SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – December 20, 2023, started out as just another day for ELE Group workers in New Zealand.

They had their uniforms on and were ready to go to their respective workplaces – in construction or as assistants to carpenters.

But that morning, according to Filipino worker Nelson (not his real name), he and his fellow hammerhands in ELE based in Hamilton, a city in New Zealand, received messages not to go to work. They were told management was set to hold a meeting where something “important” was to be discussed.

Hours later, they learned that they had lost their jobs.

Just before Christmas, around 500 overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) in New Zealand lost their jobs when labor-hire and recruitment firm ELE Group went under receivership. While accounting firm Deloitte, the receivers of the ELE Group’s companies, estimates around 500 Filipinos were affected, the actual number could be up to more than 700, according to an open letter from the workers.

For weeks, the OFWs relied on community donations, while some slept in their cars. According to Deloitte, none of the workers have received their final pay as of posting. Some have already signed contracts for new jobs.

According to Investopedia, when a company is in receivership, it is placed under control of a trustee because it could not meet its financial obligations. A receivership is a measure that could prevent a company’s looming bankruptcy.

The receivership of ELE Group was what put the OFWs out of work. But just working for a labor-hire company already puts OFWs in an unstable position. This situation is similar to how thousands of Filipino workers in the Philippines experience labor contractualization.

Jobless in a day

At 35, Nelson had been on his 10th year as an OFW when he arrived in New Zealand in 2023. He learned of the opportunity to work in ELE through a friend in the Philippines. Because ELE was a labor and recruitment agency, its contract workers did not work for ELE itself, but instead for companies that the agency contracted them out to. The two companies where Nelson worked had good pay and a schedule that allowed him to rest.

Nelson earned NZD$27 per hour, from 7 am to 5 pm, which meant he normally earned around $1,282 in a week, or P44,344.

Back home in Cavite province, he has a wife and two young daughters, whom he was able to send up to P20,000 every week.

While his family in the Philippines was able to save a portion of his remittances, most of what he kept for himself ran out quickly because of the high cost of living in New Zealand. That’s why when ELE announced to the workers that they were closing and could not give their salary for the week, the Filipinos were left high and dry.

“Sobrang lungkot po. Siyempre, ang unang pumasok po sa isip namin is ‘yung… Alam ‘nyo naman po, ‘pag magpa-Pasko, maraming plano. Lahat po ‘yun is gumuho bigla nang sinabi po sa amin, nang marinig namin na mawalan na kami ng trabaho at sarado na ang kanilang kompanya,” said Nelson in an interview with Rappler.

(We were tremendously saddened. Of course, the first thing that went into our minds was… You know, when Christmas is coming, you have a lot of plans. All of that was gone in a snap when they told us, when we heard, that we would lose our jobs and their company was closing.)

