SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This reporting tour of Ukraine was conducted upon the invitation and with the support of the Ukraine Crisis Media Center, a non-government organization based in Kyiv, with assistance from the Indonesian Association for Media Development, an NGO based in Jakarta.

First of 2 parts

I understood what it means to live in Ukraine at war when I retired to my hotel room in Warsaw at 2:08 am on Wednesday, February 28, 2024, after traveling 19-and-a-half hours by land from Kyiv.

My lights were out but the amber glow from street lamps peeked through the window. The windows on the hotel’s opposite wing were all dark. Everyone must’ve been asleep.

I had been traveling since 5:30 am the previous day: from Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, through Lviv, Ukraine’s western gateway, to Warsaw, the capital of Poland. The queue at the border checkpoint took five hours. By the time I and the six other journalists on this reporting tour checked in at our hotel in Old Town Warsaw, we were half asleep and barely had the energy to bid one another good night.

It was a business hotel; the rooms were straightforward. Poland is in the Schengen Area, in the European Union, both of which exclude Ukraine. For less the price, we got cushier rooms in Lviv, Kyiv, and Chernihiv. But as I lay down in this very basic hotel room in Old Town Warsaw, I felt my mind and body relax to a degree that I realized I had not been able to the whole time we were in Ukraine.

Here, at last, I could sleep without my phone near my ear. No air raid alert would ring in the middle of the night and order me to rise from bed and run to a bunker. Poland is not a war zone. No Russian missiles criss-cross the Polish airspace. Only the moon and the stars traverse the sky here.

And then my thoughts drifted to the friends we had made and who remained in Ukraine – their names are Myra, Yulia, and Serhii – and I wondered when the last time was that they relaxed like this. I imagined them tucking in, in their homes in Kyiv, trying to sleep in the artificial silence provided by Ukraine’s Patriot system intercepting Russian missiles, their phones close at hand so they wouldn’t sleep through an alert, in case of an attack.

When our hosts decided not to take our group to the war front, I worried there wouldn’t be stories worth telling from this reporting tour of Ukraine. Wasn’t the important story the story of the horrors on the frontline? Weren’t the worst and therefore most noteworthy impacts of Russian aggression to be found where the war was at its bitterest and most vivid? What was the point in reporting from parts where people seemed to carry on normally? Wouldn’t that beat around the bush?

Lying in bed, staring at the empty sky through the window of my room in Warsaw, I realized that nothing in Ukraine is or will be normal for as long as it is at war with Russia, and very few of us know what private sufferings its people endure and will have to endure in the meantime.

Carnage, the story we often expect to come out of war zones, is a story already well told. The Associated Press documentary 20 Days in Mariupol almost chokes on itself reporting Russia’s atrocities in as much detail as video allows. It succeeds in its aim to be compelling, so much that it recently won an Oscar. But it seems no Oscar could rally the world to compel Russia to leave Ukraine alone.

Mstyslav Chernov, the journalist and filmmaker behind 20 Days in Mariupol, risked dying while trying to get his footage out of the war zone to be seen by the world, yet he doubted it would be worth the sacrifice. “How could more death change anything?” he asks in the documentary.

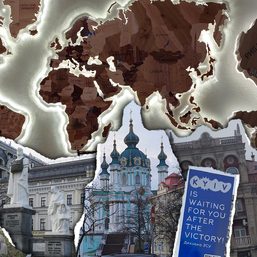

This story, then – my report from an eight-day journey through Ukraine – isn’t about death and destruction, although their mention is inevitable. It’s a story that has Vladimir Putin’s face printed on toilet paper and condom packets for sale in the streets of Kyiv and Lviv. It sees Ukrainians bearing up under the worst inhumanities they’ve been subjected to by Russia. It notes the cheerful blue tourist totems standing on Kyiv’s every corner, saying, “Kyiv is waiting for you after the victory!”

This, though, is not a story of hope, because the situation is dire and already out of hand. This journey through Ukraine’s battle scars is a cautionary tale, a warning of an impending global apocalypse that hinges on whether or not Russia will have its way.

No supernatural voice

I know the smell of a burnt house because my family’s house once caught fire in December 2002. I mention this because I recognized the smell when we arrived in Borodyanka, one of the towns surrounding Kyiv where Russian forces unleashed hell in early March 2022, during their campaign to take the capital – and all of Ukraine with it – that began on February 24, 2022.

