SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It’s a process that moves like clockwork.

After another lopsided confrontation between Manila and Beijing in the West Philippine Sea comes statements – of condemnation against China, from the Philippines’ National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea (NTF-WPS); in support of Manila, from diplomats of nations who stand with the Philippines; and from China pinning the blame on the Philippines.

Just like clockwork, too, the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) announces the filing of protests, both here and in Beijing.

In the aftermath of back-to-back water cannon incidents in two features in the West Philippine Sea, the DFA tapped three mechanisms – a demarche or a protest before the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing, a protest via the maritime communication mechanism the two countries had set up, and the summon by the DFA of Chinese Ambassador to the Philippines Huang Xilian.

On Tuesday, December 12 – three days after water cannons were used against Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) ships in Bajo de Masinloc, and two days after military-contracted boats and Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) vessels were water cannoned in Ayungin Shoal – the DFA confirmed that a day prior, Huang was summoned “to convey the strong protest of the Philippine Government against the back-to-back aggressive and harassing actions undertaken by Chinese forces against Philippine vessels in the West Philippine Sea over the weekend.”

DFA Undersecretary for Bilateral Relations and ASEAN Affairs Ma. Theresa Lazaro “verbally delivered” the Philippines’ protest. ASEAN stands for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

In Manila, Lazaro asked China to:

- Direct its vessels to stop all “illegal actions” against Philippine ships, stop interfering in “legitimate Philippine Government activities,” stop “lingering in waters around Ayungin Shoal, and doing any action that violates the Philippines’ sovereign rights and jurisdiction in its exclusive economic zone”

- Comply with their obligations under international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the 2016 Arbitral Award, the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea

- Adhere to commitments under the 2002 ASEAN-China Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC)

Lazaro also protested China’s use of dangerous maneuvers and water cannons against BFAR ships in Bajo de Masinloc.

The same points were raised in protests filed in Beijing by Manila’s diplomats stationed there.

Summons and protests under Marcos

The December 11 summon was the fourth – at least that the public knows of – in 2023 alone.

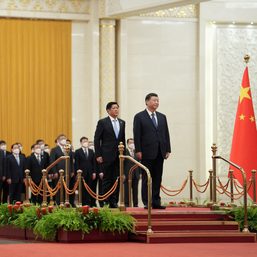

On February 14, 2023, Huang was first summoned by no less than President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. after China used a military-grade laser against the PCG.

He was summoned again in August 2023, by Lazaro too, the first time in 2023, after the China Coast Guard (CCG) used water cannons against Philippine ships en route to Ayungin Shoal. A collision incident in October 2023 prompted another summon, but since Huang was supposedly not in Metro Manila, China’s deputy chief of mission was summoned by the DFA instead on October 23, 2023.

As of December 5, or right before the December 9 and December 10 incidents, the DFA said the Philippines has lodged 63 diplomatic protests against China.

Since Marcos assumed power in June 2022, the Philippines has filed at least 130 protests.

But what role do protests play when, just weeks or months later, the CCG continues to use its might in the West Philippine Sea?

“A protest has both diplomatic and legal functions,” explained DFA spokesperson Teresita Daza.

Protests are a form of formal communication between two countries. In instances similar to incidents in the West Philippine Sea, they’re an “[expression] of a state’s position on a legal issue,” added Daza.

Lodging a protest, said Daza, prevents the perception of “acquiescence” on the part of the Philippines. In the case of the South China Sea, it means that on record and in official communications, the Philippines has been consistent in protesting China’s actions.

It could also be the basis for complaints in the future, including those lodged before mechanisms or bodies that rule on or serve as an arbitration tool between two or several countries.

If, in the future, the Philippines decides to take China to an international body over its more recent actions, it can cite the many protests it has filed to show that it has not only expressed its disdain, but has also tried bilateral and diplomatic measures to improve the situation in the West Philippine Sea.

Diplomatic protests are difficult and complicated documents to draft, especially for situations such as the routine resupply and rotation missions to the BRP Sierra Madre in Ayungin Shoal, where several things are happening all at once.

The premise of the complaint on each action of China against the Philippines at sea, and the Philippines’ corresponding actions must be explained and framed within the context of international laws and rules that apply – among them UNCLOS, Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea or COLREGs, the 2016 Arbitral Award, and the 2002 ASEAN-China Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, to name a few.

On the basis of what?

When the Philippines – and the DFA, in particular – address tensions in areas such as Ayungin Shoal and Bajo de Masinloc, arguments are always anchored on three things:

- UNCLOS

- The 2016 Arbitral Ruling

- The DOC, as well as both ASEAN and China’s commitment to creating a Code of Conduct

The Philippines’ premise – rooted in agreements that China is also a signatory to, and a legally-binding decision that Beijing rejects – explains why Manila and Beijing’s statements on incidents either in Ayungin Shoal or Bajo de Masinloc greatly differ.

When China speaks of these two features – located well within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ), it cites sovereignty. Beijing asserts that these features – surrounded by similar features that have since been transformed into artificial islands – are part of Chinese territory, over which it exercises sovereignty.

The Philippines, for the most part, is clear that in its EEZ and in features like Ayungin Shoal or Bajo de Masinloc, its sovereign right is what is being asserted. “Sovereign rights” means that it’s in those waters that the Philippines has the sole right and responsibility to exploit and protect resources such as marine life and possible energy reserves.

UNCLOS, after all, does not deal with territorial disputes.

The arbitral tribunal, created under UNCLOS, did not tackle territorial disputes but determined that China’s claim of practically all of the South China Sea, its reclamation activities, disruption of Philippines activities in those waters, and destruction to the marine environment, were all unlawful.

The tribunal also said that Bajo de Masinloc, while within the Philippine EEZ, is the traditional fishing ground of fisherfolk from the Philippines, China, and Vietnam. That means no country has the right to bar another from small-scale fishing in the area.

China has rejected – and continues to reject – the ruling, even as major powers in global politics and in the region have declared support for it. ASEAN is especially tepid about the ruling, and has been mostly quiet amid tensions between China and the Philippines in those waters. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.