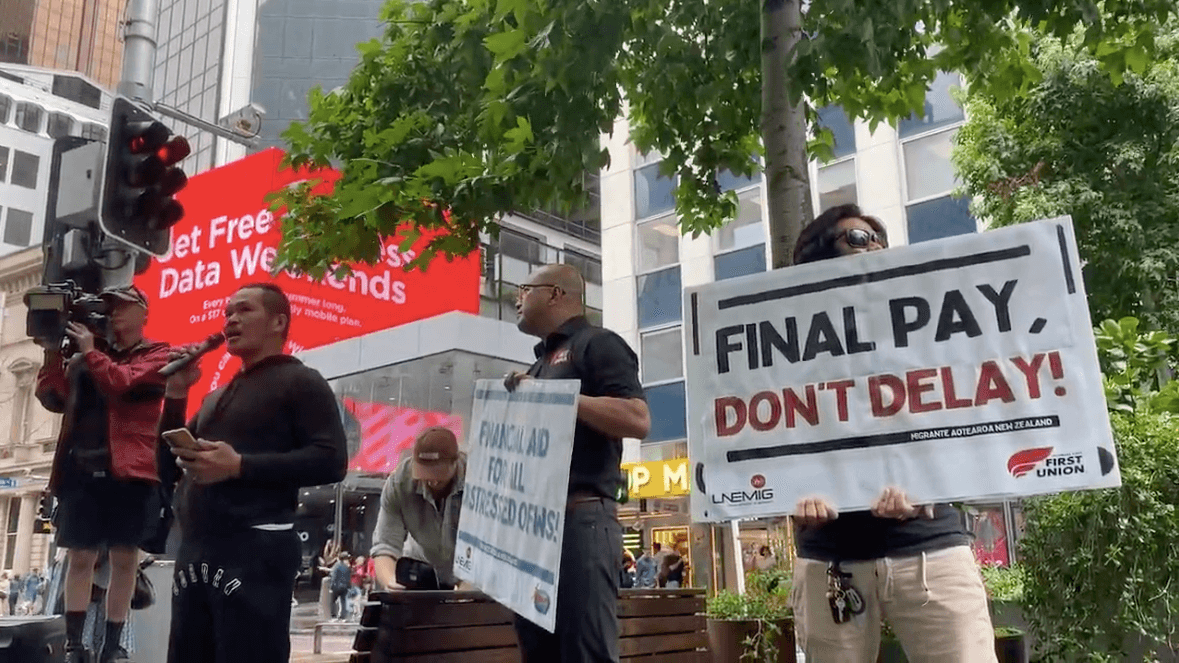

In the weeks of unemployment, workers’ union FIRST Union and OFW rights group Migrante Aotearoa, both based in New Zealand, helped the workers get by through food packs given to them. It took some weeks before the Philippine government shelled out financial support.

No job security

Around half of the Filipinos affected by the receivership were contract laborers in construction, according to Dennis Maga, general secretary of FIRST Union. The union, composed of 30,000 workers from the finance, industries, retail stores, and transportation (FIRST) sectors across New Zealand, is assisting the laid off workers in talks with Deloitte.

When ELE recruits its workers, they work for various construction, logistics, and healthcare firms, which are called their “economic employers.”

There is no employer-employee relationship between the ELE workers and their economic employers, Maga said. Nelson also said that the contracts he had were only with ELE.

“We were only supplied to the companies. So we could be pulled out any time. But it also depends on if the company likes us, so they can absorb us and take us from ELE,” Nelson said in Filipino.

If what Nelson described sounds familiar, it should very well be. His situation, as well as those of the rest of the ELE workers, mirrors contractualization as we know it in the Philippines. Labor contracting agencies in the Philippines employ workers who are contracted out to clients for a period of usually not more than six months. One can usually find them in security, maintenance, and food service jobs.

This practice is also known here in the Philippines as “endo,” a play on the phrase “end of contract.” Because their jobs last only until the end of their contracts, there is no security of tenure nor benefits. Exploitative companies hire these fixed-term employees and continuously renew their contracts to avoid giving the benefits that a regular worker is lawfully entitled to.

Time and again, various administrations have tried to end the practice of “endo” in the Philippines. In both chambers of the current 19th Congress, bills looking to end abusive forms of contractualization and strengthen workers’ rights to security of tenure stagnate at the committee level.

According to Maga, labor-hire companies in New Zealand can have even “worse” operations than the months-long contracts that are common in the Philippines, because they employ workers for periods of two months, or even just two days.

Receivership explained

In an interview with Rappler on Tuesday, January 30, David Webb, one of ELE’s receivers from Deloitte, said that the company went into receivership because it had “run out of cash.”

Webb said that as ELE lost business over months, the company reached out to several parties in a bid to acquire funding, and explored the possibility of selling the company. But both of these attempts were unsuccessful, leading the company to request that a receiver be appointed.

Webb and Robert Campbell were asked to be receivers of the company just days before it shut down. They were appointed as receivers in the morning of December 20, the same day the workers were told that the company was folding.

As receivers, Webb and Campbell assess whether the business can continue to trade. They look for opportunities to sell the business, and in the event they are unable to, they strive to dispose of the assets and distribute monies in accordance with New Zealand law.