The soot everywhere, the craters on the ground, apartments sliced in half, the jagged outlines of shelled condominiums testify to the horrors that happened here. But the noxious smell of singed living quarters, still strong in the freezing air two winters since the attack, makes it real to the visitor. The invaders were here. People were brutalized, dehumanized, and murdered here. This is hell on earth; fire from the Russian army scorched everything.

Natalia Buzovetska witnessed all of it. She looked put-together in her white parka and taupe beanie as she walked us, a group of seven Asian journalists, through the abandoned complex. She wept as she recounted the Russian soldiers advancing to her neighborhood, shooting indiscriminately at people as bombs fell on their homes.

“They could see that we were a residential area but they attacked us anyway,” Natalia said. She spoke in Ukrainian; Yulia Volfovska from our host, the NGO Ukraine Crisis Media Center, translated into English.

“Nothing here could have made them think we were the military or that this was a military camp.”

I imagine how it must have felt to see platoons of foreign soldiers marching towards you, sweeping the air with their rifles, sending bullets in all directions. Bombs falling from the sky. That building hit, then another, then yours. Everything is burning. Your neighbors panic; their screams make your skin crawl, like you’re about to pee through your pores. They run for cover; they run every which way. Bullets hit them. Things worse than bullets hit them. You see people you know die. Their blood spurting. Their body parts severed. You wonder what you or your compatriots have done to elicit such hatred from another country.

In training to survive hostile environments, journalists are taught, when there are bullets flying, to get as low on the ground as possible and crawl until it’s safe enough to get up and run; find a wall to put between themselves and the source of the gunfire, if they’re able to tell where it’s coming from. When there’s too little time to run from a grenade: fall to the ground face down, the head away from the explosive and the feet, together, towards it, so the shrapnel hits the soles and not any softer, more vital part of the body.

Would I have remembered all these if I were in Borodyanka that day of the attack? I wonder. Could I have made sensible choices, taken sensible action? Or would shock have messed with my bearings such that I would have failed to survive? Wouldn’t a divine voice have activated in my head and supernaturally directed me step by step so I wouldn’t die in the chaos? Surely, if not God, then my subconscious would have reminded me of what I was taught, no?

But how many of the people in Borodyanka were trained for hostile environments? Natalia saw her neighbors die. One after the other. From bullets. From bombs. From chunks of their own homes crashing. They didn’t find a way to save themselves. No voice told them where to go or what to do.

The condominium complex in Borodyanka now rests in perpetual silence. Its residents have either been killed or have fled. They were just ordinary people going through their day.

‘No logic to Russia’s actions’

Ukraine’s territorial defense forces are a reserve unit of the military whose primary task is to defend their own locale. In Moshchun, a quiet town near Kyiv, the territorial defense forces made a ferocious stand against the invading Russian troops in March 2022, and many of their neighbors stayed with them as they fought.

Their objective was to defend the town, but when that was lost, the objective became to stop the Russians from advancing further to Kyiv. Because if the capital falls, then all of Ukraine falls.

The Moshchun defenders knew they were the final wall between the invaders and their main target. They knew it had to end with them.

The neighbors didn’t flee, because they wanted to cook food for the fighters who were their sons, daughters, fathers, brothers, sisters, friends, childhood buddies. Locals told of one grandmother who would walk through the crossfire carrying a pot of soup or a basket of bread for the defenders. Others gathered warm clothes and sewed tents. It was winter; the cold in the battlefield was brutal.

In Moshchun today, war-damaged houses that could be repaired have been repaired; the only visible remnants of the fighting are the houses damaged beyond repair, which you find every few blocks. Those, and a patch of forest beside the road. Here, portraits hang on the trunks of trees, surrounded by the Ukrainian colors fluttering in the wind.

A trench hems the far end of this patch of forest where the trees are sparse; it is almost a clearing. This was the trench from which the territorial defense forces fired at the Russian troops marching on the road to Kyiv. Now the trees bear images of the dead defenders’ faces. They were photographed in their uniforms, smiling. It’s winter and everything looked gray, but the smiles in these photos were bright, and fresh flowers in cheerful colors adorned these memorials, disrupting the overall gloom.

