SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

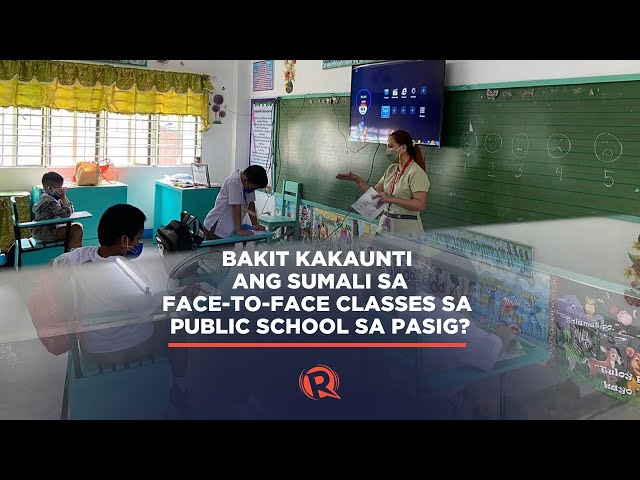

MANILA, Philippines – It was 4:30 am of November 15, and seven-year-old Issa Bautista was already awake and busy preparing for her classes that would start at 7. This time around, it wasn’t a modular class at home nor an online one. Her school, Longos Elementary School in Alaminos City, Pangasinan, was chosen as one of the 100 public schools in the country that would start limited face-to-face classes for a pilot run.

“Nakaligo na si Issa. Nakapag-prepare na rin ako ng pagkain niya, ‘tsaka mga sapatos niya, prepared na para sa kanyang pagpasok. Uniforms, excited po siya talaga maisuot ‘yun para makabalik at makapag-aral na sa school,” Issa’s mother, Christabel, told Rappler.

(She already took a bath. I have prepared her food, and the shoes she would wear for school. She’s also excited to wear her school uniform, to return to school and study there.)

Christabel was one of the struggling parents of students at Longos Elementary School who was excited about the resumption of face-to-face classes. For one whole school year, she was among the many Filipino parents who bore the brunt of the distance learning setup for which the country’s school system was unprepared . (READ: Parents bear the brunt of distance learning as classes shift online)

“Matagal na naming sinasabi na mga magulang na sana bumalik na sila sa school, magkaroon ng face-to-face. Ito talaga ang wish namin. Sinasabi namin sa mga teachers namin na sana, ’Ma’am, magkaroon na ng face-to-face kasi iba po ‘yung kayo ang nagtuturo eh,'” Christabel said.

(We, parents, have been wishing for schools to open, to have face-to-face classes. This is really our wish. We had been telling their teachers, “Ma’am, we hope that face-to-face classes resume because you can teach better than we do.”)

The Philippines, one of the most virus-hit countries in Asia, was the last country in the world to reopen schools for in-person classes since the World Health Organization declared a pandemic in March 2020.

While Issa and thousands of other students felt some sense of normalcy during the start of in-person classes, this was not the case for millions of other students. As of December 2021, there were only 287 public and private schools joining the pilot run of in-person classes. This was just a fraction of some 60,000 primary and secondary schools in the country.

As the Philippines and the rest of the world were just recovering from the surge in infections driven by the Delta variant, they faced yet another, more transmissible, variant called Omicron, which is sweeping across the globe and driving surge in infections in several countries.

On January 2, the Department of Education (DepEd) announced that it was halting the expansion phase of the limited face-to-face classes in the country which was supposed to start on the first week of 2022. The agency also announced the suspension of in-person classes in areas under Alert Level 3, including Metro Manila and three provinces around it.

‘Failed’ pandemic response

For many, the long school closure could have been prevented if only the government had managed the pandemic better. For critics, the prolonged school closure in the country reflected misplaced priorities and failed management of the health crisis.

Regina Sibal, lead convenor of education advocacy group Aral Pilipinas, said that, aside from the failed pandemic response, the government’s “blanket policy” was another barrier to the reopening of schools.

“The difficulty is in the single-policy approach. It may be really good to localize certain things in terms of decision making. It’s not only the DepEd that will support the opening of schools but the local government units,” she said.

The long overdue return of students to in-person classes once again suffered a major setback. With the ever-mutating novel coronavirus, how can the Philippines prepare its schools for the possible dangers of virus mutations and future health crises?

What the government can do

At the Senate basic education panel’s hearing on the implementation of limited face-to-face classes on December 17, Senator Pia Cayetano asked DepEd what should be done to prepare schools for future health crisis to avoid prolonged school closure.

“We cannot always just keep shutting down all schools. The likelihood of another pandemic, another worldwide health scare, is very likely. We just have to really learn how live with [the virus],” she said.

Rappler spoke with Aral Pilipinas and Teachers’ Dignity Coalition to discuss how the Philippines could pandemic-proof its schools. Below are their recommendations.