As a labor-hire company, ELE’s main assets were its workforce. Since the company could no longer pay them, the receivers needed to terminate their employment and get final payments from ELE’s clients, or the economic employers.

Webb said that while it was technically possible for the company to bounce back and rehire, it was unlikely, since its former workers had already begun seeking new employment.

“What it would take for that to occur would be for the receiver to have paid back all of the debts so that the company had returned to solvency, and then the company would then be returned to the director at that point for them to continue to trade… Whilst that is technically possible, it is highly unlikely in this situation, given the workforce that’s moved on and also the level of the debts that [the] ELE Group [has],” said Webb.

Webb explained that the collection of the final pay from ELE’s clients was “slower than [they] would have hoped” due to the holidays. Maga also explained that New Zealand was a “laid-back” country that took holidays seriously. Webb said that ELE’s clients were only starting to come back to work in the recent days.

In one to two days, Deloitte expects to inform the workers of the respective final payments owed to them. Payments may be released after that, though Webb said the timeframe had yet to be finalized.

Attractive working conditions, despite job insecurity

According to Maga, FIRST Union observed that ELE Group paid its workers relatively well compared to other labor-hire companies. Some workers earned NZD$36 an hour – and if one were to multiply that with eight hours a day for five days a week, the total would be $1,440 in a week, or around P49,810.

“Kaya ang dami talaga na gusto lumipad sa kanila (That’s why many workers really want to go abroad for them),” said Maga.

Many Filipinos want the work, and the feeling is mutual with construction recruiters. Maga said that Filipino workers are in demand because they “speak English well, work quickly, and learn quickly.”

Maga said that ELE recruited many Filipino workers because of the good business they gave – what he called the “labor-hire scheme.” The workers whom the union is assisting were offered 30 hours of guaranteed work. If a worker’s given salary was $27 an hour, Maga explained, labor-hire companies could charge their economic employers $55 an hour, which would give them a $28-profit margin.

“Kaya isang magandang negosyo din sa kanila ‘yan. Kaya gustong-gusto nila mga Pilipino dahil sa ganyang scheme (That’s why it was so profitable for them. They wanted Filipinos so much because of that scheme),” he said.

According to industry research firm IBISWorld, there are over 1,000 labor-hire companies in New Zealand as of 2024.

Webb said that ELE belonged to a small group of struggling labor-hire companies, but the industry was mostly afloat and continued to grow.

“Even if a labor-hire company says they can no longer employ you, OFWs have the option to find new jobs to keep their work continuous. That’s the advantage of the many Filipino workers, because the labor market is in their favor,” said Maga in a mix of English and Filipino.

As of writing, Nelson has been able to find new work. Apart from the community support over the past weeks, he and some others were able to get by with financial assistance that the Philippine Department of Migrant Workers gave them on January 16.

Longer tenure: A win for employee and employer

According to Maga, while a business can potentially save from the non-renewal of contract workers, they can also lose productivity by letting go of experienced workers.

“That’s why some employers who recruit OFWs are proposing that they be given work visas with longer validities. Not just one year, two years, or three years – they want it at five years. And the good thing about New Zealand is that the government listens,” Maga said, adding that policymakers were aware of the six-month contractualization practice in the Philippines.

Maga also said that many Filipinos in New Zealand were “sick and tired” of contractualization, which is what led them to go abroad. For Nelson, it was both the job insecurity and the low salaries that pushed him to seek better opportunities abroad.

“Kung magkakaroon man tayo ng trabaho sa Pilipinas, sana baguhin nila ‘yung law o ‘yung batas na six months contract. Kung hanggang maaari, mas pahabain pa po sana nila para hindi na po mahirapan ‘yung mga kababayan natin na maghanap ulit ng panibagong trabaho,” said Nelson.

(If we were to have jobs in the Philippines again, I hope they change the law to prevent six-month contracts. They should make it longer so that workers like us don’t have to deal with the difficulty of finding new jobs.) – Rappler.com

NZD$1 = P34.59

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Unpaid care work by women is a public concern](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240725-unpaid-care-work-public-concern.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.