Now, Moshchun is quiet again. The village defenders, with reinforcements from other military units, expelled the Russians before the month was out. They never reached Kyiv.

But 118 of the Ukrainian defenders were killed in battle. It was a win, but then it wasn’t.

“What is the main message? Never try to find some logic in actions of Russians. Unfortunately,” said Iryna Kabalska, who leads reconstruction efforts in Moshchun. She shook her head, threw her palms in the air in incredulity. “Because the idea is mass destruction. It’s not about some changes or some threats or something like this. Because this village is not threatening Russia with NATO bases. As well as Ukraine, all Ukraine.”

Except that there is a logic behind the Russian military’s actions. It’s a perverse logic, one that makes sense to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Putin condoms and toilet paper

The Dnipro Hotel in central Kyiv is a muscular hulk of a building: stone surface, all straight lines, dark wood interior. Megalithic, pragmatic, promising no warmth. A brutalist souvenir from Ukraine’s Soviet past.

This was home to us, seven journalists from South and Southeast Asia, while we were in the Ukrainian capital. Across a roundabout from the Dnipro Hotel is the Ukrainian House, another brutalist behemoth that used to be a museum to Lenin. It’s now a convention center that houses the office of the Ukraine Crisis Media Center, our host and sponsor on this reporting tour.

This Soviet showcase is just one part of Kyiv. A short, rather steep uphill walk on the lane past the Ukrainian House leads to St. Michael’s Square. It gets its name from the magnificent cathedral and monastery complex with golden onion-shaped domes that crown this hill. It’s the focal point of Old Kyiv, the city’s historic nucleus, some of whose features date back a millennium.

Here, you can stand at a corner, and the view is as it has been for literal ages. Churches, apartments, universities, theaters, even lighting fixtures are nostalgic. Domes, spires, steeples, arches, and cupolas upstage the communist-era monoliths. They speak of the primordial Ukraine that existed before Russia’s impositions.

It could be because they knew they were speaking to foreign journalists, but the guides who toured us around the old quarters of Kyiv, Lviv, and Chernihiv seemed to frame their spiels as arguments for Ukraine’s existence: This church was built in the 1100s; this monument honors a Romantic poet; this wall formed part of the rampart that defined the city’s limits a thousand years ago – see, we’ve been a country for a long, long time. We deserve to exist.

This defensive tone speaks to Russian disinformation that claims Ukrainians are actually just Russians with a fancy name and make-believe identity – a pretext for their annihilation and annexation.

“That concept needs to disappear forever,” Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, said in a March 4 speech. He was referring to Ukraine’s assertion of an identity separate from Russia’s.

“Ukraine is definitely Russia,” Medvedev continued, to the Russian audience’s applause.

Putin has said several times that “Ukraine doesn’t exist.” He said Russia has a legitimate historic claim over Ukraine, or at least parts of it. He said Ukraine needs to be “denazified.” He said Ukraine staged the massacres in Bucha and Mariupol and everywhere else, and the casualties seen in videos were actors.

Ukrainians don’t buy any of this. “It is the rave of a madman,” said Serhii Uzlov, a tour guide in Kyiv.

Russia’s disinformation may fool people around the world, but not in Ukraine, where people are well-versed in their history.

If anything, the full-scale invasion that started in February 2022 has made Ukrainians want to be anything but Russian. The mass destruction of their eastern regions, the constant aerial bombardment, the incalculable loss of human lives, and Putin’s barefaced denial of these blatant atrocities have made him and Russia loathsome to Ukrainians.

At a refugee shelter in Lviv, Ukraine’s westernmost major city farthest from the Russian-occupied eastern regions, a group of women who’ve escaped the fighting came to us when they learned we are journalists. One grandmother let out a stream of invectives aimed at Putin. She wanted to register her contempt for the man. She said she will never give up being Ukrainian because it’s the biggest “up-yours” to Putin – that she would rather live the rest of her days in refugee housing than back home under Russian rule.

At a street bazaar in Lviv, a stall sold doormats with print that said, in Ukrainian, “Wipe your feet.” Replacing one of the letters in the word for “feet” was the face of Vladimir Putin. I told Myra – Myroslava Iaremkiv, donor relations manager of UCMC and our chaperone for most of the tour – that I wanted to buy a few of the doormats as souvenirs. I thought it made the perfect pasalubong from Ukraine. She told me to hold off – the toilet paper rolls are cheaper, and we’re sure to find some if not in Lviv, then in Kyiv.