- Integrate or strengthen health crisis education in the curriculum

One of the main observations during the first week of face-to-face classes in select schools was that young students tended to take off their masks while inside the classroom. Most of students also disregarded basic health protocols, such as observing physical distancing and limiting interactions with their peers, due to lack of knowledge about the importance of these protocols.

Face masks have become essential in surviving a pandemic. For more vulnerable groups, the right face mask could spell the difference between life and death. The government has since required the public to wear face masks, especially when outside their homes.

Sibal said that the coronavirus pandemic is the perfect time for education leaders to “institutionalize” health crisis education. While maintaining proper hygiene is already integrated in subjects in schools, it is not enough to give students an understanding of the gravity of global health crises.

“Let’s look at what our [current] curriculum is and how it’s being delivered so that we can really provide our students with the foundation skills that they need. It’s included in K-12 program that we have to be at par with other countries,” she said.

At a Senate hearing on December 17, Education Assistant Secretary Malcolm Garma said that even DepEd recognizes that the COVID-19 health crisis could not be the last pandemic. He said that DepEd aspires to integrate in the student’s learning the importance of observing health protocols, but he didn’t give on details how the agency would go about it.

“It’s only in schools that we get to teach the students the importance of wearing face masks and following the signages and observing protocols. This is what really we aspire for – that children become conscious of these protocols,” Garma said.

- Reduce class size, build more classrooms

Teachers’ Dignity Coalition chairperson Benjo Basas stressed the need for the country to build more classrooms so schools could reduce their class size.

Classroom shortages had been a problem even before the pandemic. In some schools, 75 to 80 students were packed into one classroom meant for only 40. To make up for the lack of classrooms, class shifting had been implemented to accommodate enrollees every year. (READ: Classroom shortages greet teachers, students in opening of classes)

While situation in classrooms for the school year 2019-2020 improved, the number of classrooms is still inadequate for the current policy of using classrooms at limited capacity during face-to-face classes. For instance, elementary schools had an average class size of 29, junior high schools at 39, and senior high schools at 31. (READ: What we know so far: Pilot run of limited face-to-face classes in PH)

Based on the guidelines of the DepEd and Department of Health, a classroom could only accommodate 16 students at a time to avoid crowding. But with the classroom-student ratio for SY 2019-2020, it is clear more classrooms are needed.

But Sibal stressed that, more than building classrooms, the government should also be considering the layout and design of school buildings so that these would allow for proper air flow and ventilation.

- Hire teachers, teaching-aides, and school nurses

The classroom shortage goes with the need to hire more teachers, Basas said. “We should also hire more teachers so they won’t have extra workload. And, of course, just like in other countries, we should also have teaching aides that would assess our teachers,” he said in Filipino.

Data from the DepEd also showed that there were only 3,657 public school nurses for 21,741,049 public school students in 2019. This means a school nurse would have to attend to an average of 5,945 students. (READ: Are PH schools ready for face-to-face classes during pandemic?)

This would pose a problem since immediate attention is needed when a student figures in an emergency related to the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, the novel coronavirus has infected over 2.8 million people in the country.

- Build clinics, hand washing facilities

The problem in terms of facilities goes beyond inadequate classrooms. Only 13,081 of some 47,000 public schools have school clinics. In terms of basic hand washing facilities, only 44,043 schools have access to them.

- Address technology problem, digital gap

The pandemic highlighted the digital divide between rich and poor students. A number of students could not access online lessons due to lack of gadgets and internet connectivity.

Basas said that the government should be working on how they could provide technology access to struggling learners, especially since the new normal in education would be a combination of remote learning and limited in-person instructions.

“Of course, we need the technology. If we all go back to schools, that would not mean it’s full face-to-face, it would also be technology-based. We need infrastructure and electricity in all areas. We need internet and connectivity in all schools and communities. We need to help the poor families,” he said in Filipino.

The DepEd has expressed optimism that all schools in the country will eventually transition to limited face-to-face classes in school year 2022-2023. But with the looming threat of Omicron, uncertainty remains.

While many parents believe that there’s no better alternative to traditional face-to-face classes, they would only allow their children to attend school if it’s already safe out there and systems for their safety are already in place.

For Christabel, it would be a great frustration if Issa’s school in Pangasinan would be shut down again in case another surge in infections happens in their area. She only wants the best education for her child, and she thinks distance learning cannot provide that.

“Pangarap namin na mabigyan siya ng tamang edukasyon, makatapos siya ng college. Kasi ‘yun lang ang tanging maipapamana namin sa kanya. Wala kaming lupa, wala kaming kayamanan, kaya ‘yun po lamang ang puwede naming maibigay,” Christabel said.

(Our dream for her is to have quality education. We want her to finish college. Because that’s the only thing we could leave behind for her. We don’t have our own land, we’re not rich, that’s why education is the only thing we can give her.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.