.

“Its vagueness raises apprehension on the part of internet users because of its obvious chilling effect on the freedom of expression, especially since the crime of aiding or abetting ensnares all the actors in the cyberspace front in a fuzzy way,” the Supreme Court added.

Posting of screenshots of deleted articles and posts have been a habit of gutsy Filipino social media users as a way of protesting revisionism, for example.

Not a mere share

In Ressa’s case, Makati prosecutors said the journalist’s posting of the screenshot “involved a series of physical acts and mental or decision-making processes,” citing as example the effort to search for the deleted article, screenshot it, post it on Twitter and make a caption.

“(The Supreme Court) opined that online libel (is not applicable) to others who merely pressed like, comment and share because these are essentially knee-jerk sentiments of readers who may think little or haphazardly of their response to the original posting. In this instant complaint, respondent did not merely press the share button,” said the prosecutors.

Ressa’s motion to quash argued that the only content that the journalist should be accountable for is the accompanying caption of the screenshots, which was: “Here’s the 2002 article on the ‘private businessman’ who filed the cyberlibel case, which was thrown out by the NBI then revived by the DOJ. #HoldTheLine”

“By any reasonable and unbiased reading, the sentence is not defamatory—read singly, none of the words are; read together, the sentence is not. The sentence is correct, true, and factual,” said the motion.

Before filing the complaint, Keng demanded in November 2019 that Ressa delete the tweet and make a public apology “otherwise we shall be constrained to file a complaint for cyber libel against you.”

Ressa had said she will never delete the tweet, reasoning, “Imagine if I said, ‘Well, this a really, really small thing and maybe I’ll just step back just a little bit,’ and then I step back a thousand times and a million times, then I’ve just lost all my rights.”

Ressa faces 7 other charges before the Court of Tax Appeals and the Pasig City Regional Trial Court, stemming from the mother case over the company’s Philippine Depositary Receipts (PDRs), which the Court of Appeals (CA) has ruled to be already cured.

Rappler has said these cases were meant to silence critical and independent reporting under the Duterte administration.

To date, Ressa has posted bail 9 times and has been arrested twice. Aside from the string of cases, Ressa and Rappler have also been on the receiving end of online harassment campaigns for stories that shed light on controversial policies of the Duterte administration.

In July, a global coalition of 78 civil society and journalism organizations urged the Duterte administration to “drop all charges and cease and desist its orchestrated harassment campaign” against Ressa. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] De-weaponizing tax laws: Upholding press freedom and economic growth](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/10/tl-upholding-press-freedom-economic-growth.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.