True enough, days later in Kyiv, at one of the shops along the pedestrian underpass connecting the Dnipro Hotel to the Ukrainian House, we found a stack of toilet paper rolls with Putin’s face printed on every sheet, with Cyrillic letters that I didn’t understand. Myra told me the letters were the initials to “Fuck you, Putin.”

Besides the Putin tissues and doormats, the store also sold condoms in packets with Putin’s face drawn where the glans of a penis would be. Other packets featured a Putin caricature with dog ears, chained and on all fours, emblazoned over a rolled condom.

How rich, no? This is exactly the kind of freedom Ukrainians know they will lose if they fall to Russia: to have a mind of their own and the right to speak it.

‘Then let the baby die’

The Russian soldiers didn’t know what a microwave oven was. Because it was a metal box with push buttons, they thought it was a safe. And yet they fancied themselves the saviors of Ukrainians, come to rescue them from scarcity if they would bow to Moscow’s power.

That’s what they told the 368 hostages they kept with scant food and water, without electricity and ventilation, in the 190-square-meter basement of a schoolhouse in Yahidne, a town near the Russian and Belarusian borders, for 27 days in March 2022.

The survivors included Ivan Polhuy, the school’s former janitor. Two years later, he ushered us into the basement that served as a dungeon for him, his wife, children, grandchildren, and their entire village. Russian troops used them as human shields against the Ukrainian army.

“When they saw our lightbulb, they asked where our generator was. The concept of centralized electricity is alien to them,” Ivan told us in Ukrainian, with Yulia translating.

To Ivan, it was proof that those Russian soldiers lived poor, primitive lives wherever it was in Russia they came from. I suspect it could be the result of disinformation: the Russian government wants its citizens to believe Ukraine is backward and dysfunctional, and Russia does it a favor by occupying it.

But then again, the Russian soldiers didn’t know what the microwave was for.

Even now that it’s empty, the basement is an oppressive place. A hallway little more than shoulder width connects several rooms of varying sizes. Bare walls and floors. No windows or air shafts.

Imagine an entire village cramped here. Less than half a square meter for each person. No daylight, no idea whether it’s day or night. The villagers rationed what they found in the school’s pantry – cabbage, potatoes, some water. Two people had to last each day sharing a cup of whatever food there was.

It was winter but a week into their captivity, the air in the basement became so stiflingly hot and humid, the vapors from the people condensed on the ceiling and dripped back to them. Men, women, and children used the same few buckets as toilets. They confined these buckets of their excrement to a corner, but of course not the stench.

But that wasn’t the worst they had to deal with.

“Before they died, people lost their mind,” Ivan told us.

That people would die was inevitable. The youngest hostage was a 6-week-old baby and the oldest, a 93-year-old grandmother. When one of the babies became ill, a few adults pleaded with the Russian soldiers for help – the unit that held them included medics.

The soldiers, according to Ivan, replied: “Then let the baby die. What can we do? This is war.”

They refused to save the child.

“They had a medical station here but they did not provide any medical assistance to the villagers.”

The captive children drew on the walls. They fantasized about escape routes and football matches even as they depicted some of the most horrific moments of their living entombment: Russian soldiers shooting people lined up at the outdoor toilet (why they resigned themselves to urinating and defecating into buckets); planes dropping rockets overhead (the one good thing about being in the basement is the relative safety from air raids); an explosion that sounded frighteningly near.

On a wall where the adults etched a calendar and a tally of the dead, the children carved the words to Ukraine’s national anthem.

This is the nation Putin says does not exist. – Rappler.com

Part 2 | What if Russia wins? What the Ukraine war means for Filipinos

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Expectations for Philippines-US-Japan trilateral cooperation: A view from Japan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-ph-usa-jp-cooperation.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=447px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Rappler’s Best] Of wars and presidents](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/volodymyr-zelenskyy-ukraine-president-marcos-bilateral-meeting-reuters-june-3-2024-004-scaled.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=445px%2C0px%2C1703px%2C1703px)

![[OPINION] Unjust wars and a just peace](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-unjust-war-just-peace03262024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.